(Press-News.org) We can alter our facial features in ways that make us look more trustworthy, but don't have the same ability to appear more competent, a team of New York University psychology researchers has found.

The study, which appears in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, a SAGE journal, points to both the limits and potential we have in visually representing ourselves--from dating and career-networking sites to social media posts.

"Our findings show that facial cues conveying trustworthiness are malleable while facial cues conveying competence and ability are significantly less so," explains Jonathan Freeman, an assistant professor in NYU's Department of Psychology and the study's senior author. "The results suggest you can influence to an extent how trustworthy others perceive you to be in a facial photo, but perceptions of your competence or ability are considerably less able to be changed."

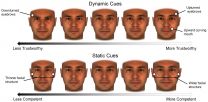

This distinction is due to the fact that judgments of trustworthiness are based on the face's dynamic musculature that can be slightly altered, with a neutral face resembling a happy expression likely to be seen as trustworthy and a neutral face resembling an angry expression likely to be seen as untrustworthy--even when faces aren't overtly smiling or angered. But perceptions of ability are drawn from a face's skeletal structure, which cannot be changed.

The study, whose other authors included Eric Hehman, an NYU post-doctoral researcher, and Jessica Flake, a doctoral candidate at the University of Connecticut, employed four experiments in which female and male subjects examined both photos and computer-generated images of adult males.

In the first, subjects looked at five distinct photos of 10 adult males of different ethnicities. Here, subjects' perceptions of trustworthiness of those pictured varied significantly, with happier-looking faces seen as more trustworthy and angrier-looking faces seen as more untrustworthy. However, the subjects' perceptions of ability, or competence, remained static--judgments were the same no matter which photo of the individual was being judged.

A second experiment replicated the first, but here, subjects evaluated 40 computer-generated faces that slowly evolved from "slightly happy" to "slightly angry," resulting in 20 different neutral instances of each individual face that slightly resembled a happy or angry expression. As with the first experiment, the subjects' perceptions of trustworthiness paralleled the emotion of the faces--the slightly happier the face appeared, the more likely he was seen to be trustworthy and vice versa for faces appearing slightly angrier. However, once again, perceptions of ability remained unchanged.

In the third experiment, the researchers implemented a real-world scenario. Here, subjects were shown an array of computer-generated faces and were asked one of two questions: which face they would choose to be their financial advisor (trustworthiness) and which they thought would be most likely to win a weightlifting competition (ability). Under this condition, the subjects were significantly more likely to choose as their financial advisor the faces resembling more positive, or happy, expressions. By contrast, emotional resemblance made no difference in subjects' selection of successful weightlifters; rather, they were more likely to choose faces with a particular form: those with a comparatively wider facial structure, which prior studies have associated with physical ability and testosterone.

In the fourth experiment, the researchers used a "reverse correlation" technique to uncover how subjects visually represent a trustworthy or competent face and how they visually represent the face of a trusted financial advisor or competent weightlifting champion. This technique allowed the researchers to determine which of all possible facial cues drive these distinct perceptions without specifying any cues in advance.

Here, resemblance to happy and angry expressions conveyed trustworthiness and was more prevalent in the faces of an imagined financial advisor while wider facial structure conveyed ability and was more prevalent in the faces of an imagined weightlifting champion.

These results confirmed the findings of the previous three experiments, further cementing the researchers' conclusion that perceptions of trustworthiness are malleable while those for competence or ability are immutable.

INFORMATION:

Want to lose abdominal fat, get smarter and live longer? New research led by USC's Valter Longo shows that periodically adopting a diet that mimics the effects of fasting may yield a wide range of health benefits.

In a new study, Longo and his colleagues show that cycles of a four-day low-calorie diet that mimics fasting (FMD) cut visceral belly fat and elevated the number of progenitor and stem cells in several organs of old mice -- including the brain, where it boosted neural regeneration and improved learning and memory.

The mouse tests were part of a three-tiered ...

Last June, in the early days of the Ebola outbreak in Western Africa, a team of researchers sequenced the genome of the deadly virus at unprecedented scale and speed. Their findings revealed a number of critical facts as the outbreak was unfolding, including that the virus was being transmitted only by person-to-person contact and that it was picking up new mutations through its many transmissions.

While public health officials now believe the worst of the epidemic is behind us, it is not yet over, and questions raised by the previous work still await answers.

To ...

PHILADELPHIA - Several well-known neurodegenerative diseases, such as Lou Gehrig's (ALS), Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's disease, all result in part from a defect in autophagy - one way a cell removes and recycles misfolded proteins and pathogens. In a paper published this week in Current Biology, postdoctoral fellow David Kast, PhD, and professor Roberto Dominguez, PhD, and three other colleagues from the Department of Physiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, show for the first time that the formation of ephemeral compartments ...

University of California San Francisco scientists have identified characteristics of a family of daughter cells, called MPPs, which are the first to arise from stem cells within bone marrow that generate the entire blood system. The researchers said the discovery raises the possibility that, by manipulating the fates of MPPs or parent stem cells, medical researchers could one day help overcome imbalances and deficiencies that can arise in the blood system due to aging or in patients with specific types of leukemia.

Similar imbalances can render patients vulnerable immediately ...

PORTLAND, Ore. -- Advancing the field of structural biology that underpins how things work in a cell, researchers have identified how proteins change their shape when performing specific functions. The study's fresh insights, published online in the journal Structure, provide a more complete picture of how proteins move, laying a foundation of understanding that will help determine the molecular causes of human disease and the development of more potent drug treatments.

Though it has long been recognized that proteins are not static, for more than 30 years, scientists' ...

The secret to preventing HIV infection lies within the human immune system, but the more-than-25-year search has so far failed to yield a vaccine capable of training the body to neutralize the ever-changing virus. New research from The Rockefeller University, and collaborating institutions, suggests no single shot will ever do the trick. Instead, the scientists find, a sequence of immunizations might be the most promising route to an HIV vaccine.

Scientists have thought for some time that multiple immunizations, each tailored to specific stages of the immune response, ...

BOSTON, June 18 -- An analysis of five families has revealed a previously unknown genetic immunodeficiency, says an international team led by researchers from Boston Children's Hospital. The condition, linked to mutations in a gene called DOCK2, deactivates many features of the immune system and leaves affected children open to a unique pattern of aggressive, potentially fatal infections early in life.

As the researchers -- led by Kerry Dobbs and Luigi Notarangelo, M.D., of Boston Children's Division of Allergy and Immunology -- reported today in the New England Journal ...

Musicians don't just hear in tune, they also see in tune.

That is the conclusion of the latest scientific experiment designed to puzzle out how the brain creates an apparently seamless view of the external world based on the information it receives from the eyes.

"Our brain is remarkably efficient at putting us in touch with objects and events in our visual environment, indeed so good that the process seems automatic and effortless. In fact, the brain is continually operating like a clever detective, using clues to figure out what in the world we are looking at. And ...

A trio of studies being published today in the journals Science and Cell describes advances toward the development of an HIV vaccine. The three study teams all demonstrated techniques for stimulating animal cells to produce antibodies that either could stop HIV from infecting human cells in the laboratory or had the potential to evolve into such antibodies. Each of the research teams received funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health.

In one study, published in Science, researchers demonstrate ...

CHAPEL HILL, NC - Before there were cells on Earth, simple, tiny catalysts most likely evolved the ability to speed up and synchronize the chemical reactions necessary for life to rise from the primordial soup. But what those catalysts were, how they appeared at the same time, and how they evolved into the two modern superfamilies of enzymes that translate our genetic code have not been understood.

In the Journal of Biological Chemistry, scientists from the UNC School of Medicine provide the first direct experimental evidence for how primordial proteins developed the ...