Research breakthrough in fight against muscle wasting diseases

MUHC research team identifies new drug target considered a potential game-changer for cancer patients

2015-09-15

(Press-News.org) This news release is available in French.

Montreal, September 15th 2015 - It is estimated that half of all cancer patients suffer from a muscle wasting syndrome called cachexia. Cancer cachexia impairs quality of life and response to therapy, which increases morbidity and mortality of cancer patients. Currently, there is no approved treatment for muscle wasting but a new study from the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) and University of Alberta could be a game changer for patients, improving both quality of life and longevity. The research team discovered a new gene involved in muscle wasting that could be a good target for drug development.

The findings, which were published in September's print edition of the FASEB Journal (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology), could have huge clinical implications, as muscle wasting is also associated with other serious illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, heart failure, rheumatoid arthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and is also a prominent feature of aging.

"We discovered that the gene USP19 appears to be involved in human muscle wasting and that in mice, once inhibited, it could protect against muscle wasting, ''says lead author Dr. Simon Wing, MUHC endocrinologist and professor of Medicine at McGill University. "Muscle wasting is a huge unmet clinical need. Recent studies show that muscle wasting is much more common in cancer than we think."

In this study, researchers created mice models that were lacking USP19 (USP19 KO for ''knockout'' mice) and decided to look at two common causes of muscle wasting. They observed whether such mice were resistant to muscle wasting induced by a high level of cortisol - a stress hormone released in your body any time you have a stressful situation such as an illness or a surgery. They also looked at the loss of nerve supply because muscle atrophy can occur following a stroke when people are weak and bedbound. In addition, they looked at USP19 levels in human muscle samples from the most common cancers that cause muscle wasting: lung and gastrointestinal (pancreas, stomach, and colon).

"We found that USP19 KO mice were wasting muscle mass more slowly; in other words, inhibiting USP19 was protecting against both causes of muscle wasting,'' explains Dr. Wing who is also the director of the Experimental Therapeutics and Metabolism Program at the RI-MUHC. "Our results show there was a very good correlation between the expression of this gene in the human muscle samples and other biomarkers that reflect muscle wasting.''

According to recent studies, the prevalence of cachexia is high, ranging from 5 to 15 per cent in chronic heart failure and COPD, and from 60 to 80 per cent in advanced cancer. In all of these chronic conditions, muscle wasting predicts earlier death.

"Cancer patients often present with muscle wasting even prior to their initial cancer diagnosis,'' says Dr. Antonio Vigano, director of the cancer rehabilitation program and cachexia clinic at the MUHC. "In cancer, cachexia also increases your risk of developing toxicity from chemotherapy and other oncological treatments, such as surgery and radiotherapy. At the McGill Nutrition and Performance Laboratory we specialize in cachexia and sarcopenia. By treating these two pathologic conditions through inhibiting the USP19 gene, at an early, rather than late, stage of the cancer trajectory, not only can we potentially improve the quality of life of patients, but also allow them to better tolerate their oncological treatments, to stay at home for a longer period of time, and to prolong their lives.''

INFORMATION:

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Terry Fox Research Institute (TFRI).

The article Inactivation of the ubiquitin-specific protease 19 deubiquitinating enzyme protects against muscle wasting is available online on the FASEB Journal website. The article was co-authored by Nathalie Bédard, Samer Jammoul, Tamara Moore , Marie Plourde, Erin Coyne, and Simon S. Wing, Polypeptide Laboratory and Crabtree Nutrition Laboratories, Department of Medicine, McGill University Health Centre; Stéphanie Chevalier, Crabtree Nutrition Laboratories, Department of Medicine, McGill University Health Centre; Linda Wykes, School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, McGill University, Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, Canada; Patricia L. Hallauer, Kenneth E. M. Hastings, Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Cynthia Stretch and Vickie Baracos, Department of Oncology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

About The Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre

The Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) is a world-renowned biomedical and healthcare research centre. The Institute, which is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine of McGill University, is the research arm of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) - an academic health centre located in Montreal, Canada, that has a mandate to focus on complex care within its community. The RI-MUHC supports over 500 researchers, and over 1,200 students, devoted to a broad spectrum of fundamental, clinical and health outcomes research at the Glen and the Montreal General Hospital sites of the MUHC. Our research facilities offer a dynamic multidisciplinary environment that fosters collaboration and leverages discovery aimed at improving the health of individual patients across their lifespan. Over 1,600 clinical research projects and trials are conducted within the organization annually. The RI-MUHC is supported in part by the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS). http://www.rimuhc.ca

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-09-15

To better inform the tradeoffs involved in land use choices around the world, experts have assessed the value of ecosystem services provided by land resources such as food, poverty reduction, clean water, climate and disease regulation and nutrients cycling.

Their report today estimates the value of ecosystem services worldwide forfeited due to land degradation at a staggering US $6.3 trillion to $10.6 trillion annually, or the equivalent of 10-17% of global GDP.

Furthermore, the problem threatens to force the migration of millions of people from affected areas. ...

2015-09-15

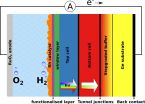

Solar energy is abundantly available globally, but unfortunately not constantly and not everywhere. One especially interesting solution for storing this energy is artificial photosynthesis. This is what every leaf can do, namely converting sunlight to chemical energy. That can take place with artificial systems based on semiconductors as well. These use the electrical power that sunlight creates in individual semiconductor components to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. Hydrogen possesses very high energy density, can be employed in many ways and could replace fossil ...

2015-09-15

Amsterdam, NL, September 9, 2015 - The potential benefits of dietary cocoa extract and/or its final product in the form of chocolate have been extensively investigated in regard to several aspects of human health. Cocoa extracts contain polyphenols, which are micronutrients that have many health benefits, including reducing age-related cognitive dysfunction and promoting healthy brain aging, among others.

Dr. Giulio Maria Pasinetti, MD, PhD, Saunders Family Chair and Professor of Neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Director of Biomedical Training ...

2015-09-15

OAK BROOK, Ill. - Imaging patients soon after traumatic brain injury (TBI) occurs can lead to better (more accurate) detection of cerebral microhemorrhages, or microbleeding on the brain, according to a study of military service members, published online in the journal Radiology.

Cerebral microhemorrhages occur as a direct result of TBI and can lead to severe secondary injuries such as brain swelling or stroke. The ability to monitor the evolution of microhemorrhages could provide important information regarding disease progression or recovery.

According to the Centers ...

2015-09-15

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA (SEPTEMBER 15, 2015). Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS) investigators analyzed updated data on the effects of prenatal myelomeningocele closure on the need for placement of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt within the first 12 months of life. These researchers reaffirm the initial MOMS finding that prenatal repair of a myelomeningocele results in less need for a shunt at 12 months and introduce the new finding that prenatal repair reduces the need for shunt revision in those infants who do require shunt placement. The researchers also found ...

2015-09-15

In what is believed to be the largest, most detailed study of its kind in the United States, scientists at NYU Langone Medical Center and elsewhere have confirmed that tiny chemical particles in the air we breathe are linked to an overall increase in risk of death.

The researchers say this kind of air pollution involves particles so small they are invisible to the human eye (at less than one ten-thousandth of an inch in diameter, or no more than 2.5 micrometers across).

In a report on the findings, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives online Sept. ...

2015-09-15

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, September 15, 2015 -- Prolonged sitting time as well as reduced physical activity contribute to the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in a study of middle-aged Koreans. These findings support the importance of both reducing time spent sitting and increasing physical activity, say researchers. Their results are published in the Journal of Hepatology.

Physical activity is known to reduce the incidence and mortality of various chronic diseases. However, more than one half of the average person's waking day involves sedentary ...

2015-09-15

PHILADELPHIA -- Recent data suggest that epigenetic therapies are likely to provide additional clinical benefit to cancer patients when rationally combined with immunotherapeutic drugs, according to a review published in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"The term epigenetics refers to the study of cellular changes in gene expression that are heritably transmitted during cell replication," said Michele Maio, MD, PhD, chair of medical oncology and immunotherapy, Ospedale Santa Maria alle Scotte, Istituto Toscano Tumori, ...

2015-09-15

Video games are not adequately rated for tobacco content, according to a new UC San Francisco study that found video gamers are being widely exposed to tobacco imagery.

The researchers concluded that a national ratings board set up more than 20 years ago is not a reliable source for learning whether video games contain tobacco imagery.

The study will be published online September 14 in Tobacco Control.

"Parents should stop relying on the ratings to screen for tobacco use in buying video games for their kids," said first author Susan Forsyth, a PhD candidate at ...

2015-09-15

Working shifts of 16 to 24 hours in length is linked to a 60% heightened risk of injury and illness among emergency services (EMS) clinicians, compared to shifts of 8-12 hours, finds research published online in Occupational & Environmental Medicine.

This risk rises in tandem with shift length, the findings show.

The nature of the job requires physical strength to lift and move patients, clear mental focus to deliver medical care in uniquely stressful and often chaotic situations, and sufficient alertness to drive safely, say the researchers.

Yet EMS clinicians often ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Research breakthrough in fight against muscle wasting diseases

MUHC research team identifies new drug target considered a potential game-changer for cancer patients