The study, published January 8, 2021 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, addresses a major challenge for the field of regenerative medicine, said lead author Tobias Deuse, MD, the Julien I.E. Hoffman, MD, Endowed Chair in Cardiac Surgery in the UCSF Department of Surgery.

"As a cardiac surgeon, I would love to put myself out of business by being able to implant healthy cardiac cells to repair heart disease," said Deuse, who is interim chair and director of minimally invasive cardiac surgery in the Division of Adult Cardiothoracic Surgery. "And there are tremendous hopes to one day have the ability to implant insulin-producing cells in patients with diabetes or to inject cancer patients with immune cells engineered to seek and destroy tumors. The major obstacle is how to do this in a way that avoids immediate rejection by the immune system."

Deuse and Sonja Schrepfer, MD, PhD, also a professor in the Department of Surgery's Transplant and Stem Cell Immunobiology Laboratory, study the immunobiology of stem cells. They are world leaders in a growing scientific subfield working to produce "hypoimmune" lab-grown cells and tissues -- capable of evading detection and rejection by the immune system. One of the key methods for doing this is to engineer cells with molecular passcodes that activate immune cell "off switches" called immune checkpoints, which normally help prevent the immune system from attacking the body's own cells and modulate the intensity of immune responses to avoid excess collateral damage.

Schrepfer and Deuse recently used gene modification tools to engineer hypoimmune stem cells in the lab that are effectively invisible to the immune system. Notably, as well as avoiding the body's learned or "adaptive" immune responses, these cells could also evade the body's automatic "innate" immune response against potential pathogens. To achieve this, the researchers adapted a strategy used by cancer cells to keep innate immune cells at bay: They engineered their cells to express significant levels of a protein called CD47, which shuts down certain innate immune cells by avtivating a molecular switch found on these cells, called SIRPα. Their success became part of the founding technology of Sana Biotechnology, Inc, a company co-founded by Schrepfer, who now directs a team developing a platform based on these hypoimmune cells for clinical use.

But the researchers were left with a mystery on their hands -- the technique was more successful than predicted. In particular, the field was puzzled that such engineered hypoimmune cells were able to deftly evade detection by NK cells, a type of innate immune cell that isn't supposed to express a SIRPα checkpoint at all.

NK cells are a type of white blood cell that acts as an immunological first responder, quickly detecting and destroying any cells without proper molecular ID proving they are "self" -- native body cells or at least permanent residents -- which takes the form of highly individualized molecules called MHC class I (MHC-I). When MHC-I is artificially knocked out to prevent transplant rejection, the cells become susceptible to accelerated NK cell killing, an immunological rejection that no one in the field had yet succeeded in inhibiting fully. Deuse and Schrepfer's 2019 data, published in Nature Biotechnology, suggested they might have stumbled upon an off switch that could be used for that purpose.

"All the literature said that NK cells don't have this checkpoint, but when we looked at cells from human patients in the lab we found SIRPα there, clear as day," Schrepfer recalled. "We can clearly demonstrate that stem cells we engineer to overexpress CD47 are able to shut down NK cells through this pathway."

To explore their data, Deuse and Schrepfer approached Lewis Lanier, PhD, a world expert in NK cell biology. At first Lanier was sure there must be some mistake, because several groups had looked for SIRPα in NK cells already and it wasn't there. But Schrepfer was confident in her team's data.

"Finally it hit me," Schrepfer said. "Most studies looking for checkpoints in NK cells were done in immortalized lab-grown cell lines, but we were studying primary cells directly from human patients. I knew that must be the difference."

Further examination revealed that NK cells only begin to express SIRPα after they are activated by certain immune signaling molecules called cytokines. As a result, the researchers realized, this inducible immune checkpoint comes into effect only in already inflammatory environments and likely functions to modulate the intensity of NK cells' attack on cells without proper MHC class I identification.

"NK cells have been a major barrier to the field's growing interest in developing universal cell therapy products that can be transplanted "off the shelf" without rejection, so these results are extremely promising," said Lanier, chair and J. Michael Bishop Distinguished Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

In collaboration with Lanier, Deuse and Schrepfer comprehensively documented how CD47-expressing cells can silence NK cells via SIRPα. While other approaches can silence some NK cells, this was the first time anyone has been able to inhibit them completely. Notably, the team found that NK cells' sensitivity to inhibition by CD47 is highly species-specific, in line with its function in distinguishing "self" from potentially dangerous "other".

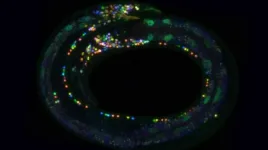

As a demonstration of this principle, the team engineered adult human stem cells with the rhesus macaque version of CD47, then implanted them into rhesus monkeys, where they successfully activated SIRPα in the monkeys' NK cells, and avoided killing the transplanted human cells. In the future the same procedure could be performed in reverse, expressing human CD47 in pig cardiac cells, for instance, to prevent them from activating NK cells when transplanted into human patients.

"Currently engineered CAR T cell therapies for cancer and fledgling forms of regenerative medicine all rely on being able to extract cells from the patient, modify them in the lab, and then put them back in the patient. This avoids rejection of foreign cells, but is extremely laborious and expensive," Schrepfer said. "Our goal in establishing a hypoimmune cell platform is to create off-the shelf products that can be used to treat disease in all patients everywhere."

The findings could also have implications for cancer immunotherapy, as a way of boosting existing therapies that attempt to overcoming the immune checkpoints cancers use to evade immune detection. "Many tumors have low levels of self-identifying MHC-I protein and some compensate by overexpressing CD47 to keep immune cells at bay," said Lanier, who is director of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. "This might be the sweet spot for antibody therapies that target CD47."

INFORMATION:

Authors: The study's lead authors were Deuse and UCSF TSI lab research scientist Xiaomeng Hu; Lanier and Schrepfer were the study's senior authors, and Schrepfer is corresponding author. Other authors were Sean Agbor-Enoh of The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); Moon K. Jang at the NHLBI; Hannah Valantine at Stanford; Malik Alawi and Ceren Saygi of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany; Alessia Gravina, Grigol Tediashvili, and Vinh Q. Nguyen of UCSF; and Yuan Liu of Georgia State University.

Funding: The research and researchers are supported by NHLBI (R01HL140236), the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, and the US National Institutes of Health (NIH P30 DK063720 NIH S10 1S10OD021822-01).

Disclosures: Deuse is scientific co-founder and Schrepfer is scientific founder and Senior Vice President of Sana Biotechnology Inc. Xiaomeng Hu is now senior scientist at Sana Biotechnology Inc. Neither reagents nor any funding from Sana Biotechnology Inc. was used in this study. UCSF has filed patent applications that cover these inventions.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf