(Press-News.org) LOS ANGELES (July 6, 2015) - Cedars-Sinai researchers have successfully tested two new methods for preserving cognition in laboratory mice that exhibit features of Alzheimer's disease by using white blood cells from bone marrow and a drug for multiple sclerosis to control immune response in the brain.

Under the two approaches, immune cells from outside the brain were found to travel in greater numbers through the blood into the brain. The study showed measurable benefits in mice, an encouraging step toward further testing of these potentially powerful strategies in human trials.

Researchers point out that the brain's own immune cells are critical for its healthy function. During the progression of Alzheimer's disease, these cells are found to be defective. In this study, the researchers discovered that immune cells infiltrating the brain from the blood effectively resisted various abnormalities associated with the condition.

"These cells appear to work in the brain in several ways to counter the negative effects associated with Alzheimer's disease," said Maya Koronyo-Hamaoui, PhD, assistant professor of neurosurgery and biomedical sciences at Cedars-Sinai, and the senior author of the article published in Brain, a journal of Oxford University Press.

"The increasing incidence of Alzheimer's disease and the lack of any effective therapy make it imperative to explore new strategies, especially those that can target multiple abnormalities in such a complicated disease," Koronyo-Hamaoui added.

In Alzheimer's disease, a protein fragment known as amyloid-beta builds up at the synapses of neurons - the point where neuron-to-neuron communication occurs. As a result, synapses are lost and cognitive function becomes severely impaired.

Immune cells in the brain that are exposed to increasing concentrations of the toxic protein fragment deteriorate and lose their ability to attack and clear away the buildup. Over time, these cells themselves go awry, contributing to harmful inflammation and becoming toxic to the neurons.

During the course of the disease, cells that support the brain's structure and function also fail at the cellular and molecular levels, steadily impairing memory and learning functions.

In efforts to boost an effective immune response, the Cedars-Sinai scientists have devised ways to "recruit" white blood cells known as monocytes from bone marrow to attack the protein fragments and preserve the synapses.

The researchers evaluated two such methods and their therapeutic potential. In one, they extracted a specific type of monocytes from the bone marrow of healthy young mice and injected the cells into the tail veins of sick mice once a month. A second group of sick mice received weekly under-the-skin injections of glatiramer acetate, an FDA-approved drug used for the treatment of multiple sclerosis; the drug has been shown to foster the migration of white blood cells from the bloodstream to the brain. A third group received both treatments.

All three groups experienced a substantial decrease in Alzheimer's-like pathology and symptoms.

The varied approaches were effective in "recruiting" protective monocytes to "lesion sites" in the brain, removing protein fragments and reducing harmful inflammation through the secretion of chemicals that regulate immunity at the molecular level, said Koronyo-Hamaoui, the head of Cedars-Sinai's neuroimmunology laboratory at the Maxine Dunitz Neurosurgical Institute and a faculty member in the Department of Neurosurgery and Department of Biomedical Sciences.

In this study, glatiramer acetate was further found to profoundly affect monocytes' function, she added.

"This study provides the evidence that a subgroup of unmodified monocytes, extracted from the bone marrow of healthy mouse donors and grafted into the bloodstream, can migrate into the brains of sick mice, directly clear abnormal protein accumulation and preserve cognitive function," said Yosef Koronyo, the article's first author and a research associate in the Department of Neurosurgery.

Koronyo added that the study gives unprecedented details about monocyte numbers migrating into brain lesion sites and the compounds they secrete, and shows that the body's natural monocytes can have direct effects on the integrity of synapses.

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the Coins for Alzheimer's Research Trust (CART) Fund, the BrightFocus Foundation, the Maurice Marciano Family Foundation, the Saban Family Foundation and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through CTSI grant UL1TR000124. The authors report no competing financial interests.

Citation: Brain, "Therapeutic effects of glatiramer acetate and grafted CD115+ monocytes in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease," published online June 6, 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv150.

Effective Sept. 1, 2015, the media contact for Cedars-Sinai's neurosciences will be Sally Stewart. Sally.Stewart@cshs.org.

New research suggests guidelines on children's exposure to radio frequency waves from technology are confusing for parents.

The review into the polices of 34 countries, carried out by Dr Mary Redmayne, from the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at Monash University, found varying degrees of advice about children's exposure to radio frequency electromagnetic fields (RF-EMF).

RF-EMFs are emitted from technology including WiFi, tablets and mobile phones. Associated with an increased risk of some brain tumours in heavy and long-term phone users, RF-EMFs ...

ARLINGTON HEIGHTS, Ill. (July 7, 2015) - Parents of kids with severe allergies know how scary a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) is. New research offers clues as to why some kids can have a second, related reaction hours later - and what to do about it.

A study in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the scientific publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), examined records of 484 children seen in an emergency department (ED) for anaphylaxis. The researchers tracked whether there was a second, follow-up reaction. Delayed ...

When Greek mythology and cell biology meet, you get the protein Callipygian, recently discovered and named by researchers at The Johns Hopkins University for its role in determining which area of a cell becomes the back as it begins to move.

The findings, made in the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, shed light on how symmetrical, round cells become "polarized," or asymmetrical and directional. A summary of the findings was published online June 30 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Cells have to have a front and a back to migrate," says Peter ...

Scientists have discovered new ways in which the malaria parasite survives in the blood stream of its victims, a discovery that could pave the way to new treatments for the disease.

The researchers at the Medical Research Council's (MRC) Toxicology Unit based at the University of Leicester and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine identified a key protein, called a protein kinase, that if targeted stops the disease. The study is published today (Tuesday) in Nature Communications.

Malaria is caused by a parasite that lives inside an infected mosquito and ...

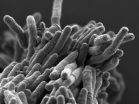

Testing thousands of approved drugs, EPFL scientists have identified an unlikely anti-tuberculosis drug: the over-the-counter antacid lansoprazole (Prevacid®).

Tuberculosis continues to be a global pandemic, second only to AIDS as the greatest single-agent killer in the world. In 2013 alone, the TB bug Mycobacterium tuberculosis caused 1.5 million deaths and almost nine million new infections. Resistance to TB drugs is widespread, creating an urgent need for new medicines. EPFL scientists have now identified lansoprazole, a widely used, over-the-counter antacid, as ...

New research from the University of Copenhagen and Herlev and Gentofte Hospital shows that high vitamin C concentrations in the blood from the intake of fruit and vegetables are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and early death.

Fruit and vegetables are healthy. We all know that. And now there is yet another good reason for eating lots of it. New research from the University of Copenhagen shows that the risk of cardiovascular disease and early death falls with a high intake of fruit and vegetables, and that this may be dued to vitamin C.

The ...

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA (JULY 7, 2015). Researchers at Brown University examined three magnetically programmable shunt valves to see if the magnetic field emissions of headphones can cause unintentional changes in shunt valve settings. Based on their findings, the researchers state that it is highly unlikely that commercially available headphones will interfere with programmable shunt valve settings. Full details of this study can be found in "Programmable shunts and headphones: Are they safe together?" by Heather S. Spader, MD, and colleagues, published today online, ahead ...

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA (JULY 7, 2015). Researchers conducted a prospective observational study in elderly patients and adult patients receiving antiplatelet therapy who presented with mild head injury at two trauma hospitals in Vienna: the Trauma Hospital Meidling and the Donauspital. The focus of the study was to see if blood serum levels of S100B protein in these patients could help identify whether their injuries included intracranial bleeding. If there was no indication of intracranial hemorrhage, these patients would not need additional testing or hospitalization. The ...

Policymakers and developers planning high-density housing near public transit with the goal of reducing automobile use and greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to global warming need a clearer understanding of the health risks from air pollution that may be created if that housing is also built near busy roads and freeways, according to new research by Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California (USC) scientists.

The study is one of the first to focus on the burden of heart disease that can result from residential exposures near major roadways ...

Weather is frequently portrayed in popular music, with a new scientific study finding over 750 popular music songs referring to weather, the most common being sun and rain, and blizzards being the least common. The study also found many song writers were inspired by weather events.

The study, led by the University of Southampton, together with the Universities of Oxford, Manchester, Newcastle (all part of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research) and the University of Reading analysed the weather through lyrics, musical genre, keys and links to specific weather ...