(Press-News.org) MELBOURNE, FLA. -- A new study led by Florida Institute of Technology Professor Ningyu Liu has improved our understanding of a curious luminous phenomenon that happens 25 to 50 miles above thunderstorms.

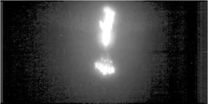

These spectacular phenomena, called sprites, are fireworks-like electrical discharges, sometimes preceded by halos of light, in earth's upper atmosphere. It has been long thought that atmospheric gravity waves play an important role in the initiation of sprites but no previous studies, until this team's recent findings, provided convincing arguments to support that idea.

The research, published in the June 29 issue of Nature Communications, includes comprehensive computer-simulation results from a novel sprite initiation model and dramatic images of a sprite event, and provides a clearer understanding of the atmospheric mechanisms that lead to sprite formation.

Understanding the conditions of sprite formation is important, in part, because they can interfere with or disrupt long-range communication signals by changing the electrical properties of the lower ionosphere.

Predicted by Nobel laureate C. T. R. Wilson in 1924 but not discovered until 1989, sprites are triggered by intense cloud-to-ground lightning strokes. They typically last a few to tens of milliseconds; they are bright enough to be seen with dark-adapted naked eyes at night; and only the most powerful lightning strokes can cause them.

The study, conducted by Liu, a Florida Tech professor of physics and space sciences, and collaborators Joseph Dwyer, a former professor at Florida Tech now at University of New Hampshire, Hans Stenbaek-Nielsen from University of Alaska Fairbanks, and Matthew McHarg from the United States Air Force Academy, investigated how sprites are initiated.

According to Liu, the perturbations in the upper atmosphere created by atmospheric gravity waves can grow in the electric field produced by lightning and eventually lead to sprites.

"Perturbations with small size and large amplitude are best for initiating sprites," Liu said. "If the size of the perturbation is too large, sprite initiation is impossible; if the magnitude of the perturbation is small, it requires a relatively long time for sprites to be initiated."

To validate their model, the team analyzed a sprite event captured simultaneously by high-speed, high-sensitivity cameras on two aircraft during an observation mission sponsored by the Japanese broadcasting corporation NHK. The high-speed images show that a relatively long-lasting sprite halo preceded the fast initiation of sprite elements, exactly as predicted by the model.

Hamid Rassoul, an atmospheric physicist and the dean of Florida Tech's College of Science, said the findings will be critical to future researchers.

"They will allow scientists to study not only sprites but also the mesospheric perturbations, which are difficult, if not impossible, to observe," he said.

Liu added, "Our findings also suggest that small, dim glows in the upper atmosphere may be frequently caused by intense lightning but elude the detection. There may be many interesting phenomena waiting for discovery with more sensitive imaging systems."

INFORMATION:

More on the study can be found at the Nature Communications website http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2015/150629/ncomms8540/full/ncomms8540.html.

NOTE: AVI video of a sprite is available upon request.

About Florida Institute of Technology

Founded at the dawn of the Space Race in 1958, Florida Tech is the only independent, technological university in the Southeast. PayScale.com ranks graduates' mid-career median salaries in first place among Florida's universities, and lists Florida Tech among the top 20 universities in the South--both public and private. Featured among the top 200 universities in the world according to Times Higher Education World University Rankings, the university has been named a Barron's Guide "Best Buy" in College Education, designated a Tier One Best National University in U.S. News & World Report, and is one of just nine schools in Florida lauded by the Fiske Guide to Colleges. The university offers undergraduate, master's and doctoral programs. Fields of study include science, engineering, aeronautics, business, humanities, mathematics, psychology, communication and education. Additional information is available online at http://www.fit.edu.

About Nature Communications

Nature Communications is an open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, physical, chemical and Earth sciences. Papers published by the journal represent important advances of significance to specialists within each field. The scope of the journal reflects Nature Publishing Group's core strength in the natural sciences, and includes areas in which Nature research journals serve to publish the most outstanding community-focused research papers. Find more information at http://www.nature.com/ncomms/index.html.

New research identifies the types of investors who are vigilant about corporate fraud, but finds that most of those investors are tracking the wrong red flags - meaning the warning signs they look for are clear only after it's too late to protect their investment. The work was performed by researchers at North Carolina State University, George Mason University, the University of Virginia and the University of Cincinnati.

"Individual investors get hurt if they own stock in fraudulent companies that cook the books, such as Enron," says Dr. Joe Brazel, a professor of accounting ...

This news release is available in Spanish. A technique to increase the flow of blood from the umbilical cord into the infant's circulatory system improves blood pressure and red blood cell levels in preterm infants delivered by Cesarean section, according to a study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

The study, published online in Pediatrics, was conducted by researchers at the Neonatal Research Institute at Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women and Newborns in San Diego, and Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, Calif. It was supported by NIH's Eunice Kennedy ...

Boston, MA -- Longer secondary schooling substantially reduces the risk of HIV infection--especially for girls--and could be a very cost-effective way to halt the spread of the virus, according to researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. In a study in Botswana, researchers found that, for each additional year of secondary school, students lowered their risk of HIV infection by 8 percentage points about a decade later, from 25% to about 17% infected.

"These findings confirm what has been fiercely debated for more than two decades--that secondary schooling ...

Longer secondary schooling substantially reduces the risk of contracting HIV, particularly for girls, according to new research from Botswana published in The Lancet Global Health journal. The researchers estimate that pupils who stayed in school for an extra year of secondary school had an 8 percentage point lower risk of HIV infection about a decade later, from about 25% to about 17% infected.

The study, which also shows expanding secondary schooling to be a very cost effective HIV prevention measure, used a recent school policy reform as a 'natural experiment' to ...

The day will officially be a bit longer than usual on Tuesday, June 30, 2015, because an extra second, or "leap" second, will be added.

"Earth's rotation is gradually slowing down a bit, so leap seconds are a way to account for that," said Daniel MacMillan of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

Strictly speaking, a day lasts 86,400 seconds. That is the case, according to the time standard that people use in their daily lives -- Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC. UTC is "atomic time" -- the duration of one second is based on extremely predictable electromagnetic ...

City College of New York researchers led by chemist George John have developed an eco-friendly biodegradable green "herding" agent that can be used to clean up light crude oil spills on water.

Derived from the plant-based small molecule phytol abundant in the marine environment, the new substance would potentially replace chemical herders currently in use. According to John, professor of chemistry in City College's Division of Science, "the best known chemical herders are chemically stable, non-biodegradable, and hence remain in the marine ecosystem for years."

"Our ...

SACRAMENTO, Calif. -- Low flu vaccination rates, medication compliance and limited access to primary care providers have contributed to the high pediatric asthma rates in California, say UC Davis pediatricians Ulfat Shaikh and Robert Byrd, who have published an extensive study describing the challenges faced by children with asthma in California.

Analyzing data from the 2011-12 California Health Interview Survey, the study details several issues affecting asthma care and offers a number of public policy strategies that could help remedy these shortcomings. The research ...

Research led by Michigan State University could someday lead to the development of new and improved semiconductors.

In a paper published in the journal Science Advances, the scientists detailed how they developed a method to change the electronic properties of materials in a way that will more easily allow an electrical current to pass through.

The electrical properties of semiconductors depend on the nature of trace impurities, known as dopants, which when added appropriately to the material will allow for the designing of more efficient solid-state electronics.

The ...

Athens, Ga. -- Despite heavy development, the U.S. still has millions of acres of pristine wild lands. Coveted for their beauty, these wilderness areas draw innumerable outdoor enthusiasts eager for a taste of primitive nature.

But University of Georgia researchers say these federally protected nature areas have a problem: Their boundaries have become prime real estate.

As the country's population continues to grow, people have built homes close to national parks, forests and wilderness areas for the same reasons these systems have been left protected from development. ...

Baltimore, June 26 -- The flu virus can be lethal. But what is often just as dangerous is the body's own reaction to the invader. This immune response consists of an inflammatory attack, meant to kill the virus. But if it gets too aggressive, this counterattack can end up harming the body's own tissues, causing damage that can lead to death.

Now, a University of Maryland School of Medicine (UM SOM) researcher has for the first time uncovered new details about how this response plays out. Furthermore, he has identified a "decoy" molecule that can rein in this runaway inflammatory ...