Research reported July 15 in the journal Angewandte Chemie International Edition demonstrates that important molecules of contemporary life, known as polypeptides, can be formed simply by mixing amino and hydroxy acids - which are believed to have existed together on the early Earth - then subjecting them to cycles of wet and dry conditions. This simple process, which could have taken place in a puddle drying out in the sun and then reforming with the next rain, works because chemical bonds formed by one compound make bonds easier to form with the other.

The research supports the theory that life could have begun on dry land, perhaps even in the desert, where cycles of nighttime cooling and dew formation are followed by daytime heating and evaporation. Just 20 of these day-night, wet-dry cycles were needed to form a complex mixture of polypeptides in the lab. The process also allowed the breakdown and reassembly of the organic materials to form random sequences that could have led to the formation of the polypeptide chains that were needed for life.

"The simplicity of using hydration-dehydration cycles to drive the kind of chemistry you need for life is really appealing," said Nicholas Hud, a professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and director of the NSF Center for Chemical Evolution, which is also supported by the NASA Astrobiology Program. "It looks like dry land would have provided a very favorable environment for getting the chemistry necessary for life started."

Origin-of-life scientists had previously made polypeptides from amino acids by heating them well past the boiling point of water, or by driving polymerization with activating chemicals. But the high temperatures are beyond the point at which most life could survive, and the robust availability of activating chemicals on the early Earth is questionable. The simplicity of the wet-dry cycle therefore makes it attractive to explain how peptides could have formed, Hud added.

The idea for combining chemically similar amino acids and hydroxyl acids was inspired by the demonstration that polyesters are easy to form by repetitive hydration-dehydration cycles and the fact that esters are activated to attack by the amino group of amino acids. The potential importance of this reaction in the earliest stages of life is supported by studies of meteorites, which revealed that both compounds would have been present on the prebiotic Earth.

Hydroxy acids combine to form polyester, better known as a synthetic textile fiber, and that reaction requires less energy than formation of the amide bonds needed to create peptides from amino acids. In the wet-dry cycles, formation of polyester comes first - which then facilitates the more difficult peptide formation, Hud said.

"The ester linkages that we are making in the polyester can serve as an activating agent formed within the solution," he explained. "Over the course of a very simple chemical evolution, the polymers progress from having hydroxy acids with ester linkages to amino acids with peptide linkages. The hydroxy acids are gradually replaced through the wet and dry cycles because the ester bonds holding them together are not as stable as the peptide bonds."

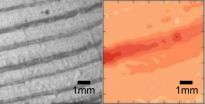

Experimentally, graduate student Sheng-Sheng Yu put the amino and hydroxy acid mixtures through 20 wet-dry cycles to produce molecules that are a mixture of polyesters and peptides, containing as many as 14 units. After just three cycles, and at temperatures as low as 65 degrees Celsius, peptides consisting of two and three units began to form. Postdoctoral fellow Jay Forsythe confirmed the chemical structures using NMR mass spectrometry.

"We allowed the peptide bonds to form because the ester bonds lowered the energy barrier that needed to be crossed," Hud added.

On the early Earth, those cycles could have taken 20 days and nights - or perhaps much longer if the heating and drying cycles corresponded to seasons of the year.

Beyond easily forming the polypeptides, the wet-dry process has an additional advantage. It allows compounds like peptides to be regularly broken apart and reformed, creating new structures with randomly-ordered amino acids. This ability to recycle the amino acids not only conserves organic material that may have been in short supply on the early Earth, but also provides the potential for creating more useful combinations.

A combination of hydroxy and amino acids likely existed in the prebiotic soup of the early Earth, but analyzing such a "messy" reaction was challenging, Hud said. "We were led into this idea that a mixture might work better than separate components," he explained. "It might have been messy at the start, but it's easier to get going than a pristine chemical reaction."

Beyond helping explain how life might have started, the wet-dry cycles could also provide a new way to synthesize polypeptides. Existing techniques produce the chemicals through genetic engineering of microorganisms, or through synthetic organic chemistry. The wet-dry cycling could provide a simpler and more sustainable water-based process for producing these chemicals.

The demonstration of peptide formation opens the door to asking other questions about how life may have gotten going in prebiotic times, said Ramanarayanan Krishnamurthy, a member of the research team and an associate professor of chemistry at the Scripps Research Institute. Future studies will include a look at the sequences formed, whether there are sequences favored by the process, and what sequences might result. The process could ultimately lead to reactions able to continue without the wet-dry cycles.

"If this process were repeated many times, you could grow up a peptide that could acquire a catalytic property because it had reached a certain size and could fold in a certain way," Krishnamurthy said. "The system could begin to develop certain emergent characteristics and properties that might allow it to self-propagate."

INFORMATION:

In addition to those already named, the paper's authors include Irena Mamajanov, Martha A Grover, and Facundo M. Fernández, all from Georgia Tech.

This research was supported by the NSF and the NASA Astrobiology Program under the NSF Center for Chemical Evolution through grant number CHE-1004570. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF or NASA.

CITATION: Jay G. Forsythe, et al., "Ester-Mediated Amide Bond Formation Driven by Wet-Dry Cycles: A Possible Path to Polypeptides on the Prebiotic Earth," (Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2015).