(Press-News.org) New brain research has mapped a key trouble spot likely to contribute to intellectual disability in Down syndrome. In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience [3 Aug], scientists from the University of Bristol and UCL suggest the findings could be used to inform future therapies which normalise the function of disrupted brain networks in the condition.

Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, and is triggered by an extra copy of chromosome 21. These findings shed new light on precisely which part of the brain's vast neural network contribute to problems in learning and memory in Down syndrome which until now, have remained unclear.

Using genetically engineered mice that carry a copy of this additional human chromosome, the researchers showed that increased expression of chromosome 21 genes disrupts the function of key brain circuits involved in learning and memory.

Processing of information in the brain requires accurately coordinated communication between networks of nerve cells, which are wired together in electrical circuits by junctions called synapses. Using high-tech microscopy, nerve cell recordings and maze testing, the researchers showed abnormal structure and function of synapses in the networks of the hippocampus in the mouse model of Down syndrome.

The hippocampus acts as a central hub for learning and memory, allowing us to integrate our past experience with our current context. These functions are underpinned by 'place cells' -- cells that act like the brain's GPS and form maps of our environment (Professor John O'Keefe, of UCL, was awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize for his discovery of these cells).

This latest study shows that dysfunction at the input synapses of the hippocampus propagates around hippocampal circuits in the mouse model of Down syndrome, resulting in unstable information processing by place cells and impaired learning and memory. Over the course of a lifetime, even subtle impairments of this type will profoundly influence intellectual abilities.

Dr Matt Jones, lead author of the study and MRC Senior Research Fellow at the School of Physiology and Pharmacology at the University of Bristol, said: "Abnormalities in the hippocampus have been shown before in other mouse models of Down syndrome, but the mouse model we used is a more accurate genetic mimic of the human syndrome. The wiring diagram of the brain is so massively interconnected, we need to consider how even subtle changes in one part of the brain can cause trouble for other nodes of the circuit."

Dr Jonathan Witton, one of the study's main authors and also of Bristol's School of Physiology and Pharmacology, added: "This study further highlights the vulnerability of the hippocampus to increased expression of chromosome 21 genes. Therapies which aim to normalise the function of these disrupted networks may be particularly beneficial as part of the future treatments of Down syndrome."

Professor Elizabeth Fisher of UCL, who made the mouse model with Dr Victor Tybulewicz of the Francis Crick Institute, said: "It is very important that we work in the most effective and collaborative way to understand what is happening in these mice, so we further our knowledge of human Down syndrome for possible future therapies."

The collaborative study, funded by the Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council (MRC), involved researchers from the University of Bristol, UCL, Open University, University of Oxford, and the Francis Crick Institute, London.

Paper

Hippocampal circuit dysfunction in the Tc1 mouse model of Down syndrome by J Witton et al in Nature Neuroscience.

Trouble spot in brain linked to learning difficulties in Down syndrome identified

2015-08-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

CO2 removal cannot save the oceans -- if we pursue business as usual

2015-08-03

Greenhouse-gas emissions from human activities do not only cause rapid warming of the seas, but also ocean acidification at an unprecedented rate. Artificial carbon dioxide removal (CDR) from the atmosphere has been proposed to reduce both risks to marine life. A new study based on computer calculations now shows that this strategy would not work if applied too late. CDR cannot compensate for soaring business-as-usual emissions throughout the century and beyond, even if the atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration would be restored to pre-industrial levels at some ...

NYSCF Global Stem Cell ArrayTM brings precision medicine one step closer to the clinic

2015-08-03

NEW YORK, NY (August 3, 2015) - Scientists at The New York Stem Cell Foundation (NYSCF) Research Institute successfully designed a revolutionary, high-throughput, robotic platform that automates and standardizes the process of transforming patient samples into stem cells. This unique platform, the NYSCF Global Stem Cell ArrayTM, for the first time gives researchers the scale to look at diverse populations to better understand the underlying causes of disease and create new individually tailored treatments, enabling precision medicine in patient care.

A paper published ...

Character traits outweigh material benefits in assessing value others bring us

2015-08-03

When it comes to making decisions involving others, the impression we have of their character weighs more heavily than do our assessments of how they can benefit us, a team of New York University researchers has found.

"When we learn and make decisions about people, we don't simply look at the positive or negative outcomes they bring to us--such as whether they gave us a loan or helped us move," explains Leor Hackel, a doctoral candidate in NYU's Department of Psychology and the study's lead author. "Instead, we often look beyond concrete outcomes to form trait impressions, ...

Fly brains filter out visual information caused by their own movements, like humans

2015-08-03

Our brains are constantly barraged with sensory information, but have an amazing ability to filter out just what they need to understand what's going on around us. For instance, if you stand perfectly still in a room, and that room rotates around you, it's terrifying. But stand still in a room and turn your eyes, and the same visual input feels perfectly normal. That's thanks to a complex process in our brain that tell us when and how to pay attention to sensory input. Specifically, we ignore visual input caused by our own eye movements.

Now, researchers at The Rockefeller ...

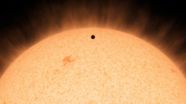

Cassiopeia's hidden gem: The closest rocky, transiting planet

2015-08-03

Skygazers at northern latitudes are familiar with the W-shaped star pattern of Cassiopeia the Queen. This circumpolar constellation is visible year-round near the North Star. Tucked next to one leg of the W lies a modest 5th-magnitude star named HD 219134 that has been hiding a secret.

Astronomers have now teased out that secret: a planet in a 3-day orbit that transits, or crosses in front of its star. At a distance of just 21 light-years, it is by far the closest transiting planet to Earth, which makes it ideal for follow-up studies. Moreover, it is the nearest rocky ...

Shifting winds, ocean currents doubled endangered Galápagos penguin population

2015-08-03

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Shifts in trade winds and ocean currents powered a resurgence of endangered Galápagos penguins over the past 30 years, according to a new study. These changes enlarged a cold pool of water the penguins rely on for food and breeding - an expansion that could continue as the climate changes over the coming decades, the study's authors said.

The Galápagos Islands, a chain of islands 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) west of mainland Ecuador, are home to the only penguins in the Northern Hemisphere. The 48-centimeter (19-inch) tall black and white ...

The uneasy, unbreakable link of money, medicine

2015-08-03

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Even after centuries of earnest oaths and laws, the debate about whether money compromises medicine remains unresolved, observes Dr. Eli Adashi in a new paper in the AMA Journal of Ethics. The problem might not be truly intractable, he said, but recent reforms will likely make little progress or difference.

"This is one of those things we have to appreciate as being with us for a long time," said Adashi, former dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown University. "It will probably be with us forever. It's probably not entirely ...

Veterans returning from Middle East face higher skin cancer risk

2015-08-03

Soldiers who served in the glaring desert sunlight of Iraq and Afghanistan returned home with an increased risk of skin cancer, due not only to the desert climate, but also a lack of sun protection, Vanderbilt dermatologist Jennifer Powers, M.D., reports in a study published recently in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

"The past decade of United States combat missions, including operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, have occurred at a more equatorial latitude than the mean center of the United States population, increasing the potential for ultraviolet irradiance ...

New approach for making vaccines for deadly diseases

2015-08-03

PHILADELPHIA - Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have devised an entirely new approach to vaccines - creating immunity without vaccination.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, demonstrated that animals injected with synthetic DNA engineered to encode a specific neutralizing antibody against the dengue virus were capable of producing the exact antibodies necessary to protect against disease, without the need for standard antigen-based vaccination. Importantly, this approach, termed DMAb, was rapid, protecting animals ...

When farm to table means crossing international borders

2015-08-03

With Congress currently debating the repeal of mandatory country-of-origin labeling (COOL) for meat and poultry - federal law in the US since 2002 - new research from the Sam W. Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas shines a spotlight on how COOL labeling affects consumers' purchase decisions.

In "A COOL Effect: The Direct and Indirect Impact of Country-of-Origin Disclosures on Purchase Intentions for Retail Food Products," appearing in the September issue of the Journal of Retailing, Marketing Professors Elizabeth Howlett and Scot Burton, along with ...