Whistled Turkish challenges notions about language and the brain

2015-08-17

(Press-News.org) Generally speaking, language processing is a job for the brain's left hemisphere. That's true whether that language is spoken, written, or signed. But researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on August 17 have discovered an exception to this rule in a most remarkable form: whistled Turkish.

"We are unbelievably lucky that such a language indeed exists," says Onur Güntürkün of Ruhr-University Bochum in Germany. "It is a true experiment of nature."

Whistled Turkish is exactly what it sounds like: Turkish that has been adapted into a series of whistles. This method of communicating was popular in the old days, before the advent of telephones, in small villages in Turkey as a means for long-distance communication. In comparison to spoken Turkish, whistled Turkish carries much farther. While whistled-Turkish speakers use "normal" Turkish at close range, they switch to the whistled form when at a distance of, say, 50 to 90 meters away.

"If you look at the topography, it is clear how handy whistled communication is," Güntürkün says. "You can't articulate as loud as you can whistle, so whistled language can be heard kilometers away across steep canyons and high mountains."

Whistled Turkish isn't a distinct language from Turkish, Güntürkün explains. It is Turkish converted into a different form, much as the text you are now reading is English converted into written form. Güntürkün, who is Turkish, says that he still found the language surprisingly difficult to understand.

"As a native Turkish-speaking person, I was struck that I did not understand a single word when these guys started whistling," he says. "Not one word! After about a week, I started recognizing a few words, but only if I knew the context."

Whistled Turkish is clearly fascinating in its own right, but Güntürkün and his colleagues also realized that it presented a perfect opportunity to test the notion that language is predominantly a left-brained activity, no matter the physical structure that it takes. That's because auditory processing of features, including frequency, pitch, and melody--the stuff that whistles are made of--is a job for the right brain.

The researchers examined the brain asymmetry in processing spoken versus whistled Turkish by presenting whistled-Turkish speakers with speech sounds delivered to their left or right ears through headphones. The participants then reported what they'd heard. While individuals more often perceived spoken syllables when presented to the right ear, they heard whistled sounds equally well on both sides.

"We could show that whistled Turkish creates a balanced contribution of the hemispheres," Güntürkün says. "The left hemisphere is involved since whistled Turkish is a language, but the right hemisphere is equally involved since for this strange language all auditory specializations of this hemisphere are needed."

That's important, the researchers say, because it means that the left-hemispheric dominance in language does depend on the physical structure the language takes. They now plan to conduct EEG studies to look even more closely at the underlying brain processes in whistled-Turkish speakers.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Current Biology, Güntürkün et al.: "Whistled Turkish alters language asymmetries" http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.067

Current Biology, published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that features papers across all areas of biology. Current Biology strives to foster communication across fields of biology, both by publishing important findings of general interest and through highly accessible front matter for non-specialists. For more information please visit http://www.cell.com/current-biology. To receive media alerts for Current Biology or other Cell Press journals, contact press@cell.com.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-08-17

Health care is a major responsibility of Canada's federal government and must be a key issue in the fall election, argues Dr. Matthew Stanbrook in an editorial in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"The federal government seems to be trying to get itself out of the health care business," states Dr. Stanbrook, deputy editor, CMAJ. "It cannot. Many essential aspects of health care are a federal responsibility, and our biggest, most complex problems in the health care system cannot be solved without federal leadership."

He argues that over most of the last 10 ...

2015-08-17

Nearly 2 million people throughout the Great Plains and California above aquifer sites contaminated with natural uranium that is mobilized by human-contributed nitrate, according to a study from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Data from roughly 275,000 groundwater samples in the High Plains and Central Valley aquifers show that many Americans live less than two-thirds of a mile from wells that often far exceed the uranium guideline set by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The study reports that 78 percent of the uranium-contaminated sites were linked to the ...

2015-08-17

Philadelphia, PA, August 17, 2015 -- Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), a type of IV typically inserted in a vein in the arm, are frequently used by healthcare professionals to obtain long-term central venous access in hospitalized patients. While there are numerous benefits associated with PICCs, a potential complication is deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or blood clots, in upper limbs. A new study of more than 70,000 patients in 48 Michigan hospitals indicates that PICC use is associated not only with upper-extremity DVT, but also with lower-extremity DVT. The ...

2015-08-17

CORVALLIS, Ore. - More than 20 million years ago, a short struggle took place in what is now the Dominican Republic, resulting in one animal getting its leg bitten off by a predator just before it escaped. But in the confusion, it fell into a gooey resin deposit, to be fossilized and entombed forever in amber.

The fossil record of that event has revealed something not known before - that salamanders once lived on an island in the Caribbean Sea. Today, they are nowhere to be found in the entire Caribbean area.

The never-before-seen and now extinct species of salamander, ...

2015-08-17

Irvine, Calif., August 17, 2015 - A woman's weight at birth, education level and marital status pre-pregnancy can have repercussions for two generations, putting her children and grandchildren at higher risk of low birth weight, according to a new study by Jennifer B. Kane, assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Irvine. The findings are the first to tie social and biological factors together using population data in determining causes for low birth weight.

"We know that low-birth-weight babies are more susceptible to later physical and cognitive ...

2015-08-17

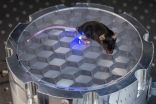

A miniature device that combines optogenetics - using light to control the activity of the brain - with a newly developed technique for wirelessly powering implanted devices is the first fully internal method of delivering optogenetics.

The device dramatically expands the scope of research that can be carried out through optogenetics to include experiments involving mice in enclosed spaces or interacting freely with other animals. The work is published in the Aug. 17 edition of Nature Methods.

"This is a new way of delivering wireless power for optogenetics," said ...

2015-08-17

Two Florida laws, enacted to combat prescription drug abuse and misuse in that state, led to a small but significant decrease in the amount of opioids prescribed the first year the laws were in place, a new study by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers suggests.

One measure created a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, a database that tracks individual prescriptions, including patient names, dates and amounts prescribed, so physicians can be on the lookout for excesses associated with addiction and illicit use. Another addresses so-called "pill ...

2015-08-17

Children with parents or caregivers currently serving in the military had a higher prevalence of substance use, violence, harassment and weapon-carrying than their nonmilitary peers in a study of California school children, according to an article published online by JAMA Pediatrics.

While most young people whose families are connected to the military demonstrate resilience, war-related stressors, including separation from parents because of deployment, frequent relocation and the worry about future deployments, can contribute to struggles for some of them, according ...

2015-08-17

Menlo Park, Calif. -- Scientists have revealed never-before-seen details of how our brain sends rapid-fire messages between its cells. They mapped the 3-D atomic structure of a two-part protein complex that controls the release of signaling chemicals, called neurotransmitters, from brain cells. Understanding how cells release those signals in less than one-thousandth of a second could help launch a new wave of research on drugs for treating brain disorders.

The experiments, at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser at the Department of Energy's SLAC National ...

2015-08-17

Adversity during the first six years of life was associated with higher levels of childhood internalizing symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, in a group of boys, as well as altered brain structure in late adolescence between the ages of 18 and 21, according to an article published online by JAMA Pediatrics.

Both altered brain structure and an increased risk of developing internalizing symptoms have been associated with adversity early in life.

Edward D. Barker, Ph.D., of King's College London, and coauthors examined how adverse experiences within the first six ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Whistled Turkish challenges notions about language and the brain