"Nitric oxide is used to treat about 35,000 hospitalized U.S. patients each year - mostly adults with pulmonary hypertension and infants with a condition called persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN)," says Warren M. Zapol, MD, director of the MGH Anesthesia Center for Critical Care Research and emeritus chief of Anesthesia and Critical Care at the hospital, senior author of the Science Translational Medicine report. "But NO therapy is very expensive - here at MGH five days treatment of a newborn with PPHN costs around $14,000 - and current systems use gas delivered in heavy tanks, making ambulatory treatment impractical. Our new system can economically make NO from the nitrogen and oxygen in the air using only small amounts of electric power. This device could enable trials of NO to treat patients with chronic lung diseases and certain kinds of heart failure and would make NO therapy available in parts of the world that don't have the resources that are currently required."

Not to be confused with the anesthetic gas nitrous oxide, nitric oxide was long considered to be only a toxic pollutant gas. But in the mid-1980s, three U.S. investigators discovered that it is a signal-transmitting molecule naturally used by the pulmonary, cardiac and other systems, a discovery that received the 1998 Nobel Prize. Among its many function, NO relaxes muscles surrounding blood vessels, which reduces blood pressure - a property that led Zapol and his colleagues to investigate its use to treat hypertension in vessels supplying the lungs. Their discovery that inhaled NO selectively relaxed pulmonary vessels without producing a systemic drop in blood pressure led to the therapy's FDA approval in 1999 for the treatment of PPHN and other lung diseases in newborns. In 2003 Zapol and his former research fellow Claes Frostell, MD, PhD, received the Inventor of the Year award from the Intellectual Property Owners Association for the development of a system to safely deliver inhaled NO.

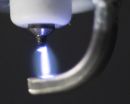

Since its FDA approval NO has been supplied to hospitals in large tanks of compressed gas and administered through bulky and complex delivery devices by trained respiratory therapists. However, in 1992 Zapol and the MGH were issued a patent for a system his team had developed to produce NO - which can be naturally produced by lightning bolts - from air by means of an electrical spark. Although the discovery was licensed by two medical and industrial gas companies, the technology was never developed, possibly because the medical use of inhaled NO was only beginning to be accepted. In addition, the system originally invented by the MGH team was still too large for use in outpatient settings. The growing therapeutic use of NO along with technological advances including the availability of miniaturized electronic circuitry allowed the MGH team to develop the system described in the current report.

The investigators designed and built two prototype systems: in one the NO generator is a separate "offline" system continually generating gas that is delivered into a ventilation system via tubing; the second "inline" system is incorporated into the ventilation system in a way that synchronizes the generation of NO during inhalation with the pulsed delivery of oxygen and other gases to be inhaled, reducing the NO that would be lost during exhalation. Since generation of NO by an electric spark can also produce the toxic gases nitrogen dioxide and ozone, along with metal fragments from the electrode, both systems use calcium hydroxide and air filters to absorb and remove those byproducts.

A series of experiments helped the team determine the best metal to use for the electrode, which was determined to be iridium, and the optimal timing and number of electric sparks. Testing in an animal model revealed that the electrically generated NO produced by both systems was as effective as tank-delivered gas in relieving pulmonary hypertension. Although a gas mixture containing 50 percent oxygen produced the highest NO levels, the amount produced from ambient air was sufficient for therapeutic use. Both systems continued to deliver therapeutic levels of NO for up to 10 days, and subsequent experiments with the inline system not included in this paper have continued for up to 28 days. There's no reason to think the system could not stably produce NO for even longer periods of time, notes Zapol, the Reginald Jenney Professor of Anæsthesia at Harvard Medical School.

"It's amazing how long this system continues to make NO," he says. "Once we've shown that this can safely be used in human patients with pulmonary hypertension - and we've got a clinical trial in progress right now - we'll be able to conduct studies of inhaled NO delivered in ambulatory settings, including patients' homes, to treat chronic pulmonary hypertension, right-sided heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease."

Richard Channick, MD, director of the MGH Pulmonary Hypertension Program, says, "This advance has great potential for our patients. If proven safe and effective, electrically generated NO therapy will greatly enhance our ability to treat many forms of pulmonary hypertension." Marc Semigran, MD, medical director of the MGH Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplant Service adds, "The ability to safely administer inhaled NO chronically to heart failure patients could improve the lives of many of the millions of patients with secondary pulmonary hypertension." Both physicians are collaborators with Zapol's research team although they are not co-authors of the current study.

INFORMATION:

Binglan Yu, PhD, of the MGH Anesthesia Center for Critical Care Research is lead author of the Science Translational Medicine report; additional co-authors are Stefan Muenster, MD, Aron Blaesi, PhD, and Donald Bloch, MD, all of the Anesthesia Center for Critical Care Research. Several additional patent applications covering the new system have been filed, and an option to license those patents has been granted to the startup company Third Pole, Inc.

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $760 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine.