(Press-News.org) University of Pennsylvania researchers have made strides toward a new method of gene sequencing a strand of DNA's bases are read as they are threaded through a nanoscopic hole.

In a new study, they have shown that this technique can also be applied to proteins as way to learn more about their structure.

Existing methods for this kind of analysis are labor intensive, typically entailing the collection of large quantities of the protein. They also often require modifying the protein, limiting these methods' usefulness for understanding the protein's behavior in its natural state.

The Penn researchers' translocation technique allows for the study of individual proteins without modifying them. Samples taken from a single individual could be analyzed this way, opening applications for disease diagnostics and research.

The study was led by Marija Drndi?, a professor in the School of Arts & Sciences' Department of Physics & Astronomy; David Niedzwiecki, a postdoctoral researcher in her lab; and Jeffery G. Saven, a professor in Penn Arts & Sciences' Department of Chemistry.

It was published in the journal ACS Nano.

The Penn team's technique stems from Drndi?'s work on nanopore gene sequencing, which aims to distinguish the bases in a strand of DNA by the different percent of the aperture they each block as they pass through a nanoscopic pore. Different silhouettes allow different amounts of an ionic liquid to pass through. The change in ion flow is measured by electronics surrounding the pore; the peaks and valleys of that signal can be correlated to each base.

While researchers work to increase the accuracy of these readings to useful levels, Drndi? and her colleagues have experimented with applying the technique to other biological molecules and nanoscale structures.

Collaborating with Saven's group, they set out to test their pores on even trickier biological molecules.

"There are many proteins that are much smaller and harder to manipulate than a strand of DNA that we'd like to study," Saven said. "We're interested in learning about the structure of a given protein, such as whether it exists as a monomer, or combined with another copy into a dimer, or an aggregate of multiple copies known as an oligomer."

Detection is also often a limitation.

"There are no ways to amplify peptides and proteins like there are for DNA," Drndi? said. "If you want to study proteins from a particular source, you're stuck with very small samples. With this method, however, you can just collect the amount of data you need and the number of proteins you want to pass through the pore and then study them one at a time as they naturally exist in the body."

Using the Drndi? group's silicon nitride nanopores, which can be drilled to custom diameters, the research team set out to test their technique on GCN4-p1, a protein selected because it contains a common structural motif found in transcription factors and intracellular receptors.

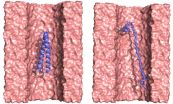

"The dimer version is 'zipped' together," Niedzwiecki said, "It is a 'coiled coil' of interleaved helices that is roughly cylindrical. The monomer version is unzipped and is likely not helical; it's probably more like a string."

The researchers put different ratios of zipped and unzipped versions of the protein in an ionic fluid and passed them through the pores. While unable to tell the difference between individual proteins, the researchers could perform this analysis on populations of the molecule.

"The dimer and monomer form of the protein block a different number of ions, so we see a different drop in current when they go through the pore," Niedzwiecki said. "But we get a range of values for both, as not every molecular translocation event is the same."

Determining whether a specific sample of these types of proteins are aggregating or not could be used to better understand the progression of disease.

"Many researchers," Saven said, "have observed these long tangles of aggregated peptides and proteins in diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, but there is an increasing body of evidence that is suggesting these tangles are occurring after the fact, that what are really causing the problem are smaller protein assemblies. Figuring out what those assemblies are and how large they are is currently really hard to do, so this may be a way of solving that problem."

INFORMATION:

Gabriel Shemer of Drndi?'s lab and Christopher J. Lanci and Phillip S. Cheng of Saven's lab also contributed to this work.

It was funded by National Science Foundation grant NSEC DMR08-32802 and National Institutes of Health grants R21HG004767 and R01HG006879.

Move over, Katniss Everdeen. For archerfish, the odds are ever in their favor, according to new research from Wake Forest University.

The sharp-shooting fish's ability to spit water to hit food targets has been well documented, but a new study published online in the journal Zoology showed for the first time that there is little difference in the amount of force of their water jets based on target distance. And, when given the choice, the fish preferred closer targets.

The study was co-authored by Wake Forest researchers Morgan Burnette, a biology graduate student, ...

A new study says that global warming has measurably worsened the ongoing California drought. While scientists largely agree that natural weather variations have caused a lack of rain, an emerging consensus says that rising temperatures may be making things worse by driving moisture from plants and soil into the air. The new study is the first to estimate how much worse: as much as a quarter. The findings suggest that within a few decades, continually increasing temperatures and resulting moisture losses will push California into even more persistent aridity. The study appears ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Formula One racing teams may have a lesson to teach business leaders: Innovation can be overrated.

That's the conclusion from academic researchers who pored over data from 49 teams over the course of 30 years of Formula One racing. They found that the teams that innovated the most - especially those that made the most radical changes in their cars - weren't usually the most successful on the race course.

Moreover, radical innovations were the least successful at exactly the times when many business leaders would be most likely to try them: when there ...

A research team at York has adapted the astonishing capacity of animals such as newts to regenerate lost tissues and organs caused when they have a limb severed.

The research, which is funded by a £190,158 award from the medical research charity Arthritis Research UK, is published in Nature Scientific Reports.

The scientists, led by Dr Paul Genever in the Arthritis Research UK Tissue Engineering Centre in the University's Department of Biology, have developed a technique to rejuvenate cells from older people with osteoarthritis to repair worn or damaged cartilage ...

Physicists suggest a new way to look for dark matter: They beleive that dark matter particles annihilate into so-called dark radiation when they collide. If true, then we should be able to detect the signals from this radiation.

The majority of the mass in the Universe remains unknown. Despite knowing very little about this dark matter, its overall abundance is precisely measured. In other words: Physicists know it is out there, but they have not yet detected it.

It is definitely worth looking for, argues Ian Shoemaker, former postdoctoral researcher at Centre ...

Putnam Valley, NY. (Aug. 19, 2015) - A team of researchers in South Korea has successfully transplanted mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) derived from human amniotic membranes of the placenta (AMSCs) into laboratory mice modeled with oxygen-induced retinopathy (a murine model used to mimic eye disease). The treatment aimed at suppressing abnormal angiogenesis (blood vessel growth) which is recognized as the cause of many eye diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. The researchers reported that the AMSCs successfully migrated to the retinas ...

National Institutes of Health (NIH) scientists and colleagues report that an experimental vaccine given six weeks before exposure to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) fully protects rhesus macaques from disease. The vaccine also generated potentially protective MERS-CoV antibodies in blood drawn from vaccinated camels. A study detailing the synthetic DNA vaccine appears in the Aug. 19 Science Translational Medicine. MERS-CoV, which causes pneumonia deep in the lungs, emerged in 2012 and has sickened more than 1,400 people and killed 500, mostly in ...

Summary: In 2011, the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society issued a guideline recommending that neonates undergoing cardiac surgery for repair of congenital heart disease be placed on continuous encephalographic (EEG) monitoring after surgery to detect seizures. These recommendations followed reports that seizures are common in this population, may not be detected clinically, and are associated with adverse neurocognitive outcomes. Yet, in a discussion at the 2014 Annual Meeting of The American Association for Thoracic Surgery, 80% to 90% of the audience was not following ...

KINGSTON - Queen's University researcher Martin Duncan has co-authored a study that solves the mystery of how gas giants such as Jupiter and Saturn formed in the early solar system.

In a paper published this week in the journal Nature, Dr. Duncan, along with co-authors Harold Levison and Katherine Kretke (Southwest Research Institute), explain how the cores of gas giants formed through the accumulation of small, centimetre- to metre-sized, "pebbles.

"As far as we know, this is the first model to reproduce the structure of the outer solar system - two gas giants, two ...

There are fewer smokers in the current generation of adolescents. Current figures show about 25 per cent of teens smoke, down dramatically from 40 per cent in 1987.

But are those who pick up the habit doing so because they have a negative self-image? Does the typical teenaged smoker try to balance out this unhealthy habit with more exercise? And if so, then why would an adolescent smoke, yet still participate in recommended levels of physical activity?

A recent study, conducted in part at Concordia University and published in Preventive Medicine Reports, sought to answer ...