(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. - Children with even mild or passing bouts of depression, anxiety and/or behavioral issues were more inclined to have serious problems that complicated their ability to lead successful lives as adults, according to research from Duke Medicine.

Reporting in the July 15 issue of JAMA Psychiatry, the Duke researchers found that children who had either a diagnosed psychiatric condition or a milder form that didn't meet the full diagnostic criteria were six times more likely than those who had no psychiatric issues to have difficulties in adulthood, including criminal charges, addictions, early pregnancies, education failures, residential instability and problems getting or keeping a job.

"When it comes to key psychiatric problems -- depression, anxiety, behavior disorders -- there are successful interventions and prevention programs," said lead author William Copeland, Ph.D., assistant clinical professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke. "So we do have the tools to address these, but they aren't implemented widely. The burden is then later seen in adulthood, when these problems become costly public health and social issues."

Copeland and colleagues analyzed data from the Great Smoky Mountains Study, which began nearly two decades ago and includes 1,420 participants from 11 North Carolina counties. The study is ongoing and has followed the participants from childhood through adulthood -- most are now in their 30s.

Among the study group, 26.2 percent met the criteria for depression, anxiety or a behavioral disorder in childhood; 31 percent had milder forms that were below the full threshold of a diagnosis; and 42.7 percent had no identified problems.

The researchers found that as these children grew into adults, even some of those who had no psychiatric diagnosis as children -- nearly one in five -- stumbled in adulthood, suggesting that difficulties were not limited to those with psychiatric diagnoses.

But having a psychiatric diagnosis or a close call dramatically raised the odds that adulthood would have rough patches. This was the case even if they did not continue to have psychiatric problems in adulthood.

Of those with the milder psychiatric indicators as kids, 41.9 percent had at least one of the problems in adulthood that complicates success, and 23.2 percent had more than one such issue. For those who met the full psychiatric diagnosis criteria, 59.5 percent had a serious challenge as adults, and 34.2 percent had multiple problems.

Copeland said specific psychiatric disorders were associated with specific adult problems, but the best predictor of having adult issues was having multiple psychiatric problems as kids.

"When we went into this, it was an open question: Are these psychiatric diagnoses in childhood impairing in the moment, but something people recover from and go on?" Copeland said. "We weren't expecting to find these protracted difficulties into adulthood."

Copeland said the findings reinforce the need to attack problems early with effective therapies. He said only about 40 percent of children get the treatment they need for psychiatric disorders, and even fewer who have borderline problems are treated.

"A big problem with mental health in the United States is that most children don't get treatment and those who do don't get what we would consider optimal care," Copeland said. "So the problems go on much longer than they need to and cost much more than they should in both money and damaged lives."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Copeland, study authors include Dieter Wolke, Lilly Shanahan and E. Jane Costello.

The study received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH080230, MH63970, MH63671, MH48085, MH075766, MH094605); the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/MH11301, DA011301, DA016977, DA036523); the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; and the William T. Grant Foundation.

Children with psychiatric problems were more likely to have health, legal, financial and social problems as adults even if their psychiatric disorders did not persist into adulthood and even if they did not meet the full diagnostic criteria for a disorder, according to an article published online by JAMA Psychiatry.

Neuropsychiatric disorders among young people ages 10 to 24 are a leading cause of disease burden globally. Unlike many chronic physical health problems, most psychiatric disorders are first diagnosed in childhood, which allows the disorder to affect a person's ...

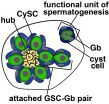

PHILADELPHIA - Stem cells are key for the continual renewal of tissues in our bodies. As such, manipulating stem cells also holds much promise for biomedicine if their regenerative capacity can be harnessed. However, understanding how stem cells govern normal tissue renewal is a field still in its infancy.

Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania are making headway in this area by studying stem cells in their natural environment in an organism. Stem cell populations reside in areas called niches deep within different types of organs. ...

States with more restrictive alcohol policies and regulations have lower rates of self-reported drunk driving, according to a new study by researchers at the Boston University schools of public health and medicine and the University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

The research team assigned each state an "alcohol policy score," based on an aggregate of 29 alcohol policies, such as alcohol taxation and the use of sobriety checkpoints. Each 1 percentage point increase in the score was found to be associated with a 1 percent decrease in the likelihood of impaired driving, ...

Final results of the randomized intergroup EORTC, LYSA (Lymphoma Study Association), FIL (Fondazione Italiana Linfomi) H10 trial presented at the 13th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland, on 19 June 2015 show that early FDG-PET ( 2-deoxy-2[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography) adapted treatment improves the outcome of early FDG-PET-positive patients with stages I/II Hodgkin lymphoma.

Dr. John Raemaekers of the Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen and the Rijnstate Hospital Arnhem, The Netherlands, and EORTC principal ...

HOUSTON - (July 15, 2015) - Three-dimensional structures of boron nitride might be the right stuff to keep small electronics cool, according to scientists at Rice University.

Rice researchers Rouzbeh Shahsavari and Navid Sakhavand have completed the first theoretical analysis of how 3-D boron nitride might be used as a tunable material to control heat flow in such devices.

Their work appears this month in the American Chemical Society journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

In its two-dimensional form, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), aka white graphene, looks ...

A University of Toronto research team has discovered new details about a key gene involved in ALS, perhaps humanity's most puzzling, intractable disease.

In this fatal disorder with no effective treatment options, scientists (including members of U of T) achieved a major breakthrough in 2011 when they discovered mutations in the gene C9orf72, as the most frequent genetic cause of ALS and frontotemporal dementia. But little was known about how this gene and its related protein worked in the cell.

To solve this problem, Professor Janice Robertson and her team at the ...

Sapphirina, or sea sapphire, has been called "the most beautiful animal you've never seen," and it could be one of the most magical. Some of the tiny, little-known copepods appear to flash in and out of brilliantly colored blue, violet or red existence. Now scientists are figuring out the trick to their hues and their invisibility. The findings appear in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and could inspire the next generation of optical technologies.

Copepods are tiny aquatic crustaceans that live in both fresh and salt water. Some males of the ocean-dwelling ...

Five years ago this week, engineers stopped the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill -- the largest one in U.S. history, easily displacing the Exxon Valdez spill from the top spot. Now, Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society, takes a look at the lessons scientists are learning from these accidents to improve clean-up efforts and, perhaps, prevent spills altogether.

C&EN Senior Editor Jyllian Kemsley explains that although both spills were caused by human error, they each posed unique challenges. When the tanker Exxon ...

"No swimming" signs have already popped up this summer along coastlines where fecal bacteria have invaded otherwise inviting waters. Some vacationers ignore the signs while others resign themselves to tanning and playing on the beach. But should those avoiding the water be wary of the sand, too? New research in the ACS journal Environmental Science & Technology investigates reasons why the answer could be "yes."

Sewage-contaminated coastal waters can lead to stomach aches, diarrhea and rashes for those who accidentally swallow harmful microbes or come into contact with ...

A mixture of bitumen and gasoline-like solvents known as dilbit that flows through Prairie pipelines can seriously harm fish populations, according to research out of Queen's University and the Royal Military College of Canada.

At toxic concentrations, effects of dilbit on exposed fish included deformities and clear signs of genetic and physiological stress at hatch, plus abnormal or uninflated swim bladders, an internal gas-filled organ that allows fish to control their buoyancy. Exposure to dilbit reduces their rate of survival by impairing their ability to feed and ...