The study could help with the development of new agricultural techniques for protecting cereal crops from infection. Barley grains are the basis of many staple foods, and also central to the brewing and malting industries, so keeping the plants disease-free is becoming increasingly important for food security. Today's research, led by Dr Pietro Spanu from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, decodes the genome of Blumeria, which causes powdery mildew on barley.

Powdery mildew affects a wide range of fruit, vegetable and cereal crops in northern Europe. Infected plants become covered in powdery white spots that spread all over the leaves and stems, preventing them from producing crops, and having a devastating impact on the overall agricultural yield. Farmers use fungicides, genetically resistant varieties and crop rotation to prevent mildew epidemics, but the fungi often evolve too rapidly for the techniques to be effective. The mildew is able to evolve so quickly because multiple parasites within the genome, known as 'transposons', help it to disguise itself and go unrecognised by the plant's defences. It is as if the transposons confuse the host plant by changing the target molecules that the plant uses to detect the onset of disease.

The researchers discovered that Blumeria had unusually large numbers of transposons within it. "It was a big surprise," said Dr Spanu, "as a genome normally tries to keep its transposons under control. But in these genomes, one of the controls has been lifted. We think it might be an adaptive advantage for them to have these genomic parasites, as it allows the pathogens to respond more rapidly to the plant's evolution and defeat the immune system."

The authors believe that their research will contribute significantly to the design of new fungicides and resistance in food crops, as they now understand how the mildew can adapt so quickly. "With this knowledge of the genome we can now rapidly identify which genes have mutated, and then can select plant varieties that are more resistant," said Dr Spanu. The genetic codes will also help scientists monitor the spread and evolution of fungicide resistance in an emerging epidemic. "We'll be able to develop more efficient ways to monitor and understand the emergence of resistance, and ultimately to design more effective and durable control measures."

Mildew pathogens are a type of 'obligate' parasite, which means they are completely dependent on their plant hosts to survive, and cannot live freely in the soil. Because they are so dependent, the pathogens have devised a way to disguise themselves in order to avoid the immune response of the host plant and overcome its defences.

"We've now found this happening in lots of fungi and fungal-like organisms that are obligate pathogens," said Dr Spanu, adding that the costly genome inflation could therefore be a trade-off that makes these pathogens successful. "Non-obligate pathogens are not so dependent on their hosts, as they can live elsewhere," said Dr Spanu, "so they are less dependent on rapid evolution."

INFORMATION: The study was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Max Planck Society and the Institut Nationale de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA).

For further information please contact:

Laura Gallagher

Research Media Relations Manager

Imperial College London

email: l.gallagher@imperial.ac.uk

Tel: +44(0)20 7594 8432

Out of hours duty press officer: +44(0)7803 886 248

Notes to editors:

1. Genome expansion and gene loss in powdery mildew fungi reveal functional tradeoffs in extreme parasitism. As published in Science, 10 December 2010. For a full list of authors please refer to the paper.

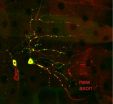

2. Images: Image showing the powdery mildew and its intracellular feeding structure. Credit: Pietro Spanu. Mildewed barley leaf: this highly infectious disease will make short-shrift of it victim. No significant grain will be produced if this plant were not protected by effective immunity or sophisticated fungicides. Credit: Pietro Spanu. The mildew spores (the cigar-shaped oblong structure) can travel hundreds of miles on the wind and spread disease within days. Once on the plant epidermis, they germinate within minutes to produce first a sensing device (the small primary germtube) and then a larger secondary gem-tube devoted to drill into the host cell. Credit: Pietro Spanu. Epidermal plant cells (outlined in yellow) are extensively colonised by the parasite (green), which effectively turn off all recognition devices and keep the plant alive for the duration of the infection, enabling the mildew to take up food and produce more spores for further dissemination. Credit: Pietro Spanu. Same as 4) but with different colouring A phylogenetic tree illustrating the sequence similarities of powdery mildew genes though to encode "effectors": proteins devoted to subverting host immunity and metabolism for the mildews' own benefit. Credit: Pietro Spanu.

3. The Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) is the UK funding agency for research in the life sciences. Sponsored by Government, BBSRC annually invests around £470M in a wide range of research that makes a significant contribution to the quality of life in the UK and beyond and supports a number of important industrial stakeholders, including the agriculture, food, chemical, healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors. BBSRC provides institute strategic research grants to the following: The Babraham Institute, Institute for Animal Health, Institute for Biological, Environmental and Rural Studies (Aberystwyth University), Institute of Food Research , John Innes Centre , The Genome Analysis Centre, The Roslin Institute (University of Edinburgh), Rothamsted Research. The Institutes conduct long-term, mission-oriented research using specialist facilities. They have strong interactions with industry, Government departments and other end-users of their research. Website: www.bbsrc.ac.uk

4. The research institutes of the Max Planck Society perform basic research in the interest of the general public in the natural sciences, life sciences, social sciences, and the humanities. In particular, the Max Planck Society takes up new and innovative research areas that German universities are not in a position to accommodate or deal with adequately. These interdisciplinary research areas often do not fit into the university organization, or they require more funds for personnel and equipment than those available at universities. The variety of topics in the natural sciences and the humanities at Max Planck Institutes complement the work done at universities and other research facilities in important research fields. In certain areas, the institutes occupy key positions, while other institutes complement ongoing research. Moreover, some institutes perform service functions for research performed at universities by providing equipment and facilities to a wide range of scientists, such as telescopes, large-scale equipment, specialized libraries, and documentary resources. Website: www.mpg.de

5. Institut Nationale de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA) is the leading European agricultural research institute and one of the foremost institutes in the world for agriculture, food and the environment. It is also the second largest public research institute in France. Founded in 1946, the National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) is a mission-oriented public research institution under the joint authority of the Ministry of Higher Education and Research and the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. The research conducted at INRA concerns agriculture, food, nutrition and food safety, environment and land management, with particular emphasis on sustainable development. Website: www.inra.fr

6. About Imperial College London: Consistently rated amongst the world's best universities, Imperial College London is a science-based institution with a reputation for excellence in teaching and research that attracts 14,000 students and 6,000 staff of the highest international quality. Innovative research at the College explores the interface between science, medicine, engineering and business, delivering practical solutions that improve quality of life and the environment - underpinned by a dynamic enterprise culture.

Since its foundation in 1907, Imperial's contributions to society have included the discovery of penicillin, the development of holography and the foundations of fibre optics. This commitment to the application of research for the benefit of all continues today, with current focuses including interdisciplinary collaborations to improve global health, tackle climate change, develop sustainable sources of energy and address security challenges. In 2007, Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust formed the UK's first Academic Health Science Centre. This unique partnership aims to improve the quality of life of patients and populations by taking new discoveries and translating them into new therapies as quickly as possible. Website: www.imperial.ac.uk