(Press-News.org) New Columbia Engineering study--first to investigate the long-term effect of soil moisture-atmosphere feedbacks in drylands--finds that soil moisture exerts a negative feedback on surface water availability in drylands, offsetting some of the expected decline

New York, NY--January 4, 2021--Scientists have thought that global warming will increase the availability of surface water--freshwater resources generated by precipitation minus evapotranspiration--in wet regions, and decrease water availability in dry regions. This expectation is based primarily on atmospheric thermodynamic processes. As air temperatures rise, more water evaporates into the air from the ocean and land. Because warmer air can hold more water vapor than dry air, a more humid atmosphere is expected to amplify the existing pattern of water availability, causing the "dry-get-drier, and wet-get-wetter" atmospheric responses to global warming.

A Columbia Engineering team led by Pierre Gentine, Maurice Ewing and J. Lamar Worzel professor of earth and environmental engineering and affiliated with the Earth Institute, wondered why coupled climate model predictions do not project significant "dry-get-drier" responses over drylands, tropical and temperate areas with an aridity index of less than 0.65, even when researchers use the high emissions global warming scenario. Sha Zhou, a postdoctoral fellow at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the Earth Institute who studies land-atmosphere interactions and the global water cycle, thought that soil moisture-atmosphere feedbacks might play an important part in future predictions of water availability in drylands.

The new study, published today by Nature Climate Change, is the first to show the importance of long-term soil moisture changes and associated soil moisture-atmosphere feedbacks in these predictions. The researchers identified a long-term soil moisture regulation of atmospheric circulation and moisture transport that largely ameliorates the potential decline of future water availability in drylands, beyond that expected in the absence of soil moisture feedbacks.

"These feedbacks play a more significant role than realized in long-term surface water changes," says Zhou. "As soil moisture variations negatively impact water availability, this negative feedback could also partially reduce warming-driven increases in the magnitudes and frequencies of extreme high and extreme low hydroclimatic events, such as droughts and floods. Without the negative feedback, we may experience more frequent and more extreme droughts and floods."

The team combined a unique, idealized multi-model land-atmosphere coupling experiment with a novel statistical approach they developed for the study. They then applied the algorithm on observations to examine the critical role of soil moisture-atmosphere feedbacks in future water availability changes over drylands, and to investigate the thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms underpinning future water availability changes due to these feedbacks.

They found, in response to global warming, strong declines in surface water availability (precipitation minus evaporation, P-E) in dry regions over oceans, but only slight P-E declines over drylands. Zhou suspected that this phenomenon is associated with land-atmosphere processes. "Over drylands, soil moisture is projected to decline substantially under climate change," she explains. "Changes in soil moisture would further impact atmospheric processes and the water cycle."

Global warming is expected to reduce water availability and hence soil moisture in drylands. But this new study found that the drying of soil moisture actually negatively feeds back onto water availability--declining soil moisture reduces evapotranspiration and evaporative cooling, and enhances surface warming in drylands relative to wet regions and the ocean. The land-ocean warming contrast strengthens the air pressure differences between ocean and land, driving greater wind blowing and water vapor transport from the ocean to land.

"Our work finds that soil moisture predictions and associated atmosphere feedbacks are highly variable and model dependent," says Gentine. "This study underscores the urgent need to improve future soil moisture predictions and accurately represent soil moisture-atmosphere feedbacks in models, which are critical to providing reliable predictions of dryland water availability for better water resources management."

INFORMATION:

About the Study

The study is titled "Soil moisture-atmosphere feedbacks mitigate declining water availability in dryland."

Authors are: Sha Zhou 1,2,3,4,5; A. Park Williams 1; Benjamin R. Lintner 6; Alexis M. Berg 7; Yao Zhang 4,5; Trevor F. Keenan 4,5; Benjamin I. Cook 1,8; Stefan Hagemann 9; Sonia I. Seneviratne 10; Pierre Gentine 2,3

1 Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University

2 Earth Institute, Columbia University

3 Department of Earth and Environmental Engineering Columbia University

4 Climate and Ecosystem Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

5 Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management UC

6 Department of Environmental Sciences Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

7 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University

8 NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies

9 Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht Institute of Coastal Research, Germany

10 Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science ETH Zurich

The study was supported by NASA ROSES Terrestrial hydrology (NNH17ZDA00IN-THP) and NOAA MAPP NA17OAR4310127, Lamont-Doherty Postdoctoral Fellowship, and the Earth Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship.

The authors declare no competing interests.

LINKS:

Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-020-00945-z

DOI: 10.1038/s41558-020-00945-z

http://engineering.columbia.edu/

https://engineering.columbia.edu/faculty/pierre-gentine

https://eee.columbia.edu/

http://ei.columbia.edu/

Columbia Engineering

Columbia Engineering, based in New York City, is one of the top engineering schools in the U.S. and one of the oldest in the nation. Also known as The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, the School expands knowledge and advances technology through the pioneering research of its more than 220 faculty, while educating undergraduate and graduate students in a collaborative environment to become leaders informed by a firm foundation in engineering. The School's faculty are at the center of the University's cross-disciplinary research, contributing to the Data Science Institute, Earth Institute, Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, Precision Medicine Initiative, and the Columbia Nano Initiative. Guided by its strategic vision, "Columbia Engineering for Humanity," the School aims to translate ideas into innovations that foster a sustainable, healthy, secure, connected, and creative humanity.

ANN ARBOR, Michigan -- Michael Green, M.D., Ph.D., noticed that when his patients had cancer that spread to the liver, they fared poorly - more so than when cancer spread to other parts of the body. Not only that, but transformative immunotherapy treatments had little impact for these patient.

Uncovering the reason and a possible solution, a new study, published in Nature Medicine, finds that tumors in the liver siphon off critical immune cells, rendering immunotherapy ineffective. But coupling immunotherapy with radiotherapy to the liver in mice restored the immune cell function and led to better outcomes.

"Patients with liver metastases receive little benefit from immunotherapy, a treatment that has been a game-changer for many cancers. Our research suggests ...

MADISON, Wis. -- Deforestation dropped by 18 percent in two years in African countries where organizations subscribed to receive warnings from a new service using satellites to detect decreases in forest cover in the tropics.

The carbon emissions avoided by reducing deforestation were worth between $149 million and $696 million, based on the ability of lower emissions to reduce the detrimental economic consequences of climate change.

Those findings come from new research into the effect of GLAD, the Global Land Analysis and Discovery system, available on the free and interactive ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Scientists have developed a machine-learning method that crunches massive amounts of data to help determine which existing medications could improve outcomes in diseases for which they are not prescribed.

The intent of this work is to speed up drug repurposing, which is not a new concept - think Botox injections, first approved to treat crossed eyes and now a migraine treatment and top cosmetic strategy to reduce the appearance of wrinkles.

But getting to those new uses typically involves a mix of serendipity and time-consuming and expensive randomized clinical trials to ensure that a drug deemed effective for one disorder will be useful as a treatment for something else.

The Ohio State University researchers ...

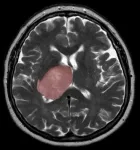

The healing process that follows a brain injury could spur tumour growth when new cells generated to replace those lost to the injury are derailed by mutations, Toronto scientists have found. A brain injury can be anything from trauma to infection or stroke.

The findings were made by an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Toronto, The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre who are also on the pan-Canadian Stand Up To Cancer Canada Dream Team that focuses on a common brain cancer known as glioblastoma.

"Our data suggest that the right mutational change in particular cells in the brain could be modified by injury to give rise to a tumour," says Dr. Peter Dirks, Dream ...

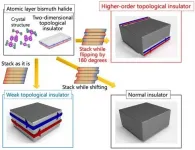

Spintronics refers to a suite of physical systems which may one day replace many electronic systems. To realize this generational leap, material components that confine electrons in one dimension are highly sought after. For the first time, researchers created such a material in the form of a special bismuth-based crystal known as a high-order topological insulator.

To create spintronic devices, new materials need to be designed that take advantage of quantum behaviors not seen in everyday life. You are probably familiar with conductors and insulators, which permit and restrict the flow of electrons, respectively. ...

Some racial and ethnic groups suffer relatively more often, and fare worse, from common ailments compared to others. Prostate cancer is one disease where such health disparities occur: risk for the disease is about 75 percent higher, and prostate cancer is more than twice as deadly, in Blacks compared to whites. Yet whites are often overrepresented as research participants, making these differences difficult to understand and, ultimately, address.

With this problem in mind, scientists at the USC Center for Genetic Epidemiology and the Institute for Cancer Research, London, ...

Last year, more than fifty years after initial theoretical proposals, researchers in Pisa, Stuttgart and Innsbruck independently succeeded for the first time in creating so-called supersolids using ultracold quantum gases of highly magnetic lanthanide atoms. This state of matter is, in a sense, solid and liquid at the same time. "Due to quantum effects, a very cold gas of atoms can spontaneously develop both a crystalline order of a solid crystal and particle flow like a superfluid quantum liquid, i.e. a fluid able to flow without any friction" explains Francesca Ferlaino from the Institute for Quantum Optics and Quantum Information of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Department of Experimental Physics at the ...

Research from the University of Kent's Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE) has found that elephant ivory is still being sold on the online marketplace eBay, despite its 10-year-old policy banning the trade in ivory.

The trafficking of wildlife over the internet continues to be a problem, with the detection of illegal activity being challenging. Despite efforts of law enforcement, the demand for illegal wildlife products online has continued to increase. In some cases vendors have adopted the use of 'code words' to disguise the sale of illicit items.

Sofia Venturini ...

PORTLAND, Ore. - Researchers at Oregon State University have found that a few organisms in the gut microbiome play a key role in type 2 diabetes, opening the door to possible probiotic treatments for a serious metabolic disease affecting roughly one in 10 Americans.

"Type 2 diabetes is in fact a global pandemic and the number of diagnoses is expected to keep rising over the next decade," said study co-leader Andrey Morgun, associate professor of pharmaceutical sciences in the OSU College of Pharmacy. "The so-called 'western diet' - high in saturated fats and refined sugars - is one of the primary factors. But gut bacteria have an important role to play in modulating the effects of diet."

Formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, type 2 diabetes is a chronic condition ...

To make kefir, it takes a team. A team of microbes.

That's the message of new research from EMBL and Cambridge University's Patil group and collaborators, published in Nature Microbiology today. Members of the group study kefir, one of the world's oldest fermented food products and increasingly considered to be a 'superfood' with many purported health benefits, including improved digestion and lower blood pressure and blood glucose levels. After studying 15 kefir samples, the researchers discovered to their surprise that the dominant species of Lactobacillus ...