(Press-News.org) Rejection of transplanted organs in hosts that were previously tolerant may not be permanent, report scientists from the University of Chicago. Using a mouse model of cardiac transplantation, they found that immune tolerance can spontaneously recover after an infection-triggered rejection event, and that hosts can accept subsequent transplants as soon as a week after. This process depends on regulatory T-cells, a component of the immune system that acts as a "brake" for other immune cells. The findings, published online in Nature Communications on July 7, support inducing immune tolerance as a viable strategy to achieve life-long transplant survival.

"Transplantation tolerance appears to be a resilient and persistent state, even though it can be transiently overcome," said Anita Chong, PhD, professor of transplantation surgery at the University of Chicago and co-senior author of the study. "Our results change the paradigm that immune memory of a transplant rejection is invariably permanent."

To prevent transplant rejection in patients with end-stage organ failure, a lifelong regimen of immune-suppressing drugs is almost always required. While difficult to achieve, immune tolerance - in which a transplanted organ is accepted without long-term immunosuppression - can be induced in some patients. However, rejection can still be triggered by events such as bacterial infection, even after long periods of tolerance. It has been assumed that the immune system remembers rejection and prevents future transplants from being tolerated.

Chong and her colleagues have previously shown in mice that certain bacterial infections can disrupt tolerance and trigger rejection of an otherwise stable transplant. As they further studied this phenomenon, they made a surprising observation. Infection-triggered rejection caused the number of immune cells that target a transplant to spike in tolerant mice as expected. But they were dramatically reduced seven days post-rejection. This ran counter to rejection in non-tolerant recipients, where these cells remain at elevated levels.

To identify the explanation for this observation, the team grafted a heart into the abdominal cavity of experimental mice and induced immune tolerance. After two months of stable tolerance, the researchers triggered rejection via infection with Listeria bacteria, which caused the transplant to fail. They then grafted a second heart from a genetically identical donor as the first, a week after rejection of the initial graft. This second transplant was readily accepted and remained fully functional over the study period. A second set of experiments, in which a second heart was grafted roughly a month after rejection to give potential immune memory more time to develop, showed similar long-term acceptance.

The team discovered that regulatory T cells (Tregs) - a type of white blood cell that regulates the immune response by suppressing the activity of other immune cells - were required for the restoration of tolerance. When they depleted Tregs in a group of mice one day before the transplantation of the second heart, the newly transplanted organ was rejected. This suggested that Tregs act as a "brake" that prevents other immune cells from targeting and rejecting the second transplant.

"The methods for achieving transplantation tolerance differ between mice and humans, but the mechanisms that maintain it are likely shared," said Marisa Alegre, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and co-senior author on the study. "Our results imply that tolerant patients who experience rejection could be treated with short-term immunosuppressive medications to protect the transplant, and then weaned off once tolerance returns."

In addition to presenting new treatment options for current and future tolerant patients who experience transplant rejection, shedding light on the mechanisms involved in tolerance recovery could lead to the discovery of biomarkers or bioassays that predict whether recipients can be safely taken off immunosuppression.

The findings also hint at possible connections with autoimmune disease and cancer, which both disrupt the immune system's ability to distinguish "self" from "nonself." Better understanding of how immune tolerance is lost and regained could inform efforts toward establishing stronger and more durable phases of remission in autoimmune disease and toward preventing cancer recurrence.

"We're now working to understand in greater detail the mechanisms for how this return of tolerance happens," said study author Michelle Miller, graduate student in molecular medicine at the University of Chicago. "We want to find if there are other mechanisms besides Tregs that mediate tolerance and help prevent memory of the rejection."

INFORMATION:

The study, "Spontaneous restoration of transplantation tolerance after acute rejection," was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Additional authors include Melvin D. Daniels, Tongmin Wang, Jianjun Chen, James Young, Jing Xu, Ying Wang, Dengping Yin, Vinh Vu and Aliya N. Husain.

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- A stroke happens in an instant. And many who survive one report that their brain never works like it once did. But new research shows that these problems with memory and thinking ability keep getting worse for years afterward - and happen faster than normal brain aging.

Stroke survivors also had a faster rate of developing cognitive impairment over the years after stroke compared to their pre-stroke rate. The study results are published in the Journal of the American Medical Association this week.

"We found that stroke is associated with cognitive ...

The Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games brought more than just athletes to B.C. It also left the province with a bad case of the measles.

In research outlined today in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, scientists at the University of British Columbia and the B.C. Centre for Disease Control used genetic sequencing to trace the 2010 measles outbreak, linking it back to an influx of visitors during the Winter Olympics.

"In 2010, we had two visitors, probably from separate parts of the world, who each brought one genotype of measles with them," said lead author Jennifer Gardy, ...

HOUSTON - (July 7, 2015) - Companies that want to increase customers' loyalty and get their repeat business would do well to understand the nuanced ways in which and reasons why a customer is committed to that company, according to a recent study by marketing experts at Rice University and Fordham University. The research provides a strategic blueprint for developing customer commitment.

The researchers tested a customer-commitment model that has five dimensions -- affective, normative, economic, forced and habitual. They said previous research has used an "insufficient" ...

LAWRENCE -- A wide-ranging study of gains and losses of populations of bird species across Mexico in the 20th century shows shifts in temperature due to global climate change are the primary environmental influence on the distributions of bird species.

"Of all drivers examined ... only temperature change had significant impacts on avifaunal turnover; neither precipitation change nor human impacts on landscapes had significant effects," wrote the authors of the study, which appeared recently in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances.

Using analytical techniques from ...

URBANA, Ill. - A recent study looked at marijuana and alcohol use in people between the ages of 18 and 24. It's probably not surprising that the results show a drastic increase in alcohol consumption in people just over 21; after all, that's the minimum legal age to drink. What University of Illinois economist Ben Crost found remarkable is that, at the same age, there was an equally dramatic drop in marijuana use.

"Alcohol appears to be a substitute for marijuana. This sudden decrease in the use of marijuana is because they suddenly have easy access to alcohol," Crost ...

ATLANTA--Structural brain abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia, providing insight into how the condition may develop and respond to treatment, have been identified in an internationally collaborative study led by a Georgia State University scientist.

Scientists at more than a dozen locations across the United States and Europe analyzed brain MRI scans from 2,028 schizophrenia patients and 2,540 healthy controls, assessed with standardized methods at 15 centers worldwide. The findings, published in Molecular Psychiatry, help further the understanding of the mental ...

Researchers from the University of Houston found that some natural gas wells, compressor stations and processing plants in the Barnett Shale leak far more methane (CH4) than previously estimated, potentially offsetting the climate benefits of natural gas.

The study is one of 11 papers published in the July 7 edition of Environmental Science & Technology, all looking at fugitive methane emissions in the Barnett Shale. That region, site of the first widespread shale development in the United States, includes Dallas-Fort Worth and almost two dozen counties to the west ...

Effectiveness shown in tests on ovarian and bowel cancer

Drug can shut down a cancer cell's metabolism

Developed by researchers at the University of Warwick's Warwick Cancer Research Centre

Tests conducted by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute's Cancer Genome Project

New drug could be cheaper to produce and less harmful to healthy cells

Tests have shown that a new cancer drug, FY26, is 49 times more potent than the clinically used treatment Cisplatin.

Based on a compound of the rare precious metal osmium and developed by researchers at the University of Warwick's ...

Professor Richard Lilford and Dr Yen-Fu Chen of the University's Warwick Medical School, raised the issue following a study that states hospital weekend death risk is common in several developed countries - not just England

Professor Lilford, said: "Understanding this is an extremely important task since it is large, at about 10% in relative risk terms and 0.4% in percentage point terms. This amounts to about 160 additional deaths in a hospital with 40,000 discharges per year.

"But how much of the observed increase results from service failure? And here is the rub, ...

This news release is available in German.

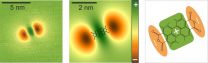

Jülich, 7 July - Using a single molecule as a sensor, scientists in Jülich have successfully imaged electric potential fields with unrivalled precision. The ultrahigh-resolution images provide information on the distribution of charges in the electron shells of single molecules and even atoms. The 3D technique is also contact-free. The first results achieved using "scanning quantum dot microscopy" have been published in the current issue of Physical Review Letters. The related publication was chosen as ...