(Press-News.org) To make kefir, it takes a team. A team of microbes.

That's the message of new research from EMBL and Cambridge University's Patil group and collaborators, published in Nature Microbiology today. Members of the group study kefir, one of the world's oldest fermented food products and increasingly considered to be a 'superfood' with many purported health benefits, including improved digestion and lower blood pressure and blood glucose levels. After studying 15 kefir samples, the researchers discovered to their surprise that the dominant species of Lactobacillus bacteria found in kefir grains cannot survive on their own in milk - the other key ingredient in kefir. However, when the species work together, feeding on each other's metabolites in the kefir culture, they each provide something another needs.

"Cooperation allows them to do something they couldn't do alone," says Kiran Patil, group leader and corresponding author of the paper. "It is particularly fascinating how L. kefiranofaciens, which dominates the kefir community, uses kefir grains to bind together all other microbes that it needs to survive - much like the ruling ring of the Lord of the Rings. One grain to bind them all."

A model for microbial interactions

Consumption of kefir originally became popular in Eastern Europe, Israel, and areas in and around Russia. It is composed of 'grains' that look like small pieces of cauliflower and have fermented in milk to produce a probiotic drink composed of bacteria and yeasts.

"People were storing milk in sheepskins and noticed these grains that emerged kept their milk from spoiling, so they could store it longer," says Sonja Blasche, a postdoc in the Patil group and joint first author of the paper. "Because milk spoils fairly easily, finding a way to store it longer was of huge value."

To make kefir, you need kefir grains. These can't be artificially made, but must come from another batch of kefir. The grains are added to milk to ferment and grow. Approximately 24 to 48 hours later (or, in the case of this research, 90 hours later), the kefir grains have consumed the nutrients available to them. The grains grow in size and number in this time and the kefir process is complete. The grains are removed and added to fresh milk to begin the process anew.

For scientists, however, kefir provides more than just a healthy beverage: it's an easy-to-culture model microbial community for studying metabolic interactions. And while kefir is quite similar to yogurt in many ways - both are fermented or cultured dairy products full of 'probiotics' - kefir's microbial community is far larger than yogurt's, including not just bacterial cultures but also yeast.

Learning from kefir

While scientists know that microorganisms often live in communities and depend on their fellow community members for survival, mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited. Laboratory models historically have been limited to two or three microbial species, so Kefir offered - as Kiran describes - a 'Goldilocks zone' of complexity that is not too small (around 40 species), yet not too unwieldy to study in detail.

Sonja started this research by gathering kefir samples from several places. While most samples were obtained in Germany, they're likely to have originated elsewhere, since kefir grains have been passed down over centuries.

"Our first step was to look at how the samples grow. Kefir microbial communities have many member species with individual growth patterns that adapt to their current environment. This means fast- and slow-growing species and some that alter their speed according to nutrient availability," Sonja says. "This is not unique to the kefir community. However, the kefir community had a lot of lead time for co-evolution to bring it to perfection, as they have stuck together for a long time already."

Cooperation is the key

Finding out the extent and the nature of the cooperation between kefir microbes was far from straightforward. To do this, the researchers combined a variety of state-of-the-art methods such as metabolomics (studying metabolites' chemical processes), transcriptomics (studying the genome-produced RNA transcripts), and mathematical modelling. This revealed not only key molecular interaction agents like amino acids, but also the contrasting species dynamics between the grains and the milk part of kefir.

"The kefir grain acts as a base camp for the kefir community, from which community members colonise the milk in a complex yet organised and cooperative manner," Kiran says. "We see this phenomenon in kefir, and then we see it's not limited to kefir. If you look at the whole world of microbiomes, cooperation is also a key to their structure and function."

In fact, in another paper from Kiran's group in collaboration with EMBL's Bork group, out today in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists combined data from thousands of microbial communities across the globe - from soil to the human gut - to understand similar cooperative relationships. In this second paper, the researchers used advanced metabolic modelling to show that the co-occurring groups of bacteria, groups that are frequently found together in different habitats, are either highly competitive or highly cooperative. This stark polarisation hasn't been observed before, and sheds light on evolutionary processes that shape microbial ecosystems. While both competitive and cooperative communities are prevalent, the cooperators seem to be more successful in terms of higher abundance and occupying diverse habitats. Stronger together.

INFORMATION:

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Forest loss declined 18% in African nations where a new satellite-based program provides free alerts when it detects deforestation activities.

A research collaboration that included Jennifer Alix-Garcia of Oregon State University found that the Global Land Analysis and Discovery System, known as GLAD, resulted in carbon sequestration benefits worth hundreds of millions of dollars in GLAD's first two years.

Findings were published today in Nature Climate Change.

The premise of GLAD is simple: Subscribe to the system, launch a free web application, receive email alerts when the GLAD algorithm detects deforestation going on and then take action to save forests.

GLAD, launched in 2016, delivers alerts created ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Cities only occupy about 3% of the Earth's total land surface, but they bear the burden of the human-perceived effects of global climate change, researchers said. Global climate models are set up for big-picture analysis, leaving urban areas poorly represented. In a new study, researchers take a closer look at how climate change affects cities by using data-driven statistical models combined with traditional process-driven physical climate models.

The results of the research led by University of Illinois Urbana Champaign engineer Lei Zhao are published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Home to more than 50% of the world's population, cities experience more heat stress, water scarcity, air pollution ...

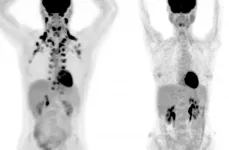

Brown fat is that magical tissue that you would want more of. Unlike white fat, which stores calories, brown fat burns energy and scientists hope it may hold the key to new obesity treatments. But it has long been unclear whether people with ample brown fat truly enjoy better health. For one thing, it has been hard to even identify such individuals since brown fat is hidden deep inside the body.

Now, a new study in Nature Medicine offers strong evidence: among over 52,000 participants, those who had detectable brown fat were less likely than their peers to suffer cardiac and metabolic conditions ranging from type 2 diabetes to coronary artery disease, which ...

Amsterdam, NL, January 4, 2021 - The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with disabilities has not received much attention, perhaps because the disease disproportionately affects older individuals. In this special issue of the Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine experts assess the impact of the pandemic on pediatric patients with special needs, their caregivers, and healthcare providers. They also focus on the growing importance of telemedicine and provide insights and recommendations for mitigating the impact of the virus in the short and long term.

"Pediatric rehabilitation patients frequently ...

TAMPA, Fla. -- Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers among men in the U.S. For many patients, hormone therapy is a treatment option. This type of therapy, also called androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), reduces the level of testosterone and other androgens in the body. Lowering androgen levels can make prostate cancer cells grow more slowly or shrink tumors over time. However, patients receiving ADT often experience higher levels of fatigue, depression and cognitive impairment.

Moffitt Cancer Center researchers are investigating whether inflammation ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Sea ice is a critical indicator of changes in the Earth's climate. A new discovery by Brown University researchers could provide scientists a new way to reconstruct sea ice abundance and distribution information from the ancient past, which could aid in understanding human-induced climate change happening now.

In a study published in Nature Communications, the researchers show that an organic molecule often found in high-latitude ocean sediments, known as tetra-unsaturated alkenone (C37:4), is produced by one or more previously unknown species of ice-dwelling algae. As sea ice concentration ebbs and flows, so do the algae associated with it, as well as the molecules ...

An emerging type of alloy nanoparticle proves more stable, durable than single-element nanoparticles.

Catalysts are integral to countless aspects of modern society. By speeding up important chemical reactions, catalysts support industrial manufacturing and reduce harmful emissions. They also increase efficiency in chemical processes for applications ranging from batteries and transportation to beer and laundry detergent.

As significant as catalysts are, the way they work is often a mystery to scientists. Understanding catalytic processes can help scientists develop more efficient and cost-effective catalysts. In a recent study, scientists from University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) and the U.S. Department of Energy's ...

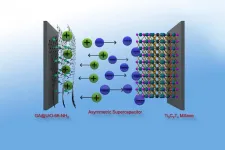

A team working with Roland Fischer, Professor of Inorganic and Metal-Organic Chemistry at the Technical University Munich (TUM) has developed a highly efficient supercapacitor. The basis of the energy storage device is a novel, powerful and also sustainable graphene hybrid material that has comparable performance data to currently utilized batteries.

Usually, energy storage is associated with batteries and accumulators that provide energy for electronic devices. However, in laptops, cameras, cellphones or vehicles, so-called supercapacitors are increasingly installed these days.

Unlike batteries they can quickly store large amounts of energy and put it out just as fast. ...

Forgive Asiatic black bear if they're not impressed with their popular giant panda neighbors.

For decades, conservationists have preached that panda popularity, and the resulting support for their habitat, automatically benefits other animals in the mountainous ranges. That logic extends across the world, as animals regarded as cute, noble or otherwise appealing drum up support to protect where they live.

Yet in Biological Conservation, scientists take a closer look at how other animals under the panda "umbrella" fare and find several species have every reason to be ticked at panda-centric ...

HOUSTON -- Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have discovered that a protein called NF-kappa B-inducing kinase (NIK) is essential for the shift in metabolic activity that occurs with T cell activation, making it a critical factor in regulating the anti-tumor immune response.

The preclinical research, published today in Nature Immunology, suggests that elevating NIK activity in T cells may be a promising strategy to enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy, including adoptive cellular therapies and immune checkpoint blockade.

In a preclinical melanoma model, the researchers evaluated melanoma-specific T cells engineered to express higher levels of NIK. Compared to controls, ...