(Press-News.org) Step into your new, microscopic time machine. Scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder have discovered that a type of single-celled organism living in modern-day oceans may have a lot in common with life forms that existed billions of years ago--and that fundamentally transformed the planet.

The new research, which will appear Jan. 6 in the journal Science Advances, is the latest to probe the lives of what may be nature's hardest working microbes: cyanobacteria.

These single-celled, photosynthetic organisms, also known as "blue-green algae," can be found in almost any large body of water today. But more than 2 billion years ago, they took on an extra important role in the history of life on Earth: During a period known as the "Great Oxygenation Event," ancient cyanobacteria produced a sudden, and dramatic, surge in oxygen gas.

"We see this total shift in the chemistry of the oceans and the atmosphere, which changed the evolution of life, as well," said study lead author Sarah Hurley, a postdoctoral research associate in the departments of Geological Sciences and Biochemistry. "Today, all higher animals need oxygen to survive."

To date, scientists still don't know what these foundational microbes might have looked like, where they lived or what triggered their transformation of the globe.

But Hurley and her colleagues think they might have gotten closer to an answer by drawing on studies of naturally-occurring and genetically-engineered cyanobacteria. The team reports that these ancient microbes may have floated freely in an open ocean and resembled a modern form of life called beta-cyanobacteria.

Studying them, the researchers said, offers a window into a time when single-celled organisms ruled the Earth.

"This research gave us the unique opportunity to form and test hypotheses of what the ancient Earth might have looked like, and what these ancient organisms could have been," said co-author Jeffrey Cameron, an assistant professor of biochemistry.

Take a breath

You can still make the case that cyanobacteria rule the planet. Hurley noted that these organisms currently produce about a quarter of the oxygen that comes from the world's oceans.

One secret to their success may lie in carboxysomes--or tiny, protein-lined compartments that float inside all living cyanobacteria. These pockets are critical to the lives of these organisms, allowing them to concentrate molecules of carbon dioxide within their cells.

"Being able to concentrate carbon allows cyanobacteria to live at what are, in the context of Earth's history, really low carbon dioxide concentrations," Hurley said.

Before the Great Oxidation Event, it was a different story. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere may have been as much as 100 times what they are today, and oxygen was almost nonexistent. For that reason, many scientists long assumed that ancient microorganisms didn't need carboxysomes for concentrating carbon dioxide.

"Cyanobacteria have persisted in some form over two billion years of Earth's history," she said. "They could have been really different than today's cyanobacteria."

To find out how similar they were, the researchers cultured jars filled with bright-green cyanobacteria under conditions resembling those on Earth 2 billion years ago.

Hurley explained that different types of cyanobacteria prefer to digest different forms, or "isotopes," of carbon atoms. As a result, when they grow, die and decompose, the organisms leave behind varying chemical signatures in ancient sedimentary rocks.

"We think that cyanobacteria were around billions of years ago," she said. "Now, we can get at what they were doing and where they were living at that time because we have a record of their metabolism."

Resurrecting zombie microbes

In particular, the team studied two different types of cyanobacteria. They included beta-cyanobacteria, which are common in the oceans today. But the researchers also added a new twist to the study. They attempted to bring an ancient cyanobacterium back from the dead. Hurley and her colleagues used genetic engineering to design a special type of microorganism that didn't have any carboxysomes. Think of it like a zombie cyanobacterium.

"We had the ability to do what was essentially a physiological resurrection in the lab," said Boswell Wing, a study coauthor and associate professor of geological sciences.

But when the researchers studied the metabolism of their cultures, they found something surprising: Their zombie cyanobacterium didn't seem to produce a chemical signature that aligned with the carbon isotope signatures that scientists had previously seen in the rock record. In fact, the best fit for those ancient signals were likely beta-cyanobacteria--still very much alive today.

The team, in other words, appears to have stumbled on a living fossil that was hiding in plain sight. And, they said, it's clear that cyanobacteria living around the time of the Great Oxygenation Event did have a structure akin to a carboxysome. This structure may have helped cells to protect themselves from growing concentrations of oxygen in the air.

"That modern organisms could resemble these ancient cyanobacteria--that was really counterintuitive," Wing said.

Scientists, they note, now have a much better idea of what ancient cyanobacteria looked like and where they lived. And that means that they can begin running experiments to dig deeper into what life was like in the 2 billion-year-old ocean.

"Here is hard evidence from the geological record and a model organism that can shed new light on life on ancient Earth," Cameron said.

INFORMATION:

Other coauthors on the new paper included CU Boulder undergraduate student Claire Jasper and graduate student Nicholas Hill.

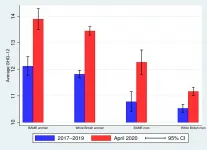

In the UK, men from ethnic minorities and women may have experienced worse mental health declines than White British men, according to a study published January 6, 2021 in the open access journal PLOS ONE by Eugenio Proto and Climent Quintana-Domeque of institutions including the University of Glasgow and the University of Exeter, UK.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the measures enacted to restrict the spread of the virus, have had a major impact on the lives of citizens globally. The authors of the present study examined changes in mental health associated with the pandemic across ethnic groups in the UK.

The researchers used data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, comparing responses from participants between 2017 and 2019 (i.e.: prior to the pandemic) to responses from ...

CAR T cells are a breakthrough class of effective but often toxic cancer therapies

To prevent overactivation, switchable CAR T cells were engineered that can be turned on and off with an approved, widely used cancer drug

BOSTON - Scientists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Mass General Cancer Center have created molecular ON-OFF switches to regulate the activity of CAR T cells, a potent form of cell-based immunotherapy that has had dramatic success in treating some advanced cancers, but which pose a significant risk of toxic side effects.

CAR T cells are immune cells genetically modified to recognize and attack tumors ...

The distribution and concentration of dissolved oxygen and water temperature in the oceans and freshwaters are usually far more influential in shaping the growth and reproduction of fish than the distribution of their prey.

In a new paper in Science Advances, Daniel Pauly, principal investigator of the Sea Around Us initiative at UBC's Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, argues that scientists need to avoid attaching human attributes to fish and start looking at their unique biology and constraints through a different lens.

This lens is Pauly's own Gill Oxygen Limitation Theory (GOLT), ...

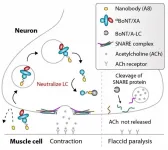

New York City, January 6, 2021 - CytoDel, Inc. ("CytoDel" or "the Company"), a privately-held corporation, today announces the publication of preclinical data on the Company's lead product, Cyto-111, in the peer-reviewed journal, Science Translational Medicine. The complete text of the article titled, "Neuronal Delivery of Antibodies has Therapeutic Effects in Animal Models of Botulism," can be found here.

Cyto-111 was conceived, expressed and purified in the laboratory of Konstantin Ichtchenko, Ph.D., NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, who was a principal investigator in the study, which ...

A large scale study from Bentley University of the biotechnology companies that completed Initial Public Offerings from 1997-2016 estimates that 78% of these companies are associated with products that reach phase 3 trials and 52% are associated with new product approvals. The article, titled "Late-stage product development and approvals by biotechnology companies after IPO, 1997-2016," shows that these emerging, public biotechnology companies continue to have a role in initiating new product development, but are no longer distinctively focused on novel, biological products.

The new report from the Center for Integration of Science and Industry at Bentley University, published in Clinical Therapeutics, studied the 319 biotechnology ...

E. coli food poisoning is one of the worst food poisonings, causing bloody diarrhea and kidney damage. But all the carnage might be just an unintended side effect, researchers from UConn Health report in the 27 November issue of Science Immunology. Their findings might lead to more effective treatments for this potentially deadly disease.

Escherichia coli are a diverse group of bacteria that often live in animal guts. Many types of E. coli never make us sick; other varieties can cause traveler's diarrhea. But swallowing even a few cells of the type of E. coli that makes Shiga toxin can make us very, very ill. Shiga toxin damages blood vessels in the intestines, causing bloody diarrhea. If ...

Taking advantage of the chemical properties of botulism toxins, two teams of researchers have fashioned non-toxic versions of these compounds that can deliver therapeutic antibodies to treat botulism, a potentially fatal disease with few approved treatments. The research, which was conducted in mice, guinea pigs, and nonhuman primates, suggests that the toxin derivatives could one day offer a platform to quickly treat established cases of botulism and target hard-to-reach molecules within neurons. Botulism manifests due to bacterial toxins called botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), which are the most potent toxins known ...

The pandemic has exacerbated isolation and fears for one very vulnerable group of Americans: the 4.3 million older adults with cognitive impairment who live alone.

As the coronavirus continues to claim more lives and upend others, researchers led by UC San Francisco are calling for tailored services and support for older adults living alone with memory issues, who are experiencing extreme isolation, and are exposed to misinformation about the virus and barriers to accessing medical care.

In their qualitative study, researchers interviewed 24 San Francisco Bay Area residents whose average age was 82. Of these, 17 were women, and 13 were either monolingual Spanish-speakers ...

LA JOLLA--New data suggest that nearly all COVID-19 survivors have the immune cells necessary to fight re-infection.

The findings, based on analyses of blood samples from 188 COVID-19 patients, suggest that responses to the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, from all major players in the "adaptive" immune system, which learns to fight specific pathogens, can last for at least eight months after the onset of symptoms from the initial infection.

"Our data suggest that the immune response is there--and it stays," LJI Professor Alessandro Sette, Dr. Biol. Sci., who co-led the study with LJI Professor Shane Crotty, ...

Drug-resistant bacteria could lead to more deaths than cancer by 2050, according to a report commissioned by the United Kingdom in 2014 and jointly supported by the U.K. government and the Wellcome Trust. In an effort to reduce the potential infection-caused 10 million deaths worldwide, Penn State researcher Scott Medina has developed a peptide, or small protein, that can target a specific pathogen without damaging the good bacteria that bolsters the immune system.

Medina, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering, led the team who published its results Jan. 4 in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

"One of the best protective mechanisms we have to prevent infection are beneficial bacteria that inhabit our bodies, known as commensals," ...