(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, D.C. - Alaska's melting glaciers are adding enough water to the Earth's oceans to cover the state of Alaska with a 1-foot thick layer of water every seven years, a new study shows.

The study found that climate-related melting is the primary control on mountain glacier loss. Glacier loss from Alaska is unlikely to slow down, and this will be a major driver of global sea level change in the coming decades, according to the study's authors.

"The Alaska region has long been considered a primary player in the global sea level budget, but the exact details on the drivers and mechanisms of Alaska glacier change have been stubbornly elusive," said Chris Larsen, a research associate professor with the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Larsen is lead author of the new study accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

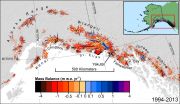

The UAF and U.S. Geological Survey research team analyzed surveys of 116 glaciers in the Alaska region across 19 years to estimate ice loss from melting and iceberg calving. The team collected airborne lidar altimetry data as part of NASA's Operation IceBridge and integrated the new data with information from the 1990s collected by UAF scientist and pilot Keith Echelmeyer.

They combined the lidar observations with a new mountain glacier inventory that characterizes the size and shape of every glacier in the Alaska region, which includes the glaciers of Alaska, southwest Yukon Territory and coastal northern British Columbia.

"This large dataset of direct observations enabled a much more detailed assessment and attribution of recent glacier change than previously possible," Larsen said.

Mountain glaciers hold less than 1 percent of the Earth's glacial ice volume. The rest is held in ice sheets on Antarctica and Greenland. However, the rapid shrinking of mountain glaciers causes nearly one-third of current sea level rise, previous research has shown.

"Alaska has been identified for years as a big contributor in global sea level rise, but until now we have not had a clear understanding of the processes responsible for the rapid changes of these glaciers," said Shad O'Neel, a co-author of the new paper and geophysicist with the USGS Alaska Science Center in Anchorage.

The study used the airborne observations to compare the changes of two main types of glaciers: those that end on the land, and those that end in lakes or the ocean, referred to as calving glaciers. Any glacier can lose mass through surface melting, but only those ending in water can lose ice through iceberg calving.

"We've long wondered what the contribution of iceberg calving could be across the entire state," O'Neel said. He noted that Columbia Glacier in Prince William Sound has retreated more than 19 kilometers (12 miles) mostly because of iceberg calving and thinned by more than 450 vertical meters (1,500 vertical feet) since 1980.

Using the newly enabled ability to separate glaciers into different categories using the lidar data, the researchers made some surprising discoveries.

"Our results show the regional contribution of tidewater glaciers to sea level rise to be almost negligible," Larsen said. Tidewater glaciers are glaciers that end in the ocean. "Instead, we show that glaciers ending on land are losing mass exceptionally fast, overshadowing mass changes due to iceberg calving, and making climate-related melting the primary control on mountain glacier mass loss."

"This work has important implications for global sea level projections. With improved understanding of the processes responsible for Alaska glacier changes, models of the future response of these glaciers to climate can be improved," Larsen said.

"Thinking about the future, it means that rates of loss from Alaska are unlikely to decline, since surface melt is the predominant driver, and summer temperatures are expected to continue to increase. There is a lot of momentum in the system, and Alaska will continue to be a major driver of global sea level change in upcoming decades," he added.

INFORMATION:

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 60,000 members in 139 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

The press release and accompanying images can be found at: http://news.agu.org/press-release/alaska-glaciers-make-large-contributions-to-global-sea-level-rise/

AGU Contact:

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

nbompey@agu.org

UAF Geophysical Institute:

Diana Campbell

+1 (907) 474-5229

dlcampbell@alaska.edu

Thanks to the extraordinary sensitivity of the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), astronomers have detected what they believe is the long-sought radio emission coming from a supermassive black hole at the center of one of our closest neighboring galaxies. Evidence for the black hole's existence previously came only from studies of stellar motions in the galaxy and from X-ray observations.

The galaxy, called Messier 32 (M32), is a satellite of the Andromeda Galaxy, our own Milky Way's giant neighbor. Unlike the Milky Way and Andromeda, which are star-forming spiral ...

The percentage of patients with early-stage breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving therapy increased from 54.3 percent in 1998 to 60.1 percent in 2011, although nonclinical factors including socioeconomic demographics, insurance and the distance patients must travel to treatment facilities persist as key barriers to the treatment, according to a report published online by JAMA Surgery.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a consensus statement in 1990 in support of this treatment method and that led to a substantial decline in rates of mastectomy and widespread ...

Sunscreen labels may still be confusing to consumers, with only 43 percent of those surveyed understanding the definition of the sun protection factor (SPF) value, according to the results of a small study published in a research letter online by JAMA Dermatology.

UV-A radiation is associated with skin aging, UV-B radiation is associated with sunburns, and exposure to both is a risk factor for skin cancer. In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced new regulations for sunscreen labels to emphasize protection against both UV-A and UV-B radiation, now known ...

The risk for tic disorders, including Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders, increased with the degree of genetic relatedness in a study of families in Sweden, according to an article published online by JAMA Psychiatry.

While tic disorders are thought to be strongly familial and heritable, precise estimates of familial risk and heritability are lacking, although gene-searching efforts are under way. Limitations also exist in previous research.

David Mataix-Cols, Ph.D., of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, and coauthors tried to overcome some of those limitations ...

Previous studies have led researchers to believe that individuals with social anxiety disorder/ social phobia have too low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin. A new study carried out at Uppsala University, however, shows that the situation is exactly the opposite. Individuals with social phobia make too much serotonin. The more serotonin they produce, the more anxious they are in social situations.

Many people feel anxious if they have to speak in front of an audience or socialise with others. If the anxiety becomes a disability, it may mean that the person suffers ...

WASHINGTON - The ongoing outbreak in the Republic of Korea (South Korea) is an important reminder that the Middle East respiratory virus (MERS-CoV) requires constant vigilance and could spread to other countries including the United States. However, MERS can be brought under control with effective public health strategies, say two Georgetown University public health experts.

In a JAMA Viewpoint published online June 17, Georgetown public health law professor Lawrence O. Gostin and infectious disease physician Daniel Lucey outline strategies for managing the outbreak, ...

Chicago, June 17, 2015 - Being the daddy isn't important for male gorillas when it comes to their relationships with the kids; it's their rank in the group that makes the difference, says new research published in Animal Behaviour. The authors of the study, from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) - now with Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago - the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International (Atlanta USA) and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany) say this supports the theory that for most of their evolution, gorillas lived in groups ...

A multi-institutional team of scientists has taken an important step in understanding where atoms are located on the surfaces of rough materials, information that could be very useful in diverse commercial applications, such as developing green energy and understanding how materials rust.

Researchers from Northwestern University, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of Melbourne, Australia, have developed a new imaging technique that uses atomic resolution secondary electron images in a quantitative way to determine ...

Reducing short breaks between shifts helps nurses recover from work, according to a new study from Finland. The study analysed the effects of longer rest and recovery periods between shifts on heart rate variability, which is an indicator of recovery.

Shift work can increase the risk of many diseases, for example cardiovascular diseases. The increased risk is partially caused by insufficient recovery from work, which interferes with the normal function of the autonomic nervous system regulating heart function and blood pressure, among other things. Nurses have too little ...

People make dramatically different decisions about who should receive hypothetical transplant organs depending on whether the potential recipients are presented as individuals or as part of a larger group, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The findings show that when recipients are considered in groups, people tend to allocate organs equally across the groups, ignoring information about the patients' chances of success.

"This is important because public policies about prioritizing resources ...