(Press-News.org) Dogs have a specialized region in their brains for processing faces, a new study finds. PeerJ is publishing the research, which provides the first evidence for a face-selective region in the temporal cortex of dogs.

"Our findings show that dogs have an innate way to process faces in their brains, a quality that has previously only been well-documented in humans and other primates," says Gregory Berns, a neuroscientist at Emory University and the senior author of the study.

Having neural machinery dedicated to face processing suggests that this ability is hard-wired through cognitive evolution, Berns says, and may help explain dogs' extreme sensitivity to human social cues.

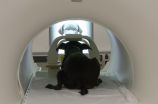

Berns heads up the Dog Project in Emory's Department of Psychology, which is researching evolutionary questions surrounding man's best, and oldest, friend. The project was the first to train dogs to voluntarily enter a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner and remain motionless during scanning, without restraint or sedation.

In previous research, the Dog Project identified the caudate region of the canine brain as a reward center. It also showed how that region of a dog's brain responds more strongly to the scents of familiar humans than to the scents of other humans, or even to those of familiar dogs.

For the current study, the researchers focused on how dogs respond to faces versus everyday objects. "Dogs are obviously highly social animals," Berns says, "so it makes sense that they would respond to faces. We wanted to know whether that response is learned or innate."

The study involved dogs viewing both static images and video images on a screen while undergoing fMRI. It was a particularly challenging experiment since dogs do not normally interact with two-dimensional images, and they had to undergo training to learn to pay attention to the screen.

A limitation of the study was the small sample size: Only six of the eight dogs enrolled in the study were able to hold a gaze for at least 30 seconds on each of the images to meet the experimental criteria.

The results were clear, however, for the six subjects able to complete the experiment. A region in their temporal lobe responded significantly more to movies of human faces than to movies of everyday objects. This same region responded similarly to still images of human faces and dog faces, yet significantly more to both human and dog faces than to images of everyday objects.

If the dogs' response to faces was learned - by associating a human face with food, for example - you would expect to see a response in the reward system of their brains, but that was not the case, Berns says.

A previous study, decades ago, using electrophysiology, found several face-selective neurons in sheep.

"That study identified only a few face-selective cells and not an entire region of the cortex," says Daniel Dilks, an Emory assistant professor of psychology and the first author of the current dog study.

The researchers have dubbed the canine face-processing region they identified the dog face area, or DFA.

Humans have at least three face processing regions in the brain, including the fusiform face area, or FFA, which is associated with distinguishing faces from other objects. "We can predict what parts of your brain are going to be activated when you're looking at faces," Dilks says. "This is incredibly reliable across people."

One hypothesis is that distinguishing faces is important for any social creature.

"Dogs have been cohabitating with humans for longer than any other animal," Dilks says. "They are incredibly social, not just with other members of their pack, but across species. Understanding more about canine cognition and perception may tell us more about social cognition and perception in general."

INFORMATION:

Trauma may cause distinct and long-lasting effects even in people who do not develop PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), according to research by scientists working at the University of Oxford's Department of Psychiatry. It is already known that stress affects brain function and may lead to PTSD, but until now the underlying brain networks have proven elusive.

Led by Prof Morten Kringelbach, the Oxford team's systematic meta-analysis of all brain research on PTSD is published in the journal Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews. The research is part of a larger ...

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA (AUGUST 4, 2015). Researchers at the University of Virginia (UVa) examined the number and severity of subconcussive head impacts sustained by college football players over an entire season during practices and games. The researchers found that the number of head impacts varied depending on the intensity of the activity. Findings in this case are reported and discussed in "Practice type effects on head impact in collegiate football," by Bryson B. Reynolds and colleagues, published today online, ahead of print, in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The researchers ...

August 4, 2015 -- Treating maternal psychiatric disorder with commonly used antidepressants is associated with a lower risk of certain pregnancy complications including preterm birth and delivery by Caesarean section, according to researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University Medical Center, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute. However, the medications -- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs -- resulted in an increased risk of neonatal problems. Findings are published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

"To ...

Chestnut Hill, MA (August 4, 2015): It's been said that "Those who don't know history are doomed to repeat it," but even if you know your own history, that doesn't necessarily help you with self-control. New research published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology shows the effectiveness of memory in improving our everyday self-control decisions depends on what we recall and how easily it comes to mind.

"Despite the common belief that remembering our mistakes will help us make better decisions in the present," says the study's lead author, Hristina Nikolova, Ph.D., an ...

PHILADELPHIA - The roughly nine million Americans who rely on prescription sleeping pills to treat chronic insomnia may be able to get relief from as little as half of the drugs, and may even be helped by taking placebos in the treatment plan, according to new research published today in the journal Sleep Medicine by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Their findings starkly contrast with the standard prescribing practices for chronic insomnia treatment.

The findings, which advocate for a dosing strategy of smaller and fewer ...

Research on alcohol-use disorders consistently shows problem drinking decreases as we age. Also called, "maturing out," these changes generally begin during young adulthood and are partially caused by the roles we take on as we become adults. Now, researchers collaborating between the University of Missouri and Arizona State University have found evidence that marriage can cause dramatic drinking reductions even among people with severe drinking problems. Scientists believe findings could help improve clinical efforts to help these people, inform public health policy changes ...

Here's a quick task: Take a look at the sentences below and decide which is the most effective.

(1) "John threw out the old trash sitting in the kitchen."

(2) "John threw the old trash sitting in the kitchen out."

Either sentence is grammatically acceptable, but you probably found the first one to be more natural. Why? Perhaps because of the placement of the word "out," which seems to fit better in the middle of this word sequence than the end.

In technical terms, the first sentence has a shorter "dependency length" -- a shorter total distance, in words, between ...

To arrange for an interview with a researcher, please contact the Communications staff member identified at the end of each tip. For more information on ORNL and its research and development activities, please refer to one of our media contacts. If you have a general media-related question or comment, you can send it to news@ornl.gov.

CYBERSECURITY - Piranha nets honor ...

Piranha, an award-winning intelligent agent-based technology to analyze text data with unprecedented speed and accuracy, will be showcased at the Smithsonian's Innovation Festival Sept. 26-27. The ...

Many people who are skeptical about vaccinating their children can be convinced to do so, but only if the argument is presented in a certain way, a team of psychologists from UCLA and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign reported today. The research appears in the online early edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The finding is especially important because the number of measles cases in the U.S. tripled from 2013 to 2014. The disease's re-emergence has been linked to a trend of parents refusing to vaccinate their children.

What ...

Like top musicians, songbirds train from a young age to weed out errors and trim variability from their songs, ultimately becoming consistent and reliable performers. But as with human musicians, even the best are not machines. To learn and improve, the songbird brain needs to shake up its tried-and-true patterns with a healthy dose of creative experimentation. Until now, no one has found a specific mechanism by which this could occur.

Now, researchers at UC San Francisco have discovered a neurological mechanism that could explain how songbirds' neural creativity-generator ...