BOSTON - Scientists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Mass General Cancer Center have created molecular ON-OFF switches to regulate the activity of CAR T cells, a potent form of cell-based immunotherapy that has had dramatic success in treating some advanced cancers, but which pose a significant risk of toxic side effects.

CAR T cells are immune cells genetically modified to recognize and attack tumors cells. Once given, these "living drugs" proliferate and kill tumor cells over weeks to months, in some cases causing life-threatening inflammatory reactions that are difficult to control. In this way, CAR T cells are unlike more established forms of cancer therapy - chemotherapy or radiotherapy for instance - whose dose can be precisely tuned up or down over time.

The scientists reported in Science Translational Medicine the development of switchable CAR T cells that can be turned on or off by giving a commonly used cancer drug, lenalidomide. In the laboratory, the researchers designed OFF-switch CAR T cells that could be quickly, reversibly turned off by administering the drug, after which the CAR T cells recovered their anti-tumor activity. Separately, the researchers also reported ON-switch CAR T cells that only killed tumor cells during lenalidomide treatment.

In the future, switchable cell therapies might allow patients with their physicians to take a pill - or not - to tune the amount of CAR T cell activity from day to day, hopefully reducing toxic side effects.

"From the start, our goal was to build cancer therapies that are less hard on people. Having built these switches using human genetic sequences and an FDA-approved drug, we are excited for the potential to translate this research to clinical use," said Max Jan, MD, PhD, first author of the report. He is affiliated with the laboratories of Benjamin Ebert, MD, PhD, and Marcela Maus, MD, PhD, the report's senior authors. Other authors include researchers from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and Harvard Medical School.

CAR T cells are created by harvesting immune T cells from the patient and reprogramming them in the laboratory to produce a finely-tuned receptor molecule, termed a CAR (for chimeric antigen receptor), that recognizes a distinctive protein on the surface of the patient's cancer cells. The CAR T cells, after being engineered in the lab and returned to the patient, circulate through the body and home in on the cancer cells by binding to the distinctive surface protein they have been engineered to recognize. This binding event stimulates an immune attack, destruction of the cancer cells, and proliferation of the CAR T cells.

A drawback, however, is that uncontrolled proliferation of the CAR T cells sometimes triggers cytokine release syndrome (CRS), the release of inflammation-causing signals throughout the body that can cause toxicities ranging from mild fever to life-threatening organ failure. Current management of these toxic reactions relies on intensive care unit support and drugs including immunosuppressive corticosteroids, while many researchers are trying to develop methods of controlling the activity of CAR T cells in order to prevent these toxic side effects.

"CAR T cells can be fantastically effective therapies, but they can also have serious toxicities and can cause significant morbidity and mortality," said Ebert who is Chair of Medical Oncology at Dana-Farber. "They are currently difficult to control once administered to the patient."

CAR T cell therapy has had most success in blood cancers. Three CAR T agents have been approved: Kymriah for children and young adults with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), both Kymriah and Yescarta for treatment of adults with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Tecartus for adults with mantle cell lymphoma. Scientists are investigating an array of different approaches with the aim of extending the reach of CAR T therapies to other blood cancers and to solid tumors, if a number of hurdles can be overcome, including the problem of treatment toxicity.

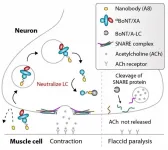

To create the ON and OFF switch systems for CAR T cells, the scientists used a relatively new technique known as targeted protein degradation. It exploits a mechanism that cells use to dispose of unwanted or abnormal proteins; the proteins are marked for destruction by a structure within cells that acts like a garbage disposal. A small number of drugs, including lenalidomide, act by targeting specific proteins for degradation using this pathway.

The researchers used this technique to engineer small protein tags that are sent to the cellular garbage disposal by lenalidomide. When this degradation tag was affixed to the CAR, it allowed the tagged CAR to be degraded during drug treatment, thereby stopping T cells from recognizing cancer cells. Because CAR proteins are continually manufactured by these engineered T cells, after drug treatment new CAR proteins accumulate and restore the cell's anti-tumor function. The researchers propose that the switch system might in the future allow patients to have their CAR T cell treatment temporarily paused to prevent short-term toxicity and still have long-term therapeutic effects against their cancer.

The scientists also built an ON-switch CAR by further engineering the proteins that physically interact with lenalidomide. This system has the potential to be especially safe, because the T cells only recognize and attack tumor cells during drug treatment. If used to treat cancers such as multiple myeloma that are sensitive to lenalidomide, ON-switch CAR T cells could allow for a coordinated attack by the immune cells and the drug that controls them.

"The long-term goal is to have multiple different drugs that control different on and off switches" so that scientists can develop "ever-more complex cellular therapies," explained Ebert.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants (R01HL082945, P01CA108631, and P50CA206963), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Edward P. Evans

Foundation, and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

About Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute is one of the world's leading centers of cancer research and treatment. Dana-Farber's mission is to reduce the burden of cancer through scientific inquiry, clinical care, education, community engagement, and advocacy. We provide the latest treatments in cancer for adults through Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center and for children through Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. Dana-Farber is the only hospital nationwide with a top 10 U.S. News & World Report Best Cancer Hospital ranking in both adult and pediatric care.

As a global leader in oncology, Dana-Farber is dedicated to a unique and equal balance between cancer research and care, translating the results of discovery into new treatments for patients locally and around the world, offering more than 1,100 clinical trials.