"Our goal is to make a single-shot vaccine that does not require a cold-chain for storage or transport. If we're successful at doing it well, it should be cheap too," said Kim, who is the Virginia and D. K. Ludwig Professor of Biochemistry. "The target population for our vaccine is low- and middle-income countries."

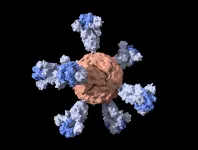

Their vaccine, detailed in a paper published Jan. 5 in ACS Central Science, contains nanoparticles studded with the same proteins that comprise the virus's distinctive surface spikes. In addition to being the reason why these are called coronaviruses - corona is Latin for "crown" - these spikes facilitate infection by fusing to a host cell and creating a passageway for the viral genome to enter and hijack the cell's machinery to produce more viruses. The spikes can also be used as antigens, which means their presence in the body is what can trigger an immune response.

Nanoparticle vaccines balance the effectiveness of viral-based vaccines with the safety and ease-of-production of subunit vaccines. Vaccines that use viruses to deliver the antigen are often more effective than vaccines that contain only isolated parts of a virus. However, they can take longer to produce, need to be refrigerated and are more likely to cause side effects. Nucleic acid vaccines - like the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines that have recently been authorized for emergency use by the FDA - are even faster to produce than nanoparticle vaccines but they are expensive to manufacture and may require multiple doses. Initial tests in mice suggest that the Stanford nanoparticle vaccine could produce COVID-19 immunity after just one dose.

The researchers are also hopeful that it could be stored at room temperature and are investigating whether it could be shipped and stored in a freeze-dried, powder form. By comparison, the vaccines that are farthest along in development in the United States all need to be stored at cold temperatures, ranging from approximately 8 to -70 degrees Celsius (46 to -94 degrees Fahrenheit).

"This is really early stage and there is still lots of work to be done," said Abigail Powell, a former postdoctoral scholar in the Kim lab and lead author of the paper. "But we think it is a solid starting point for what could be a single-dose vaccine regimen that doesn't rely on using a virus to generate protective antibodies following vaccination."

The researchers are continuing to improve and fine-tune their vaccine candidate, with the intention of moving it closer to initial clinical trials in humans.

Spikes and nanoparticles The spike protein from SARS-CoV-2 is quite large, so scientists often formulate abridged versions that are simpler to make and easier to use. After closely examining the spike, Kim and his team chose to remove a section near the bottom.

To complete their vaccine, they combined this shortened spike with nanoparticles of ferritin - an iron-containing protein - which has been previously tested in humans. Before the pandemic, Powell had been working with these nanoparticles to develop an Ebola vaccine. Together with scientists at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the researchers used cryo-electron microscopy to get a 3D image of the spike ferritin nanoparticles in order to confirm that they had the proper structure.

For the mouse tests, the researchers compared their shortened spike nanoparticles to four other potentially useful variations: nanoparticles with full spikes, full spikes or partial spikes without nanoparticles, and a vaccine containing just the section of the spike that binds to cells during infection. Testing the effectiveness of these vaccines against actual SARS-CoV-2 virus would have required the work to be done in a Biosafety Level 3 lab, so the researchers instead used a safer pseudo-coronavirus that was modified to carry SARS-CoV-2's spikes.

The researchers determined the potential effectiveness of each vaccine by monitoring levels of neutralizing antibodies. Antibodies are blood proteins produced in response to antigens; neutralizing antibodies are the specific subset of antibodies that actually act to prevent the virus from invading a host cell.

After a single dose, the two nanoparticle vaccine candidates both resulted in neutralizing antibody levels at least twice as high as those seen in people who have had COVID-19, and the shortened spike nanoparticle vaccine produced a significantly higher neutralizing response than the binding spike or the full spike (non-nanoparticle) vaccines. After a second dose, mice that had received the shortened spike nanoparticle vaccine had the highest levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Looking back at this project, Powell estimates that the time from inception to the first mouse studies was about four weeks. "Everybody had a lot of time and energy to devote to the same scientific problem," she said. "It is a very unique scenario. I don't really expect I'll ever encounter that in my career again."

"What's happened in the past year is really fantastic, in terms of science coming to the fore and being able to produce multiple different vaccines that look like they're showing efficacy against this virus," said Kim, who is senior author of the paper. "It normally takes a decade to make a vaccine, if you're even successful. This is unprecedented."

Vaccine access Although the team's new vaccine is intended specifically for populations that may have more difficulty accessing other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, it is possible, given the rapid progress of other vaccine candidates, that it will not be needed to address the current pandemic. In that case, the researchers are prepared to pivot again and pursue a more universal coronavirus vaccine to immunize against SARS-CoV-1, MERS, SARS-CoV-2 and future coronaviruses that are not yet known.

"Vaccines are one of the most profound achievements of biomedical research. They are an incredibly cost-effective way to protect people against disease and save lives," said Kim. "This coronavirus vaccine is part of work we're already doing - developing vaccines that are historically difficult or impossible to develop, like an HIV vaccine - and I'm glad that we're in a situation where we could potentially bring something to bear if the world needs it."

INFORMATION:

Additional Stanford co-authors include Kaiming Zhang, research scientist in bioengineering; Mrinmoy Sanyal, research scientist in biochemistry; Shaogeng Tang, postdoctoral fellow in biochemistry; Payton Weidenbacher, graduate student in chemistry; Shanshan Li, postdoctoral researchers in bioengineering; Tho Pham, clinical assistant professor in pathology at Stanford Medicine (also affiliated with the Stanford Blood Center in Palo Alto); and Wah Chiu, the Wallenberg-Bienenstock Professor at Stanford and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and professor of bioengineering and of microbiology and immunology. A researcher from Chan Zuckerberg Biohub is also a co-author. Kim is a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI) and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and a faculty fellow of Stanford ChEM-H. He is also affiliated with the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub. Chiu is a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and a faculty fellow of Stanford ChEM-H.

This work was funded by MCHRI, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Virginia and D. K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research and Chan Zuckerberg Biohub.