In a paper with four colleagues in the Sept. 2 issue of the journal Nature Communications, Sutherland details how a tiny type of jellyfish - colonial siphonophores - swim rapidly by coordinating multiple water-shooting jets from separate but genetically identical units that make up the animal.

Information on the biomechanics of a living organism that uses such a coordinated system ought to inspire "a natural solution to multi-engine organization that may contribute to the expanding field of underwater-distributed propulsion vehicle design," the co-authors conclude in their paper.

"This is a very interesting system for studying propulsion, because these jellies have multiple swimming bells to use for propulsion," said Sutherland, a biologist with both the UO's Oregon Institute of Marine Biology in Charleston and the Robert D. Clark Honors College on the Eugene campus. "This is relatively rare in the animal kingdom. Most organisms that swim with propulsion do so with a single jet. These siphonophores can turn on a dime, and very rapidly."

The jellies studied are Nanomia bijuga. They are members of the phylum Cnidaria, whose members have specialized stinging cells that are used mainly for capturing prey.

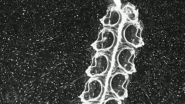

N. bijuga rarely exceed two inches in length but with tentacles can extend to a foot long. Samples were collected -- most often at night when their translucent bodies are easily seen with light over the dark water -- with cups off the floating docks at the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Laboratories. Individual colonies contained from four to 12 jet-like structures known as nectophores.

A single animal, Sutherland said, looks a bit like a bunch of tiny jellyfish strung together. Jellyfish most recognized by ocean lovers are usually much larger and are propelled by a single jet. The tiny versions studied, however, include multiple units and have a clear division of labor.

"The younger swimming bells at the tip of the colony are responsible for turning," Sutherland said. "They generate a lot of torque. The older swimming bells toward the base of the colony are responsible for thrust." Their tentacles capture zooplankton, the tiny organisms that these jellyfish consume, she added.

To understand how these jellies pulse water to maneuver, researchers placed sample colonies in small custom-built tanks and added neutrally buoyant seeding particles as tracers. With the tanks lit with a thin, 2-D laser sheet, the jellies' movement was captured with high-speed digital photography -- at 1,000 frames per second. The data was analyzed with particle image velocimetry, a technique that provides instantaneous velocity measurements.

Most animals and human-engineered vehicles rely on jet thrusters that are turned to change directions, a practice that, Sutherland said, is complicated from a design or engineering standpoint.

"These jellies have a slight ability to turn their individual jets, but they don't need to do it," she said. "With multiple static jets they can achieve all the maneuverability they need. Designing a system like this would be simple yet elegant. And you have redundancies in the system. If one jet goes out, there would be little loss of propulsion."

The research gives insight on how animals can achieve complex levels of maneuverability and performance with relatively simple components, said John "Jack" H. Costello of Providence College in Rhode Island, the study's lead author.

"The nectophores of these jellies appear to be fairly simple jet-producing structures," he said. "When swimming forward, the jets are essentially stereotypic in direction -- they appear to jet in a consistent direction. The complexity of turning is achieved by alternating which units contract and how strongly they jet. Rather than maneuvering by making highly complex physical alterations in jet directions among multiple individuals, the colony has evolved to control relatively simple, stable components using a more complex control system."

The next step, Costello said, it to understand how animals maximize their control of very basic motion patterns to attain such complex results. "We believe the identification of those controlling patterns will permit us to understand the high-performance levels of animal swimmers and that perhaps some of this information will be applicable to human-engineered vehicles.

In her UO lab, Sutherland studies gelatinous organisms, mostly jellyfish, to try to understand how organisms interact with the fluid around them. The fundamental questions that drive her research are how they manipulate the water around them to swim and how they do so to feed.

"My first interaction with the animals used in this research was actually swimming with them in their natural environment," she said. "They are vertical migrators, coming to the surface at night and swimming back into the depths during the day. They can swim hundreds of meters each night."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors were: Sean P. Colin of Rhode Island's Roger Williams University; Brad J. Gemmell of the University of South Florida; and John O. Dabiri of Stanford University. Costello, Colin and Gemmell also are affiliated with the Eugene Bell Center, a marine biology facility in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

This research emerged from a National Science Foundation grant (OCE-1155084) to Sutherland as part of a much larger project involving the authors and others at Friday Harbor Laboratories. The overall project also includes NSF grants to Costello (OCE-1061353), Colin (OCE-1061182) and Dabiri (OCE-1061628).

Sources: Kelly Sutherland, assistant professor of biology, UO Robert D. Clark Honors College and Oregon Institute of Marine Biology, 541-346-8783, ksuth@uoregon.edu; and John Costello, professor of marine biology, Providence College, 401-865-2474, costello@providence.edu

Note: The UO is equipped with an on-campus television studio with a point-of-origin Vyvx connection, which provides broadcast-quality video to networks worldwide via fiber optic network. There also is video access to satellite uplink and audio access to an ISDN codec for broadcast-quality radio interviews.

Links:

Sutherland faculty page: http://oimb.uoregon.edu/?faculty=kelly-sutherland

Sutherland lab: http://pages.uoregon.edu/ksuth/

OIMB: http://oimb.uoregon.edu/

Clark Honors College: https://honors.uoregon.edu/

Costello faculty page: http://www.providence.edu/biology/faculty/Pages/costello.aspx

Eugene Bell Center: http://www.mbl.edu/bell/