We hear what we expect to hear

2021-01-08

(Press-News.org) Humans depend on their senses to perceive the world, themselves and each other. Despite senses being the only window to the outside world, people do rarely question how faithfully they represent the external physical reality. During the last 20 years, neuroscience research has revealed that the cerebral cortex constantly generates predictions on what will happen next, and that neurons in charge of sensory processing only encode the difference between our predictions and the actual reality.

A team of neuroscientists of TU Dresden headed by Prof Dr Katharina von Kriegstein presents new findings that show that not only the cerebral cortex, but the entire auditory pathway, represents sounds according to prior expectations.

For their study, the team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain responses of 19 participants while they were listening to sequences of sounds. The participants were instructed to find which of the sounds in the sequence deviated from the others. Then, the participants' expectations were manipulated so that they would expect the deviant sound in certain positions of the sequences. The neuroscientists examined the responses elicited by the deviant sounds in the two principal nuclei of the subcortical pathway responsible for auditory processing: the inferior colliculus and the medial geniculate body. Although participants recognised the deviant faster when it was placed on positions where they expected it, the subcortical nuclei encoded the sounds only when they were placed in unexpected positions.

These results can be best interpreted in the context of predictive coding, a general theory of sensory processing that describes perception as a process of hypothesis testing. Predictive coding assumes that the brain is constantly generating predictions about how the physical world will look, sound, feel, and smell like in the next instant, and that neurons in charge of processing our senses save resources by representing only the differences between these predictions and the actual physical world.

Dr Alejandro Tabas, first author of the publication, states on the findings: "Our subjective beliefs on the physical world have a decisive role on how we perceive reality. Decades of research in neuroscience had already shown that the cerebral cortex, the part of the brain that is most developed in humans and apes, scans the sensory world by testing these beliefs against the actual sensory information. We have now shown that this process also dominates the most primitive and evolutionary conserved parts of the brain. All that we perceive might be deeply contaminated by our subjective beliefs on the physical world."

These new results open up new ways for neuroscientists studying sensory processing in humans towards the subcortical pathways. Perhaps due to the axiomatic belief that subjectivity is inherently human, and the fact that the cerebral cortex is the major point of divergence between the human and other mammal's brains, little attention has been paid before to the role that subjective beliefs could have on subcortical sensory representations.

Given the importance that predictions have on daily life, impairments on how expectations are transmitted to the subcortical pathway could have profound repercussion in cognition. Developmental dyslexia, the most wide-spread learning disorder, has already been linked to altered responses in subcortical auditory pathway and to difficulties on exploiting stimulus regularities in auditory perception. The new results could provide with a unified explanation of why individuals with dyslexia have difficulties in the perception of speech, and provide clinical neuroscientists with a new set of hypotheses on the origin of other neural disorders related to sensory processing.

INFORMATION:

Original publication:

Alejandro Tabas, Glad Mihai, Stefan Kiebel, Robert Trampel, Katharina von Kriegstein: Abstract rules drive adaptation in the subcortical sensory pathway. eLife 2020;9:e64501 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.64501

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-08

In a study published in Physical Review Letters, the team led by academician GUO Guangcan from University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) made progress in high dimensional quantum teleportation. The researchers demonstrated the teleportation of high-dimensional states in a three-dimensional six-photon system.

To transmit unknown quantum states from one location to another, quantum teleportation is one of the key technologies to realize the long-distance transmission.

Compared with two-dimensional ...

2021-01-08

In a study published in Advanced Materials, the researchers from Hefei National Laboratory for Physical Sciences at the Microscale, the University of Science and Technology of China of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, using an electron-proton co-doping strategy, invented a new metal-like semiconductor material with excellent plasmonic resonance performance. This material achieves a metal-like ultrahigh free-carrier concentration that leads to strong and tunable plasmonic field.

Plasmonic materials are widely used in the fields including microscopy, sensing, optical computing and photovoltaics. Most common plasmonic materials are gold and silver. Some other materials ...

2021-01-08

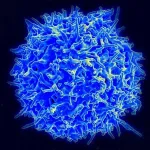

Scientists at the University of Southampton's Centre for Cancer Immunology have gained new insight into how the immune system can be better used to find and kill cancer cells.

Working with BioInvent International, a team led by Professor Mark Cragg and Dr Jane Willoughby from the Antibody and Vaccine Group, based at the Centre, have shown that antibodies, designed to target the molecule OX40, give a more active immune response when they bind closer to the cell membrane and can be modified to attack cancer in different ways.

OX40 is a 'co-receptor' that helps to stimulate the production of helper and killer T-cells during an immune ...

2021-01-08

When Michigan State University's Gemma Reguera first proposed her new research project to the National Science Foundation, one grant reviewer responded that the idea was not "environmentally relevant."

As other reviewers and the program manager didn't share this sentiment, NSF funded the proposal. And, now, Reguera's team has shown that microbes are capable of an incredible feat that could help reclaim a valuable natural resource and soak up toxic pollutants.

"The lesson is that we really need to think outside the box, especially in biology. We just know the tip of the iceberg. Microbes have been on earth for billions of years, and to think that they can't do something precludes us from so many ideas and applications," said Reguera, a professor in ...

2021-01-08

Maize has a significantly higher productivity rate compared with many other crops. The particular leaf anatomy and special form of photosynthesis (referred to as 'C4') developed during its evolution allow maize to grow considerably faster than comparable plants. As a result, maize needs more efficient transport strategies to distribute the photoassimilates produced during photosynthesis throughout the plant.

Researchers at HHU have now discovered a phloem loading mechanism that has not been described before - the bundle sheath surrounding the vasculature as the place for the actual transport of compounds such as sugars or amino acids. The development of this mechanism could have been ...

2021-01-08

A unifying explanation of the cause of autism and the reason for its rising prevalence has eluded scientists for decades, but a theoretical model published in the journal Medical Hypotheses describes the cause as a combination of socially valued traits, common in autism, and any number of co-occurring disabilities.

T.A. Meridian McDonald, PhD, a research instructor in Neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, has spent 25 years researching autism, from a time she could read literally every research paper on the topic in the 1990s until now, when there is an overload of such studies.

"Up until now there have been a lot of theories about the possible causes ...

2021-01-08

In a letter published in the December issue of the American Heart Association's medical journal Circulation a group of researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) dispute the most recent findings of the incidence of myocarditis in athletes with a history of COVID-19.

The Vanderbilt study, COVID-19 Myocardial Pathology Evaluation in AthleTEs with Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (COMPETE CMR), found a much lower degree of myocarditis in athletes than what was previously reported in other studies.

"The differences in the findings are extremely important. The whole world paused after seeing the alarmingly high rates of myocardial inflammation and edema initially published," said ...

2021-01-08

Across the world, health care workers and high-risk groups are beginning to receive COVID-19 vaccines, offering hope for a return to normalcy amidst the pandemic. However, the vaccines authorized for emergency use in the U.S. require two doses to be effective, which can create problems with logistics and compliance. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Central Science have developed a nanoparticle vaccine that elicits a virus-neutralizing antibody response in mice after only a single dose.

The primary target for COVID-19 vaccines is the spike protein, which is necessary for SARS-CoV-2's entry into ...

2021-01-08

In 2020, astronomers added a new member to an exclusive family of exotic objects with the discovery of a magnetar. New observations from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory help support the idea that it is also a pulsar, meaning it emits regular pulses of light.

Magnetars are a type of neutron star, an incredibly dense object mainly made up of tightly packed neutron, which forms from the collapsed core of a massive star during a supernova.

What sets magnetars apart from other neutron stars is that they also have the most powerful known magnetic fields in the universe. For context, the strength of our planet's magnetic field has a value of about one Gauss, while a refrigerator magnet measures about ...

2021-01-08

UC San Francisco scientists have discovered a new way to control the immune system's "natural killer" (NK) cells, a finding with implications for novel cell therapies and tissue implants that can evade immune rejection. The findings could also be used to enhance the ability of cancer immunotherapies to detect and destroy lurking tumors.

The study, published January 8, 2021 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, addresses a major challenge for the field of regenerative medicine, said lead author Tobias Deuse, MD, the Julien I.E. Hoffman, MD, Endowed Chair in Cardiac Surgery in the UCSF Department of Surgery.

"As a cardiac surgeon, I would love to put myself out of business by being able to implant healthy cardiac ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] We hear what we expect to hear