(Press-News.org) In use for more than a century, inhaled anesthetics like nitrous oxide and halothane have made modern surgery possible. Now, in experiments in mice, researchers at Johns Hopkins and elsewhere have added to evidence that certain so-called "volatile" anesthetics -- commonly used during surgeries -- may also possess powerful effects on the immune system that can combat viral and bacterial infections in the lung, including influenza and pneumonia.

A report on the experiments is published in the September 1 issue of the journal Anesthesiology.

The Johns Hopkins and University of Buffalo research team built its experiments on previous research showing that children with upper viral respiratory tract infections who were exposed to the anesthetic halothane during minor surgical procedures had significantly less respiratory symptoms and a shorter duration of symptoms compared with children who did not receive halothane during surgeries.

To examine just how some inhaled anesthetic drugs affect viral and bacterial infections, Krishnan Chakravarthy, M.D., Ph.D., a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins Institute of Nanobiotechnology and a resident physician in the department of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Paul Knight, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of anesthesiology at the University of Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, along with others, exposed mice to both influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria.

The team discovered that giving the animals volatile anesthetics, such as halothane, led to decreased bacterial burden and lung injury following infection. The researchers report that the anesthetics augmented the anti-bacterial immune response after influenza viral infection by blocking chemical signaling that involves type I interferon, a group of proteins that help regulate the activity of the immune system.

Using a combination of genetic, molecular, and knockout animal techniques, the researchers found that animals that were exposed to halothane had 450-fold less viable bacteria compared with non-halothane exposed animals with respect to the initial inoculum dose, and astoundingly, treatment made it as if the animals were never infected with a prior influenza virus.

The investigators report that symptoms of piloerection (involuntary bristling of hairs of the skin), hunched posture, impaired gait, labored breathing, lethargy, and weight loss (equal to or greater than 10 percent of body weight at the time of infection) were significantly less in mice exposed to halothane and then infected with flu and S. pneumoniae. Similar results, they say, were seen in mice bred to lack the receptor for type I interferon and not exposed to halothane before infection.

"Our study is giving us more information about how volatile anesthetics work with respect to the immune system," says Chakravarthy. "Given that these drugs are the most common anesthetics used in the operating room," there is a serious need to understand how they work and how we can use their immune effects to our advantage," he adds.

The findings, he says, suggest that volatile anesthetics may someday be helpful for combatting seasonal and pandemic influenza, particularly when there are flu vaccine shortages or limitations. "A therapy based on these inhaled drugs may help deal with new viral and bacterial strains that are resistant to conventional vaccines and treatments and could be a game changer in terms of our preparedness for future pandemics and seasonal flu outbreaks because it's focusing on host immunity," says Chakravarthy. "We hope our study opens the door to the development of new drugs and therapies that could change the infectious disease landscape."

The investigators say they are currently testing an oral small molecule immune modulator in phase 2 clinical trials that acts like volatile anesthetics to help reduce secondary infections after someone becomes sick with the flu.

INFORMATION:

This study was supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL048889), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Extramural Activities (AI084410) and the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (DC013554).

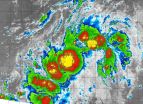

Tropical Depression 14E was born in the Eastern Pacific Ocean early on September 1 when NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP satellite passed overhead and looked at it in infrared light.

Infrared light shows temperature, which is helpful in determining cloud top temperatures of the thunderstorms that make up a tropical cyclone line Tropical Depression 14E (TD 14E). The colder the storm, the higher they stretch into the troposphere (lowest layer of the atmosphere) and the stronger the storms tend to be.

On September 1 at 0900 UTC (5 a.m. EDT), NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP satellite passed ...

Hurricane Ignacio is staying far enough away from the Hawaiian Islands to not bring heavy rainfall or gusty winds, but is still causing rough surf. Infrared satellite data on September 1 shows that wind shear is adversely affecting the storm and weakening it.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite gathers infrared data that reveals temperatures. When NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Ignacio on September 1 at 11:41 UTC (7:41 a.m. EDT), the AIRS data and showed some high, cold, strong thunderstorms surrounded the center ...

EUGENE, Ore. - Sept. 1, 2015 - The University of Oregon's Kelly Sutherland has seen the future of under-sea exploration by studying the swimming prowess of tiny jellyfish gathered from Puget Sound off Washington's San Juan Island.

In a paper with four colleagues in the Sept. 2 issue of the journal Nature Communications, Sutherland details how a tiny type of jellyfish - colonial siphonophores - swim rapidly by coordinating multiple water-shooting jets from separate but genetically identical units that make up the animal.

Information on the biomechanics of a living organism ...

WOODS HOLE, MASS.--Marine animals that swim by jet propulsion, such as squid and jellyfish, are not uncommon. But it's rare to find a colony of animals that coordinates multiple jets for whole-group locomotion. This week in Nature Communications, scientists report on a colonial jellyfish-like species, Nanomia bijuga, that uses a sophisticated, multi-jet propulsion system based on an elegant division of labor among young and old members of the colony. This locomotive solution, the team suggests, could illuminate the design of underwater distributed-propulsion vehicles.

"This ...

Here's another discovery to bolster the case for medical marijuana: New research in mice suggests that THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, may delay the rejection of incompatible organs. Although more research is necessary to determine if there are benefits to humans, this suggests that THC, or a derivative, might prove to be a useful antirejection therapy, particularly in situations where transplanted organs may not be a perfect match. These findings were published in the September 2015 issue of The Journal of Leukocyte Biology.

"We are excited to demonstrate for ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - Forgiveness is a complex process, one often fraught with difficulty and angst. Now, researchers in the University of Missouri College of Human Environmental Sciences studied how different facets of forgiveness affected aging adults' feelings of depression. The researchers found older women who forgave others were less likely to report depressive symptoms regardless of whether they felt unforgiven by others. Older men, however, reported the highest levels of depression when they both forgave others and felt unforgiven by others. The researchers say their ...

Police officers face an elevated risk of being injured in a collision when they are sitting in a stationary car as compared to low-speed driving, as well as when they are responding to an emergency call with their siren blaring as compared to routine patrol, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

In addition, officers face a higher risk of being injured in a crash when they are riding a motorcycle compared to a driving a car, driving solo compared to having a second officer in the car, or not wearing a seatbelt compared to wearing a seatbelt.

The findings provide ...

With a name like "Alcoholic Liver Disease," you may not think about vitamin A as being part of the problem. That's exactly what scientists have shown, however, in a new research report appearing in the September 2015 issue of The FASEB Journal. In particular, they found that chronic alcohol consumption has a dramatic effect on the way the body handles vitamin A. Long-term drinking lowers vitamin A levels in the liver, which is the main site of alcohol breakdown and vitamin A storage, while raising vitamin A levels in many other tissues. This opens the doors for novel treatments ...

The study, published today at Nature Methods (the most prestigious journal for the presentation of results in methods development), proposes the use of two plant protein epitopes, named inntags, as the most innocuous and stable tagging tools in the study of physical and functional interactions of proteins.

Proteins and peptides of various sizes and shapes have been used since the early 80s to tag proteins with many different purposes, ranging from affinity purification to fluorescence-based microscopic detection in whole organisms. However, tagging strategies used nowadays ...

Imagine being in a car with the gas pedal stuck to the floor, heading toward a cliff's edge. Metaphorically speaking, that's what climate change will do to the key group of ocean bacteria known as Trichodesmium, scientists have discovered.

Trichodesmium (called "Tricho" for short by researchers) is one of the few organisms in the ocean that can "fix" atmospheric nitrogen gas, making it available to other organisms. It is crucial because all life -- from algae to whales -- needs nitrogen to grow.

A new study from USC and the Massachusetts-based Woods Hole Oceanographic ...