New insight into how the immune system sounds the alarm

2015-08-03

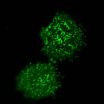

(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA--T cells are the guardians of our bodies: they constantly search for harmful invaders and diseased cells, ready to swarm and kill off any threats. A better understanding of these watchful sentries could allow scientists to boost the immune response against evasive dangers (e.g., cancer or infections), or to silence it when it mistakenly attacks the body itself (e.g., autoimmune disorders or allergies).

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered that T cell triggering relies on a dynamic protein network at the cell surface, as reported in August 3, 2015, in Nature Immunology.

"This is a completely new principle for how T cell activity is controlled--whether it ignores or responds to a threat," says senior author Björn Lillemeier, an assistant professor in the Nomis Foundation Laboratories for Immunobiology and Microbial Pathogenesis and the Waitt Advanced Biophotonics Center at the Salk Institute.

T cells become active when a signal--often from a virus or bacterium--triggers molecular sensors on their surface, namely T cell receptors. Previously, scientists believed that additional molecules that bind T cell receptors and help it to perceive this signal were like grapes hanging from a vine, occasionally dropping away or joining to begin the process. In contrast, the new discovery shows that T cell receptors are incredibly active--more like a bustling train station, with molecules rapidly coming and going at different intervals of time, says Lillemeier, who is also the Helen McLoraine Developmental Chair.

A protein called ZAP-70 is well known as a crucial player for kicking the T cell into action. Until now, scientists assumed that a silent form of ZAP-70 floats around inside the T cell until a threat is detected, which recruits ZAP-70 to the cell surface and activates it. By analyzing mutant forms of ZAP-70, Lillemeier's group discovered that instead of ZAP-70 binding the T cell receptor firmly, it comes in contact with the receptor sporadically. Each time this happens, ZAP-70 has to adopt an unfavorable shape that forces it back inside the cell. This cycle continues until a second molecule, called Lck, helps it to remain with the T cell receptor. The prolonged stay at the cell surface activates ZAP-70 and prompts the T cell to attack invaders and diseased cells.

This study shows that the steps underlying T cell activation are much more dynamic compared with the less mobile modes that scientists had suspected before. The new study highlights how ZAP-70 and other molecules communicate in space and time, which is crucial for controlling the ultimate activity of a T cell. By understanding this process, Lillemeier says, "We might be able to encourage the immune system to be a little more sensitive in order to recognize and eliminate diseases."

Lillemeier's team is working to identify new principles that determine if T cells respond to a threat versus staying quiet. In addition, they are testing whether their findings could be applied across additional processes in T cells and other immune cells. Because proteins have many of the same modular building blocks, in principle, any protein with structural characteristics comparable to those of ZAP-70 could be controlled by similar mechanisms, Lillemeier says.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the study were Christian Klamm, Lucie Novotná, Dongyang Li, Miriam Wolf, and Amy Blount of Salk's Nomis Center for Immunobiology and Microbial Pathogenesis and the Waitt Advanced Biophotonics Center; and Kai Zhang and Jonathan Fitchett of Eli Lilly's Lilly Biotechnology Center in San Diego.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health, the Nomis Foundation, the Waitt Foundation and the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-08-03

New brain research has mapped a key trouble spot likely to contribute to intellectual disability in Down syndrome. In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience [3 Aug], scientists from the University of Bristol and UCL suggest the findings could be used to inform future therapies which normalise the function of disrupted brain networks in the condition.

Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, and is triggered by an extra copy of chromosome 21. These findings shed new light on precisely which part of the brain's vast neural network contribute ...

2015-08-03

Greenhouse-gas emissions from human activities do not only cause rapid warming of the seas, but also ocean acidification at an unprecedented rate. Artificial carbon dioxide removal (CDR) from the atmosphere has been proposed to reduce both risks to marine life. A new study based on computer calculations now shows that this strategy would not work if applied too late. CDR cannot compensate for soaring business-as-usual emissions throughout the century and beyond, even if the atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration would be restored to pre-industrial levels at some ...

2015-08-03

NEW YORK, NY (August 3, 2015) - Scientists at The New York Stem Cell Foundation (NYSCF) Research Institute successfully designed a revolutionary, high-throughput, robotic platform that automates and standardizes the process of transforming patient samples into stem cells. This unique platform, the NYSCF Global Stem Cell ArrayTM, for the first time gives researchers the scale to look at diverse populations to better understand the underlying causes of disease and create new individually tailored treatments, enabling precision medicine in patient care.

A paper published ...

2015-08-03

When it comes to making decisions involving others, the impression we have of their character weighs more heavily than do our assessments of how they can benefit us, a team of New York University researchers has found.

"When we learn and make decisions about people, we don't simply look at the positive or negative outcomes they bring to us--such as whether they gave us a loan or helped us move," explains Leor Hackel, a doctoral candidate in NYU's Department of Psychology and the study's lead author. "Instead, we often look beyond concrete outcomes to form trait impressions, ...

2015-08-03

Our brains are constantly barraged with sensory information, but have an amazing ability to filter out just what they need to understand what's going on around us. For instance, if you stand perfectly still in a room, and that room rotates around you, it's terrifying. But stand still in a room and turn your eyes, and the same visual input feels perfectly normal. That's thanks to a complex process in our brain that tell us when and how to pay attention to sensory input. Specifically, we ignore visual input caused by our own eye movements.

Now, researchers at The Rockefeller ...

2015-08-03

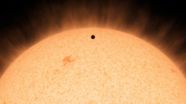

Skygazers at northern latitudes are familiar with the W-shaped star pattern of Cassiopeia the Queen. This circumpolar constellation is visible year-round near the North Star. Tucked next to one leg of the W lies a modest 5th-magnitude star named HD 219134 that has been hiding a secret.

Astronomers have now teased out that secret: a planet in a 3-day orbit that transits, or crosses in front of its star. At a distance of just 21 light-years, it is by far the closest transiting planet to Earth, which makes it ideal for follow-up studies. Moreover, it is the nearest rocky ...

2015-08-03

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Shifts in trade winds and ocean currents powered a resurgence of endangered Galápagos penguins over the past 30 years, according to a new study. These changes enlarged a cold pool of water the penguins rely on for food and breeding - an expansion that could continue as the climate changes over the coming decades, the study's authors said.

The Galápagos Islands, a chain of islands 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) west of mainland Ecuador, are home to the only penguins in the Northern Hemisphere. The 48-centimeter (19-inch) tall black and white ...

2015-08-03

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Even after centuries of earnest oaths and laws, the debate about whether money compromises medicine remains unresolved, observes Dr. Eli Adashi in a new paper in the AMA Journal of Ethics. The problem might not be truly intractable, he said, but recent reforms will likely make little progress or difference.

"This is one of those things we have to appreciate as being with us for a long time," said Adashi, former dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown University. "It will probably be with us forever. It's probably not entirely ...

2015-08-03

Soldiers who served in the glaring desert sunlight of Iraq and Afghanistan returned home with an increased risk of skin cancer, due not only to the desert climate, but also a lack of sun protection, Vanderbilt dermatologist Jennifer Powers, M.D., reports in a study published recently in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

"The past decade of United States combat missions, including operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, have occurred at a more equatorial latitude than the mean center of the United States population, increasing the potential for ultraviolet irradiance ...

2015-08-03

PHILADELPHIA - Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have devised an entirely new approach to vaccines - creating immunity without vaccination.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, demonstrated that animals injected with synthetic DNA engineered to encode a specific neutralizing antibody against the dengue virus were capable of producing the exact antibodies necessary to protect against disease, without the need for standard antigen-based vaccination. Importantly, this approach, termed DMAb, was rapid, protecting animals ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New insight into how the immune system sounds the alarm