Teeth reveal lifetime exposures to metals, toxins

2015-07-22

(Press-News.org) (NEW YORK CITY - July 22, 2015) Is it possible that too much iron in infant formula may potentially increase risk for neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's in adulthood -- and are teeth the window into the past that can help us tell? This and related theories were described in a "Perspectives" article authored by researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the University of Technology Sydney and Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Australia, and published online recently in Nature Reviews Neurology.

"Teeth are of particular interest to us for the measurement of chemical exposure in fetal and childhood development: they provide a chronological record of exposure from their microchemical composition in relation to defined growth lines, much like the rings in a tree trunk," said Manish Arora, BDS, MPH, PhD, Director of Exposure Biology at the Senator Frank Lautenberg Environmental Health Sciences Laboratory at Mount Sinai and Associate Professor in Preventive Medicine and Dentistry at the Icahn School of Medicine. "Our analysis of iron deposits in teeth as a method for retrospective determination of exposure is just one application: we believe teeth have the potential to help track the impact of pollution on health globally."

Dr. Arora, along with Dominic Hare, PhD, used the dental biomarker technology to distinguish breast-fed babies from formula fed babies. Now this technology can be applied to study the link between early iron exposure and late-life brain diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, which are associated with the abnormal processing of iron. While not all formula fed babies will experience neurodegeneration in adulthood, the combination of increased iron intake during infancy with a predisposition to impaired metal metabolism such as the inability of brain cells to remove excessive metals may damage those cells over time.

Dr. Hare, a Chancellor's Research Fellow in the Elemental Bio-imaging Facility at the University of Technology Sydney, says "Only now do we have the technology available to use to look back in time at someone's diet as a child, more than 60 years after they stopped wearing diapers. State-of-the-art imaging technology is a chemical time machine that can tell us about decades-old chemical exposures that are equivalent to a drop of ink in a swimming pool."

In the case of baby formula, the need to better understand human iron metabolism has become more urgent with the global popularity of formula and fortified cereals. Adding iron to formula has been an industry standard for decades, in part because about two billion people worldwide - mostly in developing nations - are thought to have chronic anemia and iron deficiency. Evidence, however, that children in the United States or Europe, for instance, get too little iron is insufficient, according to the authors, and the reported developmental and nutritional benefits of iron are modest. The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition have since stated that there's no evidence that babies of normal birthweight need iron supplementation, yet in the U.S. it's still commonplace. Dr. Hare continues: "While it might seem like drawing a long bow linking what happens in childhood to diseases we think of as associated with growing old, the increasing rates of these diseases mean we need to do everything we can to find out what might play a role in how the disease starts. Knowing this gives us something to target when designing new treatments."

Beyond the wide-reaching hypothesis that iron supplementation may increase risk of neurodegeneration, the authors think a priority in pediatric research should be the rigorous determination of iron supplementation needs of infants according to their individual iron status. Formula manufacturers have a responsibility to replicate the chemical composition of breast milk, particularly with regard to iron content. The current 'one size fits all' approach to iron supplementation may be both clinically unnecessary and introduce an unacceptable risk later in life. Whether this hypothesis proves to be true or not, it calls into question decades of treatment dogma that deserves to be revisited with the most cutting-edge technology available.

INFORMATION:

About the Mount Sinai Health System

The Mount Sinai Health System is an integrated health system committed to providing distinguished care, conducting transformative research, and advancing biomedical education. Structured around seven hospital campuses and a single medical school, the Health System has an extensive ambulatory network and a range of inpatient and outpatient services--from community-based facilities to tertiary and quaternary care.

The System includes approximately 6,100 primary and specialty care physicians; 12 minority-owned free-standing ambulatory surgery centers; more than 140 ambulatory practices throughout the five boroughs of New York City, Westchester, Long Island, and Florida; and 31 affiliated community health centers. Physicians are affiliated with the renowned Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which is ranked among the highest in the nation in National Institutes of Health funding per investigator. The Mount Sinai Hospital is nationally ranked as one of the top 25 hospitals in 8 specialties in the 2014-2015 "Best Hospitals" issue of U.S. News & World Report. Mount Sinai's Kravis Children's Hospital also is ranked in seven out of ten pediatric specialties by U.S. News & World Report. The New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai is ranked nationally, while Mount Sinai Beth Israel, Mount Sinai St. Luke's, and Mount Sinai Roosevelt are ranked regionally.

For more information, visit http://www.mountsinai.org or find Mount Sinai on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-07-22

LOS ANGELES (July 22, 2015) - For the first time, researchers have employed a gene-editing technique involving low-dose irradiation to repair patient cells, according to a study published in the journal Stem Cells Translational Medicine. This method, developed by researchers in the Cedars-Sinai Board of Governors Regenerative Medicine Institute, is 10 times more effective than techniques currently in use.

"This novel technique allows for far more efficient gene editing of stem cells and will increase the speed of new discoveries in the field," said co-senior author Clive ...

2015-07-22

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Coral reefs, under pressure from climate change and direct human activity, may have a reduced ability to protect tropical islands against wave attack, erosion and salinization of drinking water resources, which help to sustain life on those islands. A new paper gives guidance to coastal managers to assess how climate change will affect a coral reef's ability to mitigate coastal hazards.

About 30 million people are dependent on the protection by coral reefs as they live on low-lying coral islands and atolls. At present, some of these islands experience ...

2015-07-22

Poor schools that have more black and minority students tend to punish students rather than seek medical or psychological interventions for them, according to a Penn State sociologist.

"There's been a real push toward school safety and there's been a real push for schools to show they are being accountable," said David Ramey, assistant professor of sociology and criminology. "But, any zero-tolerance policy or mandatory top-down solutions might be undermining what would be otherwise good efforts at discipline, and not establishing an environment based around all the options ...

2015-07-22

BEER-SHEVA, Israel...July 22, 2015 - Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) and University of Colorado researchers have developed a dynamic "smart" drug that targets inflammation in a site-specific manner and could enhance the body's natural ability to fight infection and reduce side effects.

The uniqueness of this novel anti-inflammatory molecule, reported in the current issue of Journal of Immunology, can be found in a singular property. When injected, it is as a non-active drug. However, a localized site with excessive inflammation will activate it. Most other anti-inflammatory ...

2015-07-22

Edward Snowden's leak of classified documents to journalists around the world about massive government surveillance programs and threats to personal privacy ultimately resulted in a Pulitzer Prize for public service.

Though Snowden had no intention of hiding his identity, the disclosures also raised new questions about how effectively news organizations can protect anonymous sources and sensitive information in an era of constant data collection and tracking.

A new study by University of Washington and Columbia University researchers that will be presented next month ...

2015-07-22

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, July 22, 2015 - In a large population-based study of randomly selected participants in Germany, researchers found that mild cognitive impairment (MCI) occurred significantly more often in individuals diagnosed with a lower ankle brachial index (ABI), which is a marker of generalized atherosclerosis and thus cumulative exposure to cardiovascular risk factors during lifetime. Interestingly, this strong association was only observed in patients with non-amnestic MCI, but not amnestic MCI. There also was no independent association of MCI and intima ...

2015-07-22

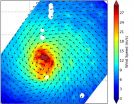

Typhoon Halola's strongest typhoon-force winds were located on the northern half of the storm, as identified from the RapidScat instrument that flies aboard the International Space Station.

RapidScat gathered surface wind data on the Typhoon Halola on July 21at 2 p.m. GMT (10 a.m. EDT). RapidScat data showed that the strongest sustained winds stretched from northwest to northeast of the center at speeds up to 30 meters per second (108 kph/67 mph). Strong winds wrapped around the center of circulation from northwest to east to the southern quadrant, while the weakest winds ...

2015-07-22

Much to his own surprise, Hannes Baur from the Natural History Museum Bern not only reports on whole two new parasitoid wasps at the heart of Europe, the Swiss Alps and Swiss Central Plateau. While the common discovery usually involves cryptic, or "camouflaging" within their groups species, his stand out. Baur's work is published in the open-access journal ZooKeys.

The insects he describes are visibly quite unique with their body structures. In the case of the Pteromalus briani wasp, its extraordinarily protruding hind legs differentiate it among the whole family. Meanwhile, ...

2015-07-22

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- A study of the West Nile virus risk associated with "dry" water-detention basins in Central Illinois took an unexpected turn when land managers started mowing the basins. The mowing of wetland plants in basins that failed to drain properly led to a boom in populations of Culex pipiens mosquitoes, which can carry and transmit the deadly virus, researchers report.

A paper describing their findings is in press in the journal Ecological Applications.

The team, led by University of Illinois postdoctoral researcher Andrew Mackay, found that mowing down cattails ...

2015-07-22

GeoSpace

Warmer air, less sea ice lead to mercury decline in Arctic Ocean

The amount of mercury in the Arctic Ocean is declining as the region rapidly warms and loses sea ice, according to a new study. A new study in Geophysical Research Letters suggests that fish, marine mammals, polar bears, whales and humans in the Arctic might potentially be consuming lower amounts of toxic methylmercury as the region warms.

Eos.org

Puzzles invite you to explore Earth with interactive imagery

The EarthQuiz challenge can take you to virtual field locations with just the click of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Teeth reveal lifetime exposures to metals, toxins