INFORMATION:

Other Harvard Chan School authors include Rays Jiang, Aziz Kosber, Markus Ganter, and Nicole Espy.

This study was supported by grants from NIH F32 AI093059, NIH F32 AI108251, American Cancer Society RSG-12-175-01-MPC, NIH R03 AI107475, NIH R21 AI099658, NIH R21 AI088314, and NIH R01 AI091787.

"Parasite calcineurin regulates host cell recognition and attachment by apicomplexans," Aditya S. Paul, Sudeshna Saha, Rays H.Y. Jiang, Bradley I. Coleman, Aziz L. Kosber, Chun-Ti Chen, Markus Ganter, Nicole Espy, Marc-Jan Gubbels, and Manoj T. Duraisingh, Cell Host & Microbe, online June 25, 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.06.003

Visit the Harvard Chan School website for the latest news, press releases, and multimedia offerings.

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health brings together dedicated experts from many disciplines to educate new generations of global health leaders and produce powerful ideas that improve the lives and health of people everywhere. As a community of leading scientists, educators, and students, we work together to take innovative ideas from the laboratory to people's lives--not only making scientific breakthroughs, but also working to change individual behaviors, public policies, and health care practices. Each year, more than 400 faculty members at Harvard Chan teach 1,000-plus full-time students from around the world and train thousands more through online and executive education courses. Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officers, the School is recognized as America's oldest professional training program in public health.

New target identified for inhibiting malaria parasite invasion

2015-06-25

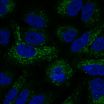

(Press-News.org) Boston, MA -- A new study led by researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health finds that a malaria parasite protein called calcineurin is essential for parasite invasion into red blood cells. Human calcineurin is already a proven target for drugs treating other illnesses including adult rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, and the new findings suggest that parasite calcineurin should be a focus for the development of new antimalarial drugs.

"Our study has great biological and medical significance, particularly in light of the huge disease burden of malaria," said senior author Manoj Duraisingh, John LaPorte Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases. "As drug resistance is a major problem for malaria control and eradication, it is critical that that we continue to develop new antimalarials that act against previously unexploited targets in the parasite to keep priming the drug pipeline."

The study appears online June 25, 2015 in Cell Host & Microbe.

The research team at Harvard Chan School used cutting edge genetic and cell biological methods to provide definitive evidence of the essentiality and function of calcineurin in parasite invasion. They found that the protein allows the malaria parasite to recognize and attach to the red blood cell surface. Parasites with inhibited calcineurin failed to invade and were not infective. Studies from a group at the University of Glasgow, which are published in the same issue of the journal, show the importance of calcineurin through different stages of the malaria life-cycle, implicating the protein as a potential target for blocking malaria transmission.

In addition to opening the door to potential new malaria treatments, these studies suggest that calcineurin could be targeted to treat other parasitic diseases. Researchers at Boston College working in collaboration with the Harvard Chan group showed that calcineurin is also important for cellular attachment by a related parasite that causes toxoplasmosis.

"Our study shows that the ability of malaria parasites to engage red blood cells is driven by an ancient mechanism for cellular attachment," said lead author Aditya Paul, a postdoctoral researcher at the Harvard Chan School. "In addition to a possible drug target, calcineurin underlies a very basic aspect of parasite biology."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New drug squashes cancer's last-ditch efforts to survive

2015-06-25

LA JOLLA--As a tumor grows, its cancerous cells ramp up an energy-harvesting process to support its hasty development. This process, called autophagy, is normally used by a cell to recycle damaged organelles and proteins, but is also co-opted by cancer cells to meet their increased energy and metabolic demands.

Salk Institute and Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) scientists have developed a drug that prevents this process from starting in cancer cells. Published June 25, 2015 in Molecular Cell, the new study identifies a small molecule drug that ...

Commenters exposed to prejudiced comments more likely to display prejudice themselves

2015-06-25

Washington, DC (June 25, 2015) - Comment sections on websites continue to be an environment for trolls to spew racist opinions. The impact of these hateful words shouldn't have an impact on how one views the news or others, but that may not be the case. A recent study published in the journal Human Communication Research, by researchers at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, found exposure to prejudiced online comments can increase people's own prejudice, and increase the likelihood that they leave prejudiced comments themselves.

Mark Hsueh, Kumar Yogeeswaran, ...

Children with severe head injuries are casualties of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

2015-06-25

June 25 -- During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. combat support hospitals treated at least 650 children with severe, combat-related head injuries, according to a special article in the July issue of Neurosurgery, official journal of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. The journal is published by Wolters Kluwer.

"Given the challenging environment and limited available resources, coalition forces were able to provide quality, timely, and life-saving care to many children" with severe head injuries, write Dr. Paul Klimo, Jr., of Semmes-Murphy Neurologic & Spine ...

Disconnect between doctors and patients on use of email and Facebook

2015-06-25

A large number of patients use online communication tools such as email and Facebook to engage with their physicians, despite recommendations from some hospitals and professional organizations that clinicians limit email contact with patients and avoid "friending" patients on social media, new research suggests.

The findings from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers suggest a disconnect between what patients expect and what physicians -- concerned about confidentiality and being overwhelmed in off-hours -- are willing to do when it comes to online ...

Study highlights 'important safety issue' with widely used MRI contrast agents

2015-06-25

June 25, 2015 - New results in animals highlight a major safety concern regarding a class of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents used in millions of patients each year, according to a paper published online by the journal Investigative Radiology. The journal is published by Wolters Kluwer.

The study adds to concerns that repeated use of specific "linear"-type gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) lead to deposits of the heavy-metal element gadolinium in the brain. The results will have a major impact on the multimillion-dollar market for MRI contrast agents, ...

Smartphone app may prevent dangerous freezing of gait in Parkinson's patients

2015-06-25

Many patients in the latter stage of Parkinson's disease are at high risk of dangerous, sometimes fatal, falls. One major reason is the disabling symptom referred to as Freezing of Gait (FoG) -- brief episodes of an inability to step forward that typically occurs during gait initiation or when turning while walking. Patients who experience FoG often lose their independence, which has a direct effect on their already degenerating quality of life. In the absence of effective pharmacological therapies for FoG, technology-based solutions to alleviate the symptom and prolong ...

Development of new blood vessels not essential to growth of lymph node metastases

2015-06-25

While the use of antiangiogenesis drugs that block the growth of new blood vessels can improve the treatment of some cancers, clinical trials of their ability to prevent the development of new metastases have failed. Now a study from the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center may have found at least one reason why. In their paper published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, an MGH research team reports finding that the growth of metastases in lymph nodes -- the most common site of cancer spread -- does not require new blood vessels but instead ...

Study finds a good appetizer could make your main course less enjoyable

2015-06-25

A good or mediocre appetizer has the potential to significantly change how the main course is enjoyed, according to one Drexel food science professor.

Jacob Lahne, PhD, an assistant professor in the Center for Hospitality and Sport Management, recently found that a comparatively good appetizer could make people enjoy the main course less than if it were preceded by a mediocre appetizer.

Lahne tested and analyzed subjects' hedonic (liking) responses to a main dish of "pasta aglio e olio" (pasta with garlic and oil) after they had either a good or mediocre bruschetta ...

Stanford researchers stretch a thin crystal to get better solar cells

2015-06-25

Nature loves crystals. Salt, snowflakes and quartz are three examples of crystals - materials characterized by the lattice-like arrangement of their atoms and molecules.

Industry loves crystals, too. Electronics are based on a special family of crystals known as semiconductors, most famously silicon.

To make semiconductors useful, engineers must tweak their crystalline lattice in subtle ways to start and stop the flow of electrons.

Semiconductor engineers must know precisely how much energy it takes to move electrons in a crystal lattice. This energy measure is the ...

New class of compounds shrinks pancreatic cancer tumours and prevents regrowth

2015-06-25

Scientists from UCL (University College London) have designed a chemical compound that has reduced the growth of pancreatic cancer tumours by 80 percent in treated mice.

The compound, called MM41, was designed to block faulty genes. It appears to do this by targeting little knots in their DNA, called quadruplexes, which are very different from normal DNA and which are especially found in faulty genes.

The findings, published in Nature Scientific Reports, showed that MM41 had a strong inhibiting effect on two genes -- k-RAS and BCL-2 -- both of which are found in the ...