(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- The brain hidden inside the oldest known Old World monkey skull has been visualized for the first time. The creature's tiny but remarkably wrinkled brain supports the idea that brain complexity can evolve before brain size in the primate family tree.

The ancient monkey, known scientifically as Victoriapithecus, first made headlines in 1997 when its fossilized skull was discovered on an island in Kenya's Lake Victoria, where it lived 15 million years ago.

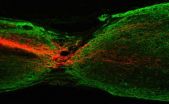

Now, thanks to high-resolution X-ray imaging, researchers have peered inside its cranial cavity and created a three-dimensional computer model of what the animal's brain likely looked like.

Micro-CT scans of the creature's skull show that Victoriapithecus had a tiny brain relative to its body.

Co-authors Fred Spoor of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Lauren Gonzales of Duke University calculated its brain volume to be about 36 cubic centimeters, which is less than half the volume of monkeys of the same body size living today.

If similar-sized monkeys have brains the size of oranges, the brain of this particular male was more akin to a plum.

"When Lauren finished analyzing the scans she called me and said, 'You won't believe what the brain looks like,'" said co-author Brenda Benefit of New Mexico State University, who first discovered the skull with NMSU co-author Monte McCrossin.

Despite its puny proportions, the animal's brain was surprisingly complex.

The CT scans revealed numerous distinctive wrinkles and folds, and the olfactory bulb -- the part of the brain used to perceive and analyze smells -- was three times larger than expected.

"It probably had a better sense of smell than many monkeys and apes living today," Gonzales said. "In living higher primates you find the opposite: the brain is very big, and the olfactory bulb is very small, presumably because as their vision got better their sense of smell got worse."

"But instead of a tradeoff between smell and sight, Victoriapithecus might have retained both capabilities," Gonzales said.

The findings, published in the July 3 issue of Nature Communications, are important because they offer new clues to how primate brains changed over time, and during a period from which there are very few fossils.

"This is the oldest skull researchers have found for Old World monkeys, so it's one of the only clues we have to their early brain evolution," Benefit said.

In the absence of fossil evidence, previous researchers have disagreed over whether primate brains got bigger first, and then more folded and complex, or vice versa.

"In the part of the primate family tree that includes apes and humans, the thinking is that brains got bigger and then they get more folded and complex," Gonzales said. "But this study is some of the hardest proof that in monkeys, the order of events was reversed -- complexity came first and bigger brains came later."

The findings also lend support to claims that the small brain of the human ancestor Homo floresiensis, whose 18,000-year-old skull was discovered on a remote Indonesian island in 2003, isn't as remarkable as it might seem. In spite of their pint-sized brains, Homo floresiensis was able to make fire and use stone tools to kill and butcher large animals.

"Brain size and brain complexity can evolve independently; they don't have to evolve together at the same time," Benefit said.

INFORMATION:

The work was funded by the Max Planck Society and University College London. The skull was originally discovered with support from the National Science foundation (9505778).

CITATION: "Cerebral Complexity Preceded Enlarged Brain Size and Reduced Olfactory Bulbs in Old World Monkeys," L. Gonzales, B. Benefit, M. McCrossin and F. Spoor. Nature Communications, July 2015. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8580.

BARCELONA-LUGANO, 3 July 2015 - The phase IIIb CONSIGN study has confirmed the benefit of regorafenib in patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), researchers announced at the ESMO 17th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer 2015 in Barcelona.(1) The safety profile and progression free survival were similar to phase III trial results.

CONSIGN was a prospective, observational study that was initiated to allow patients with mCRC access to regorafenib before marketing authorisation and to assess safety, which was the primary endpoint. The randomised ...

Spiders travel across water like ships, using their legs as sails and their silk as an anchor, according to research published in the open access journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. The study helps explain how spiders are able to migrate across vast distances and why they are quick to colonise new areas.

Common spiders are frequently observed to fly using a technique called 'ballooning'. This involves using their silk to catch the wind which then lifts them up into the air. Ballooning spiders are estimated to move up to 30 km per day when wind conditions are suitable, helping ...

Scientists have developed a new technique allowing the bioprinting at ambient temperatures of a strong paste similar to 'play dough' capable of incorporating protein-releasing microspheres.

The scientists demonstrated that the bioprinted material, in the form of a micro-particle paste capable of being injected via a syringe, could sustain stresses and strains similar to cancellous bone - the 'spongy' bone tissue typically found at the end of long bones.

This work, published today (3 July 2015) in the journal Biofabrication, suggests that bioprinting at ambient temperatures ...

A therapy that replaces the faulty gene responsible for cystic fibrosis in patients' lungs has produced encouraging results in a major UK trial.

One hundred and thirty six patients aged 12 and over received monthly doses of either the therapy or the placebo for one year.

The clinical trial reached its primary endpoint with patients who received therapy having a significant, if modest benefit in lung function compared with those receiving a placebo.

Patients from across England and Scotland participated, and were treated in two centres, Royal Brompton Hospital in ...

Banded mongooses take extraordinary risks to ensure that they find the right mate.

Female banded mongooses risk their lives to mate with rivals during pack 'warfare' and both males and females have also learned to discriminate between relatives and non-relatives to avoid inbreeding even when mating within their own social group.

Researchers from the University of Exeter and Liverpool John Moores University found that 18% of wild banded mongoose pups are fathered by males from rival packs.

Banded mongooses are found living in stable social groups across Central ...

For the first time gene therapy for cystic fibrosis has shown a significant benefit in lung function compared with placebo, in a phase 2 randomised trial published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine journal. The technique replaces the defective gene response for cystic fibrosis by using inhaled molecules of DNA to deliver a normal working copy of the gene to lung cells.

"Patients who received the gene therapy showed a significant, if modest, benefit in tests of lung function compared with the placebo group and there were no safety concerns," said senior author Professor ...

LAWRENCE -- A new study that is the first to use Social Security Administration's personal income tax data tracking the same individuals over 20 years to measure individual lifetime earnings has confirmed significant long-term economic benefits of college education.

ChangHwan Kim, a University of Kansas researcher, said the research team was also able to account for shortcomings in previous studies by including factors such as gender, race, ethnicity, place of birth and high school performance that would influence a person's lifetime earnings and the probability of college ...

DALLAS, July 2, 2015 -- An emergency room rapid response plan for children can help diagnose stroke symptoms quickly, according to new research in the American Heart Association journal Stroke.

"Just as there are rapid response processes for adults with a possible stroke, there should be a rapid response process for children with a possible stroke that includes expedited evaluation and imaging or rapid transfer to a medical center with pediatric stroke expertise," said Lori Jordan, M.D., Ph.D., study senior author and an assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology ...

Researchers at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) have found a way to stimulate the growth of axons, which may spell the dawn of a new beginning on chronic SCI treatments.

Chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) is a formidable hurdle that prevents a large number of injured axons from crossing the lesion, particularly the corticospinal tract (CST). Patients inflicted with SCI would often suffer a loss of mobility, paralysis, and interferes with activities of daily life dramatically. While physical therapy and rehabilitation would help the patients to ...

Washington, D.C. - July 2, 2015 - Male fruit flies infected with the bacterium, Wolbachia, are less aggressive than those not infected, according to research published in the July Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology. This is the first time bacteria have been shown to influence aggression, said corresponding author Jeremy C. Brownlie, PhD, Deputy Head, School of Natural Sciences, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

The research began with a discovery by University of Arizona student Elizabeth Bondy, an undergraduate ...