Now, working with mice, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine and the University of Lausanne in Switzerland have identified that missing link -- an immune system cell that they say travels from the gut to the brain and attacks cells rather than protect them as it normally does.

The team's findings are published Jan. 6, 2021, in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Seen in as many as 12% of infants weighing less than 3.5 pounds at birth, NEC is a rapidly progressing gastrointestinal emergency in which bacteria invade the wall of the colon and cause inflammation that can ultimately destroy healthy tissue at the site. If enough cells become necrotic (die) so that a hole is created in the intestinal wall, bacteria can enter the bloodstream and cause life-threatening sepsis.

In a 2018 mouse study, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center found that animals with NEC make a protein called toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) that binds to bacteria in the gut and precipitates the intestinal destruction. They also determined that TLR4 simultaneously activates immune cells in the brain known as microglia, leading to white matter loss, brain injury and diminished cognitive function. What wasn't clear was how the two are connected.

For this latest study, the researchers speculated that CD4+ T lymphocytes -- immune system cells also known as helper T cells -- might be the link. CD4+ T cells get their "helper" nickname because they help another type of immune cell called a B lymphocyte (or B cell) respond to surface proteins -- antigens -- on cells infected by foreign invaders such as bacteria or viruses. Activated by the CD4+ T cells, immature B cells become either plasma cells that produce antibodies to mark the infected cells for disposal from the body or memory cells that "remember" the antigen's biochemistry for a faster response to future invasions.

CD4+ T cells also send out chemical messengers that bring another type of T cell -- known as a killer T cell -- to the area so that the targeted infected cells can be removed. However, if this activity occurs in the wrong place or at the wrong time, the signals may inadvertently direct the killer T cells to attack healthy cells instead.

"We knew from comparing the brains of infants with NEC with ones from infants who died from other causes that the former had accumulations of CD4+ T cells and showed increased microglial activity," says study senior author David Hackam, M.D., Ph.D., surgeon-in-chief at Johns Hopkins Children's Center and professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "We suspected that these T cells came from the NEC-inflamed regions of the gut and set out to prove it by using neonatal mice as a model of what happens in human infants."

In the first of a series of experiments, the researchers induced NEC in infant mice and then examined their brains. As expected, the tissues showed a significant increase in CD4+ T cells as well as higher levels of a protein associated with increased microglial activity. In a follow up test, the researchers showed that mice with NEC had a weakened blood-brain barrier -- the biological wall that normally prevents bacteria, viruses and other hazardous materials circulating in the bloodstream from reaching the central nervous system. This could, the researchers surmised, explain how CD4+ T cells from the gut could travel to the brain.

Next, the researchers determined that accumulating CD4+ T cells were the cause of the brain injury seen with NEC. They did this first by biologically blocking the movement of the helper T cells into the brain and then in a separate experiment, neutralizing the T cells by binding them to a specially designed antibody. In both cases, microglial activity was subdued and white matter in the brain was preserved.

To further define the role of CD4+ T cells in brain injury, the researchers harvested T cells from the brains of mice with NEC and injected them into the brains of mice bred to lack both T and B lymphocytes. Compared with control mice that did not receive any T cells, the mice that did receive the lymphocytes had higher levels of the chemical signals which attract killer T cells. The researchers also observed activation of the microglia, inflammation of the brain and loss of white matter -- all markers of brain injury.

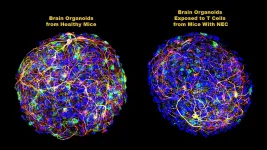

The researchers then sought to better define how the accumulating CD4+ T cells were destroying white matter -- actually a fat called myelin that covers and protects neurons in the brain, and facilitates communication between them. To do this, they used organoids, mouse brain cells grown in the laboratory to simulate the entire brain. Brain-derived CD4+ T cells from mice with NEC were added to these laboratory "mini-brains" and then examined for several weeks.

Hackam and his colleagues found that a specific chemical signal from the T cells -- a cytokine (inflammatory protein) known as interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) -- increased in the organoids as the amount of myelin decreased. This activity was not seen in the organoids that received CD4+ T cells from mice without NEC.

After adding IFN-gamma alone to the organoids, the researchers saw the same increased levels of inflammation and reduction of myelin that they had seen in mice with NEC. When they added an IFN-gamma neutralizing antibody, cytokine production was significantly reduced, inflammation was curtailed and white matter was partially restored.

The researchers concluded that IFN-gamma directs the process leading to NEC-related brain injury. Their finding was confirmed when an examination of brain tissues from mice with NEC revealed higher levels of IFN-gamma than in tissues from mice without the disease.

Next, the researchers investigated whether CD4+ T cells could migrate from the gut to the brain of mice with NEC. To do this, they obtained CD4+ T cells from the intestines of infant mice with and without NEC. Both types of cells were injected into the brains of infant mice in two groups -- one set that could produce the protein Rag1 and one that could not. Rag1-deficient mice do not have mature T or B lymphocytes.

The Rag1-deficient mice that received gut-derived helper T cells from mice with NEC showed the same characteristics of brain injury seen in the previous experiments. T cells from both mice with and without NEC did not cause brain injury in mice with Rag1, nor did T cells from mice without NEC in Rag1-deficient mice. This showed that the gut-derived helper T cells from mice with NEC were the only ones that could cause brain injury.

In a second test, gut-derived T cells from mice with and without NEC were injected into the peritoneum -- the membrane lining the abdominal cavity -- of Rag1-deficient mice. Only the intestinal T cells from mice with NEC led to brain injury.

This finding was confirmed by genetically sequencing the same portions from both the brain-derived and gut-derived T lymphocytes from mice with and without NEC. The sequences of the helper T cells from mice with NEC, on average, were 25% genetically similar while the ones from mice without NEC were only 2% alike.

In a final experiment, the researchers blocked IFN-gamma alone. Doing so provided significant protection against the development of brain injury in mice with severe NEC. This suggests, the researchers say, a therapeutic approach that could benefit premature infants with the condition.

"Our research strongly suggests that helper T cells from intestines inflamed by NEC can migrate to the brain and cause damage," says Hackam. "The mouse model in our study was previously shown to closely match what occurs in humans, so we believe that this is the likely mechanism by which NEC-related brain injury develops in premature infants."

Based on these findings, Hackam says measures for preventing this type of brain injury, including therapies to block the action of INF-gamma, may be possible.

INFORMATION:

Along with Hackam, the Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers on the study team are Qinjie Zhou, Diego Niño, Yukihiro Yamaguchi, Sanxia Wang, William Fulton, Hongpeng Jia, Peng Lu, Thomas Prindle, Meaghan Morris, Chhinder Sodhi and Liam Chen (now at the University of Minnesota). Also on the team is David Pamies from the University of Lausanne.

The study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants RO1DK117186, RO1DK121824, RO1GM078238, RO1AI148446 and R21AI49321.

Hackam, Sodhi and Pamies have patents on NEC treatments that are unrelated to the research in this study. The other authors declare no competing interests.