(Press-News.org) Scientists have long worked to understand how crystals grow into complex shapes. Crystals are important in materials from skeletons and shells to soils and semiconductor materials, but much is unknown about how they form.

Now, an international group of researchers has shown how nature uses a variety of pathways to grow crystals that go beyond the classical, one-atom-at-a-time route.

The findings, published today (Thursday, July 30) in Science, have implications for decades-old questions in science and technology regarding how animals and plants grow minerals into shapes that have no relation to their original crystal symmetry, and why some contaminants are so difficult to remove from stream sediments and groundwater.

"Researchers across all disciplines have made observations of skeletons and laboratory grown crystals that cannot be explained by traditional theories," said Patricia Dove, a University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech and the C.P. Miles Professor of Science in the College of Science. "We show how these crystals can be built up into complex structures by attaching particles -- as nanocrystals, clusters, or droplets -- that become organized into complex shapes. Many scientists have contributed to identifying these particles and pathways to becoming a crystal -- our challenge was to put together a framework to understand them."

The results emerged from discussions among 15 scientists working in the fields of geochemistry, physics, biology, and the earth and materials sciences. At home, these researchers conduct lab experiments, investigate animal skeletons, study soils and streams, or use computer simulations to visualize how particles can form and attach.

The international group met for a three-day workshop in Berkeley, California that was sponsored by the Council on Geosciences of the Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy.

"Because crystallization is a ubiquitous phenomenon across a wide range of scientific disciplines, a shift in the picture of how this process occurs has far-reaching consequences," said materials scientist and physicist James De Yoreo at the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. "Moreover, because we largely show a community consensus on this topic, the study has the potential to define the directions of future research on crystallization."

In animal and laboratory systems alike, the process begins by forming the particles. They can be small molecules, clusters, droplets, or nanocrystals. All of these particles are unstable and begin to combine with each other and with nearby crystals and other surfaces.

For example, nanocrystals prefer to become oriented along the same direction as the larger crystal before attaching, much like adding Legos. In contrast, amorphous conglomerates can simply aggregate. These atoms later become organized by "doing the wave" through the mass to rearrange into a single crystal, researchers said.

Study authors say much work needs to be done to understand the forces that cause these particles to move and combine. It is a frontier for new research.

"Particle pathways are tricky because they can form what appear to be crystals with the traditional faceted surfaces or they can have completely unexpected shapes and chemical compositions," said Dove, the corresponding author of the study and a member of the National Academy of Sciences. "Our group synthesized the evidence to show these pathways to growing a crystal become possible because of interplays between of thermodynamic and kinetic factors."

By understanding how animals form crystals into the working structures known as shells, teeth, and bones, scientists will have a bigger toolbox for interpreting the crystals formed in nature.

The insights may also help in the design of novel materials and explain unusual mineral patterns in rocks.

Likewise, knowing how pollutants are transported or trapped in the minerals of sediments has implications for environmental management of water and soil.

"How we think about the ways to crystallization impacts how we interpret natural crystallization processes in geochemical and biological environments, as well as how we design and control synthetic crystal growth processes," said De Yoreo. "I was surprised at how widespread a phenomenon particle-mediated crystallization is and how easily one can create a unified picture that captures its many styles."

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the Council on Geosciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division.

IgA deficiency is one of the most common genetic immunodeficiency disorders in humans and is associated with an insufficiency or complete absence of the antibody IgA. Researchers led from Uppsala University and Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have now performed the first comparative genetic study of IgA deficiency by using the dog as genetic disease model. Novel candidate genes have been identified and the results are published in PLOS ONE.

People with low IgA are at higher risk for developing recurrent infections, allergies and autoimmunity. The underlying genetic factors ...

Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) has helped millions survive the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Unfortunately, HIV has a built-in survival mechanism, creating reservoirs of latent, inactive virus that are invisible to both HAART and the immune system.

But now, researchers at UC Davis have identified a compound that activates latent HIV, offering the tantalizing possibility that the virus can be flushed out of the silent reservoirs and fully cured. Even better, the compound (PEP005) is already approved by the FDA. The study was published in the journal ...

(SEOUL and BOSTON) - The concept of walking on water might sound supernatural, but in fact it is a quite natural phenomenon. Many small living creatures leverage water's surface tension to maneuver themselves around. One of the most complex maneuvers, jumping on water, is achieved by a species of semi-aquatic insects called water striders that not only skim along water's surface but also generate enough upward thrust with their legs to launch themselves airborne from it.

Now, emulating this natural form of water-based locomotion, an international team of scientists from ...

A study by researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Duke University helps explain why the candidate vaccine used in the HVTN 505 clinical trial was not protective against HIV infection despite robustly inducing anti-HIV antibodies: the vaccine stimulated antibodies that recognized HIV as well as microbes commonly found in the intestinal tract, part of the body's microbiome. The researchers suggest that these antibodies arose because the vaccine boosted an existing antibody response to the intestinal microbiome, which may explain why ...

Washington -- Thousands of nonhuman primates continue to be confined alone in laboratories despite 30-year-old federal regulations and guidelines mandating that social housing of primates should be the default. A new article co-authored by PETA scientists and Marymount University researchers, published in Perspectives in Laboratory Animal Science, argues that many laboratories cage primates alone--a harmful practice often done for convenience--and that the U.S. government isn't doing enough to address this growing problem.

Decades of research shows that housing highly ...

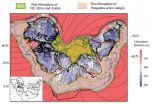

Boulder, Colo., USA - Two hundred and fifty million years ago, all the major continents were joined together, forming a continent called Pangea (which means "all land" in Greek). The plate thickness of continents can now be measured using seismology, and it is surprisingly variable, from about 90 km beneath places like California or Western Europe, to more than 200 km beneath the older interiors of the U.S., Eastern Europe, and Russia.

Authors Dan McKenzie, Michael C. Daly, and Keith Priestley wondered what the pattern of plate thickness looked like before Pangea broke ...

190 million Americans share the luxuries of human life with their pets. Giving dogs and cats a place in human homes, beds and--sometimes even, their wills--comes with the family member package.

Amongst these shared human-pet comforts is the unique luxury to overeat. As a result, the most common form of malnutrition for Americans and their companion animals results not from the underconsumption, but the overconsumption of food. The obesity epidemic also causes a similar array of diseases in people and pets: diabetes, hyperlipidemia and cancer.

During this year's ADSA-ASAS ...

Do you ever notice how stress and mental frustration can affect your physical abilities? When you are worried about something at work, do you find yourself more exhausted at the end of the day? This phenomenon is a result of the activation of a specific area of the brain when we attempt to participate in both physical and mental tasks simultaneously.

Ranjana Mehta, Ph.D., assistant professor at the Texas A&M Health Science Center School of Public Health, conducted a study evaluating the interaction between physical and mental fatigue and brain behavior.

The study showed ...

North of the Aleutian Islands, submarine canyons in the cold waters of the eastern Bering Sea contain a highly productive "green belt" that is home to deep-water corals as well as a plethora of fish and marine mammals.

Situated along the continental slope, the area also supports a thriving -- but potentially environmentally damaging -- bottom-trawling fishing industry that uses large weighted nets dragged across the seafloor to scoop up everything in their path.

A new study, conducted by research biologist Robert Miller of UC Santa Barbara's Marine Science Institute ...

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Two key physical phenomena take place at the surfaces of materials: catalysis and wetting. A catalyst enhances the rate of chemical reactions; wetting refers to how liquids spread across a surface.

Now researchers at MIT and other institutions have found that these two processes, which had been considered unrelated, are in fact closely linked. The discovery could make it easier to find new catalysts for particular applications, among other potential benefits.

"What's really exciting is that we've been able to connect atomic-level interactions of water ...