INFORMATION:

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit http://www.whoi.edu

Carbon dioxide pools discovered in Aegean Sea

2015-07-16

(Press-News.org) The location of the second largest volcanic eruption in human history, the waters off Greece's Santorini are the site of newly discovered opalescent pools forming at 250 meters depth. The interconnected series of meandering, iridescent white pools contain high concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) and may hold answers to questions related to deepsea carbon storage as well as provide a means of monitoring the volcano for future eruptions.

"The volcanic eruption at Santorini in 1600 B.C. wiped out the Minoan civilization living along the Aegean Sea," said Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) scientist Rich Camilli, lead author of a new study published today in the journal Scientific Reports. "Now these never-before-seen pools in the volcano's crater may help our civilization answer important questions about how carbon dioxide behaves in the ocean."

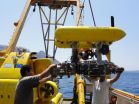

Camilli and his colleagues from the University of Girona, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, and Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR), working in the region in July 2012, used a series of sophisticated underwater exploration vehicles to locate and characterize the pools, which they call the Kallisti Limnes, from ancient Greek for "most beautiful lakes." A prior volcanic crisis in 2011 had led the researchers to initiate their investigation at a site of known hydrothermal activity within the Santorini caldera. During a preliminary reconnaissance of a large seafloor fault the University of Girona's autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Girona 500 identified subsea layers of water with unusual chemical properties.

Following the AUV survey, the researchers then deployed HCMR's Thetis human occupied vehicle. The submersible's crew used robotic onboard chemical sensors to track the faint water column chemical signature up along the caldera wall where they discovered the pools within localized depressions of the caldera wall. Finally, the researchers sent a smaller remotely operated vehicle (ROV), to sample the pools' hydrothermal fluids.

"We've seen pools within the ocean before, but they've always been brine pools where dissolved salt released from geologic formations below the seafloor creates the extra density and separates the brine pool from the surrounding seawater," said Camilli. "In this case, the pools' increased density isn't driven by salt - we believe it may be the CO2 itself that makes the water denser and causes it to pool."

Where is this CO2 coming from? The volcanic complex of Santorini is the most active part of the Hellenic Volcanic Arc. The region is characterized by earthquakes caused by the subduction of the African tectonic plate underneath the Eurasian plate. During subduction, CO2 can be released by magma degassing, or from sedimentary materials such as limestone which undergo alteration while being subjected to enormous pressure and temperature.

The researchers determined that the pools have a very low pH, making them quite acidic, and therefore, devoid of calcifying organisms. But, they believe, silica-based organisms could be the source of the opal in the pool fluids.

Until the discovery of these CO2-dense pools, the assumption has been that when CO2 is released into the ocean, it disperses into the surrounding water. "But what we have here," says Camilli, "is like a 'black and tan' - think Guinness and Bass - where the two fluids actually remain separate" with the denser CO2 water sinking to form the pool.

The discovery has implications for the build up of CO2 in other areas with limited circulation, including the nearby Kolumbo underwater volcano, which is completely enclosed. "Our finding suggests the CO2 may collect in the deepest regions of the crater. It would be interesting to see," Camilli said, adding it does have implications for carbon capture and storage.

Sub-seafloor storage is gaining acceptance as a means of reducing heat-trapping CO2 in the atmosphere and lessening the acidifying impacts of CO2 in the ocean. But before fully embracing the concept, society needs to understand the risks involved in the event of release.

Temperature sensors installed by the team revealed that the Kallisti Limnes were 5°C above that of surrounding waters. According to co-author Javier Escartin, "this heat is likely the result of hydrothermal fluid circulation within the crust and above a deeper heat source, such as a magma chamber." These temperatures may provide a useful gauge to study the evolution of the system. Escartin added that "temperature records of hydrothermal fluids can show variations in heat sources at depth such as melt influx to the magma chamber. The pool fluids also respond to variations in pressure, such as tides, and this informs us of the permeability structure of the sub-seafloor." Changes in the pools' temperature and chemical signals may thus complement other monitoring techniques as useful indicators of increased or decreased volcanism.

This European - American research collaboration was funded through support from the EU Eurofleets program, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, the US National Science Foundation, and NASA's astrobiology program (ASTEP) which supports autonomous technology development to search for life on other planets. "From a technology perspective, it was a big step forward," Camilli said.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genetic markers linking risk for type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's identified

2015-07-16

Certain patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) may have specific genetic risk factors that put them at higher risk for developing Alzheimer's disease (AD), according to a study conducted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published recently in Molecular Aspects of Medicine.

Under the leadership of Giulio Maria Pasinetti, MD, PhD, Saunders Family Chair and Professor of Neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Director of Biomedical Training in the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers at J.J. Peters Bronx VA Medical Center, ...

Personalized care for aortic aneurysms, based on gene testing, has arrived

2015-07-16

New Haven, Conn. -- Researchers at the Aortic Institute at Yale have tested the genomes of more than 100 patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms, a potentially lethal condition, and provided genetically personalized care. Their work will also lead to the development of a "dictionary" of genes specific to the disease, according to researchers.

The study published early online in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.

Experts have known for more than a decade that thoracic aortic aneurysms -- abnormal enlargements of the aorta in the chest area --run in families and are caused ...

New family of chemical structures can effectively remove CO2 from gas mixtures

2015-07-16

A newly discovered family of chemical structures, published in Nature today, could increase the value of biogas and natural gas that contains carbon dioxide.

The new chemical structures, known as zeolites, have been created by an international team of researchers including Professor Xiaodong Zou and co-workers from the Department of Materials and Environmental Chemistry at Stockholm University.

The zeolites -- crystalline aluminosilicates with frameworks that contain windows and cavities the size of small molecules -- can separate out carbon dioxide more effectively ...

Long-sought phenomenon finally detected

2015-07-16

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Part of a 1929 prediction by physicist Hermann Weyl -- of a kind of massless particle that features a singular point in its energy spectrum called the "Weyl point," -- has finally been confirmed by direct observation for the first time, says an international team of physicists led by researchers at MIT. The finding could lead to new kinds of high-power single-mode lasers and other optical devices, the team says.

For decades, physicists thought that the subatomic particles called neutrinos were, in fact, the massless particles that Weyl had predicted -- ...

UAlberta scientists part of unprecedented worldwide biodiversity study

2015-07-16

EDMONTON (July 16, 2015)--Humans depend on high levels of ecosystem biodiversity, but due to climate change and changes in land use, biodiversity loss is now greater than at any time in human history. Five University of Alberta researchers, including students, participated in a leading global initiative to determine whether there are widespread and consistent patterns in plant biodiversity.

Sixty-two scientists from 19 countries spanning six continents studied the relationships between plant biomass production and species diversity, culminating in a paper appearing in ...

Neuroscience-based algorithms make for better networks

2015-07-16

PITTSBURGH--When it comes to developing efficient, robust networks, the brain may often know best.

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have, for the first time, determined the rate at which the developing brain eliminates unneeded connections between neurons during early childhood.

Though engineers use a dramatically different approach to build distributed networks of computers and sensors, the research team of computer scientists discovered that their newfound insights could be used to improve the robustness and ...

How can you plan for events that are unlikely, hard to predict and highly disruptive

2015-07-16

The Ebola epidemic and resulting international public health emergency is referred to as a "Black Swan" event in medical circles because of its unpredictable and impactful nature. However, a paper in the

June 30 issue of Clinical Infectious Diseases, a leading journal in the field of infectious diseases, suggests that the response of the Chicago Ebola Response Network (CERN) in 2014-2015 has laid a foundation and a roadmap for how a regional public health network can anticipate, manage and prevent the next Black Swan public health event.

By sharing the expertise, risk ...

Burden of dengue, chikungunya in India far worse than understood

2015-07-16

New Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health research finds new evidence that an extremely high number of people in southern India are exposed to two mosquito-borne viruses -- dengue and chikungunya.

These findings, the researchers say, reinforce the need for officials to be on the lookout for these diseases and to find ways to control its spread not only in India but also around the world.

The researchers, reporting July 16 in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, tested blood samples from 1,010 people across 50 locations in Chennai, a city with over 6 million people ...

New in the Hastings Center Report: Disclosing misattributed parentage, treating terrorists, informed consent in the era of personalized medicine, and more in the July-August 2015 issue

2015-07-16

When Should Genome Researchers Disclose Misattributed Parentage?

Amulya Mandava, Joseph Millum, and Benjamin E. Berkman

As genome sequencing improves, researchers will increasingly use it on parents and their children when the children have rare or undiagnosed diseases that might be genetic. However, researchers are sure to discover that, in a growing number of cases, the assumed biological relationships between the individuals do not exist. Consequently, the researchers will have to decide whether to disclose incidental findings of misattributed parentage on a much ...

Women and fragrances: Scents and sensitivity

2015-07-16

Researchers have sniffed out an unspoken rule among women when it comes to fragrances: Women don't buy perfume for other women, and they certainly don't share them.

Like boyfriends, current fragrance choices are hands off, forbidden--neither touch, nor smell. You can look, but that's all, says BYU industrial design professor and study coauthor Bryan Howell.

"Women treasure fragrances as a vital pillar of their personal identity," said Howell, who caught wind of the finding while researching fragrance-packaging preferences. "They may use the same fragrance for many years, ...