(Press-News.org) The addition of a daily outdoor activity class at school for three years for children in Guangzhou, China, resulted in a reduction in the rate of myopia (nearsightedness, the ability to see close objects more clearly than distant objects), according to a study in the September 15 issue of JAMA.

Myopia has reached epidemic levels in young adults in some urban areas of East and Southeast Asia. In these areas, 80 percent to 90 percent of high school graduates now have myopia. Myopia also appears to be increasing, more slowly, in populations of European and Middle Eastern origin. Currently, there is no effective intervention for preventing onset. Recent studies have suggested that time spent outdoors may prevent the development of myopia, according to background information in the article.

Mingguang He, M.D., Ph.D., of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, and colleagues conducted a study in which children in grade 1 from 12 primary schools in Guangzhou, China (six intervention schools [n = 952 students]; six control schools [n = 951 students], were assigned to 1 additional 40-minute class of outdoor activities, added to each school day, and parents were encouraged to engage their children in outdoor activities after school hours, especially during weekends and holidays (intervention schools); or children and parents continued their usual pattern of activity (control schools). The average age of the children was 6.6 years.

The 3-year cumulative incidence rate of myopia was 30.4 percent (259 cases among 853 eligible participants) in the intervention group and 39.5 percent (287 cases among 726 eligible participants) in the control group. Cumulative change in spherical equivalent refraction (myopic shift) after 3 years was significantly less in the intervention group than in the control group.

"Our study achieved an absolute difference of 9.1 percent in the incidence rate of myopia, representing a 23 percent relative reduction in incident myopia after 3 years, which was less than the anticipated reduction. However, this is clinically important because small children who develop myopia early are most likely to progress to high myopia, which increases the risk of pathological myopia. Thus a delay in the onset of myopia in young children, who tend to have a higher rate of progression, could provide disproportionate long-term eye health benefits," the authors write.

"Further studies are needed to assess long-term follow-up of these children and the generalizability of these findings."

(doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10803; Available pre-embargo to the media at http:/media.jamanetwork.com)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, financial disclosures, funding and support, etc.

Editorial: Prevention of Myopia in Children

Michael X. Repka, M.D., M.B.A., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, comments on the findings of this study in an accompanying editorial.

"Future studies should include information about the content of the additional outdoor activity, if the activity could be standardized, and how it differs from other studies. This information could guide further study and implementation of outdoor activities in the school setting. Establishing the long-term effect of additional outdoor activities on the development and progression of myopia is particularly important because the intervention is essentially free and may have other health benefits."

"Given the popular appeal of increased outdoor activities to improve the health of school-aged children in general, the potential benefit of slowing myopia development and progression by those same activities is difficult to ignore. Although prescribing this approach with the intent of helping to prevent myopia would appear to have no risk, parents should understand that the magnitude of the effect is likely to be small and the durability is uncertain."

(doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10723; Available pre-embargo to the media at http:/media.jamanetwork.com)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including financial disclosures, funding and support, etc.

INFORMATION:

Women are less likely than men to be full professors at U.S. medical schools, and receive less start-up support from their institutions for biomedical research, according to two studies in the September 15 issue of JAMA.

Women now make up half of all U.S. medical school graduates. However, sex disparities in senior faculty rank persist in academic medicine. Whether differences in age, experience, specialty, and research productivity between sexes explain persistent disparities in faculty rank has not been studied. Anupam B. Jena, M.D., Ph.D., of Harvard Medical School, ...

Patients undergoing surgery for a hip fracture were older and had more medical conditions than patients who underwent an elective total hip replacement, factors that may contribute to the higher risk of in-hospital death and major postoperative complications experienced by hip fracture surgery patients, according to a study in the September 15 issue of JAMA.

Although hip surgery can improve mobility and pain, it can be associated with major postoperative medical complications and mortality. Patients undergoing surgery for a hip fracture are at substantially higher risk ...

Women physicians are substantially less likely to be full professors than men of similar age, experience, specialty and research productivity.

With recent increases in the number of women attending medical school, women now comprise nearly half of all new physicians. But the proportion of women at the rank of fullprofessor at U.S. medical schools has not changed since 1980, despite efforts to increase equity, according to a new research study led by Anupam Jena, associate professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School. The results are published today in JAMA.

"Many ...

A group of scientists from ITMO University, Australian National University and Aalto University called into question the results of a study, published by the researchers from Cambridge University in a prestigious scientific journal Physical Review Letters. In the original study, the British scientists claimed that they managed to find the missing link in the electromagnetic theory. The findings, according to the scientists, could help decrease the size of antennas in electronic devices manifold, promising a major breakthrough in the field of wireless communications.

The ...

Drugs commonly used to treat high blood pressure, and prevent heart attacks and strokes, are associated with significantly worse cardiovascular outcomes in hypertensive African Americans compared to whites, according to a new comparative effectiveness research study led by researchers in the Department of Population Health at NYU Langone Medical Center.

The study, published on September 15 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), is unique, the authors say, in that it evaluates racial differences in cardiovascular outcomes and mortality between hypertensive ...

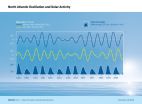

Are climate predictions over periods of several years reliable if weather forecast are still only possible for short periods of several days? Nevertheless there are options to predict the development of key parameters on such long time scales. A new study led by scientists at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel shows how the well-known 11-year cycle of solar activity affects the long-time development of dominant large-scale pressure systems in the Northern Hemisphere.

For their investigations the scientists used a coupled ocean-atmosphere model. In addition, ...

September 15, 2015 - Nyon, Switzerland A study from the University of Southampton and Sheffield Medical School in the UK projects a dramatic increase in the burden of fragility fractures within the next three decades. By 2040, approximately 319 million people will be at high risk of fracture -double the numbers considered at high risk today.

In this first study to estimate the global burden of disease in terms of fracture probability, the researchers quantified the number of individuals worldwide aged 50 years or more at high risk of fracture in 2010 and projected figures ...

Marijuana use among American high school students is significantly lower today than it was 15 years ago, despite the legalization in many states of marijuana for medical purposes, a move toward decriminalization of the drug and the approval of its recreational use in a handful of places, new research suggests.

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers say, however, that marijuana use is significantly greater than the use of other illegal drugs, with 40 percent of teens in 2013 saying they had ever smoked marijuana. That number was down from 47 percent ...

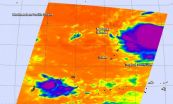

The twentieth tropical depression of the Northwestern Pacific Ocean formed early on September 14 and became a tropical storm the next day, triggering a tropical storm watch. NASA's Aqua satellite passed over the low pressure area as it was consolidating and saw powerful thunderstorms circling the center.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite gathers data in infrared light that provides information about temperatures. The colder the cloud top temperature, the higher the storms are in the troposphere (because the higher ...

TORONTO, Sept. 15, 2015 - A commonly prescribed drug for heart disease may do more good than previously thought. Researchers at York University have found that beta-blockers may prevent further cell death following a heart attack and that could lead to better longer term patient outcomes.

Human hearts are unable to regenerate. When cardiac muscle cells die during and immediately after a heart attack, there is no way to bring the organ back to full health, which contributes to the progression towards eventual heart failure.

Preventing the cells from dying in the first ...