Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide and ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynaecological cancer. Women who have inherited mutations in genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2 have a very high risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Women at high risk can opt for a double mastectomy to reduce the risk of breast cancer, or removal of their fallopian tubes and ovaries to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer.

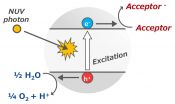

However, the mutations also affect organs that control the menstrual cycle, which has a central role in the development of breast and ovarian cancer. Previous research has shown that specific hormones involved in controlling the menstrual cycle - in particular progesterone - have an effect on the development of cancer. In the breast, progesterone increases the amount of a protein called RANKL, which is one of the triggers for breast cancer.

This means that genetic predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer is a result of the effect the genetic mutations have on hormones that control the menstrual cycle, as well as the effect the mutations have on the cells that develop into tumors.

A new study by researchers at University College London, supported by The Eve Appeal, reveals that women who have a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene have less of a molecule called OPG in their blood. OPG blocks the effects of RANKL, and likely stopping it from triggering breast cancer. RANKL itself is not found at increased levels in the blood in women with a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. However, OPG is unusually low in their blood.

The researchers say that taking a drug that copies the effect of OPG or reduces the effects of progesterone could potentially reduce a woman's risk of breast cancer, but more research is needed to determine whether this is a viable prevention strategy.

"Preventative surgery is quite a drastic measure and we're unsatisfied with the situation - we are aiming to prevent breast cancer, and findings from our research are a significant step forward in demonstrating the importance of why further research is critical in this arena," said lead author Professor Martin Widschwendter. "Women who develop breast cancer as a consequence of their mutation develop cancers associated with poor prognoses that are difficult to treat. Prevention without surgery is the ultimate goal and this study is the first proof of principle - we have identified a new target we can now use to decrease breast cancer risk."

Researchers report on a new mouse model in the second study. Developed by Professor. Louis Dubeau and colleagues at Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, USA, this new model helps researchers understand what's behind the effect of the menstrual cycle on the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

The model uses genetically engineered mice that carry mutations in the equivalent of the human BRCA1 gene, not only in tissues corresponding to those at increased risk of cancer in human BRCA1 mutation carriers, but also in the organs that control the menstrual cycle: the ovaries and the pituitary gland. The model also enables researchers to confine BRCA1 mutations either to tissues at high risk of cancer or to tissues that control the menstrual cycle separately. This gives researchers a tool to understand the effects of the mutations on the menstrual cycle independently from their direct effects on the tissues in which the cancers start.

When developing the mouse model, the researchers observed that some ovarian cancers originate in tissues outside the ovaries and fallopian tubes, suggesting that removal of just the fallopian tubes may not always be an effective prevention strategy in humans.

"We know that the menstrual cycle has an effect on the development of these cancers, but we don't understand the mechanisms behind it," said Prof. Dubeau. "We wanted to develop a mouse model researchers could use to study ways of preventing breast and ovarian cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. We hope this will result in new approaches that will eliminate the need for surgery in the future."

More research is needed into the new prevention strategies. Prof. Widschwendter and the team want to test the effectiveness of OPG in preventing breast cancer, but until they are completely sure it works they cannot conduct a clinical trial to see if OPG prevents cancer development. Instead, in addition to taking advantage of the new mouse model developed in Prof. Dubeau's laboratory, they plan to trial treatment on women at high risk of breast cancer who are waiting for preventative surgery. Instead of waiting for cancer to develop, the trial will monitor biological changes in the tissues at risk of cancer to evaluate the effect of treatment on cancer prevention. The researchers need the support of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 community to take this next step, and will be inviting women to take part in their study.

Athena Lamnisos, Chief Executive of The Eve Appeal said: "This research demonstrates why our focus is on supporting leading edge medical research that seeks to understand how women-specific cancers start. This is a step towards decoding these cancers and understanding how we can develop effective methods of risk prediction and prevention.

"As the UK's only gynaecological cancer research charity, we are championing for more research into prevention, so that we can save significantly more lives and see a future where fewer women develop and more women survive women's cancers," she added.

INFORMATION:

Article details

"Osteoprotegerin (OPG), The Endogenous Inhibitor of Receptor Activator of NF-κB Ligand (RANKL), is Dysregulated in BRCA Mutation Carriers" by Martin Widschwendter, Matthew Burnell, Lindsay Fraser, Adam N. Rosenthal, Sue Philpott, Daniel Reisel, Louis Dubeau, Mark Cline, Yang Pan, Ping-Cheng Yi, D. Gareth Evans, Ian J. Jacobs, Usha Menon, Charles E. Wood, William C. Dougall (doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.08.037).

"A Mouse Model That Reproduces the Developmental Pathways and Site Specificity of the Cancers Associated With the Human BRCA1 Mutation Carrier State" by Ying Liu, Hai-Yun Yen, Theresa Austria, Jonas Pettersson, Janos Peti-Peterdi, Robert Maxson, Martin Widschwendter and Louis Dubeau (doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.08.034).

These articles appear online in EBioMedicine, in press, published by Elsevier. They are available as open access articles on ScienceDirect.

Notes to editors

The Eve Appeal are supporting a range of research programmes into risk prediction and prevention in women who are at risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer; the full programme, BRCA PROTECT, is due to be launched in 2016.

About EBioMedicine

The effective translation of insights gained from biomedical research into improved human health is a global priority. To this end, Elsevier has looked to the leadership of its two leading brands, Cell and The Lancet, to guide the launch of a new comprehensive, online-only open access, rapid publication Elsevier journal, EBioMedicine, focused on forming a community that spans this interface and creates a valuable opportunity for dialogue and collaboration between their respective audiences. As the communities that border this interface are large and diverse, the scope of EBioMedicine covers the entire breadth of translational and clinical research within all disciplines of life and health sciences, ranging from basic science to clinical and public/global health science. The journal is committed to facilitating and incentivizing a robust and successful pipeline for improved human health globally (http://www.ebiomedicine.com).

About The Eve Appeal

The Eve Appeal is the only UK national charity raising awareness and funding research in the five gynaecological cancers - ovarian, womb, cervical, vaginal and vulval. It was set up to save women's lives by funding groundbreaking research focused on developing effective methods of risk prediction, earlier detection and developing screening for these women-only cancers. The charity has grown and developed in parallel with its core research team, the Department of Women's Cancer at University College London (UCL), taking place in 31 institutions across 15 countries. It has played a crucial role in providing seed funding, core infrastructure funding and project funding in addition to campaigning to raise awareness of women-specific cancers. The world-leading research that we fund is ambitious and challenging but our vision is simple: A future where fewer women develop and more women survive gynaecological cancers. http://www.eveappeal.org.uk

About UCL

The Research Department of Women's Cancer, at University College London (UCL), has an exceptionally dedicated group of academics and clinicians to conduct multidisciplinary research into women specific cancers. They strive to create clinical interventions and to extend disease knowledge so that fewer women receive a cancer diagnosis and treatment and quality of life are improved for those who do. In order to achieve this, the Department of Women's Cancer have developed an integrated research pathway including all women specific cancers for risk stratification, prevention, early detection and diagnosis, which incorporates clinical, epidemiological, genetic, epigenetic, proteomic, symptom and imaging data, and applies them to populations.

http://www.instituteforwomenshealth.ucl.ac.uk/womens-cancer

About Elsevier

Elsevier is a world-leading provider of information solutions that enhance the performance of science, health, and technology professionals, empowering them to make better decisions, deliver better care, and sometimes make ground-breaking discoveries that advance the boundaries of knowledge and human progress. Elsevier provides web-based, digital solutions -- among them ScienceDirect, Scopus, Elsevier Research Intelligence and ClinicalKey -- and publishes over 2,500 journals, including The Lancet and Cell, and more than 33,000 book titles, including a number of iconic reference works. Elsevier is part of RELX Group plc, a world-leading provider of information solutions for professional customers across industries.

http://www.elsevier.com

Media contact

Nienke Swankhuisen

Elsevier

+31 204852445

n.swankhuisen@elsevier.com