(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - Scientists have figured out a cheaper, more efficient way to conduct a chemical reaction at the heart of many biological processes, which may lead to better ways to create biofuels from plants.

Scientists around the world have been trying for years to create biofuels and other bioproducts more cheaply; this study, published today in the journal Scientific Reports, suggests that it is possible to do so.

"The process of converting sugar to alcohol has to be very efficient if you want to have the end product be competitive with fossil fuels," said Venkat Gopalan, a senior author on the paper and professor of chemistry and biochemistry at The Ohio State University. "The process of how to do that is well-established, but the cost makes it not competitive, even with significant government subsidies. This new development is likely to help lower the cost."

At the heart of their discovery: A less expensive and simpler method to create the "helper molecules" that allow carbon in cells to be turned into energy. Those helper molecules (which chemists call cofactors) are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and its derivative (NADPH). These cofactors in their reduced forms have long been known to be a key part of turning sugar from plants into butanol or ethanol for fuels. Both cofactors also play an important role in slowing the metabolism of cancer cells and have been a target of treatment for some cancers.

But NADH and NADPH are expensive.

"If you can cut the production cost in half, that would make biofuels a very attractive additive to make flex fuels with gasoline," said Vish Subramaniam, a senior author on the paper and recently retired professor of engineering at Ohio State. "Butanol is often not used as an additive because it's not cheap. But if you could make it cheaply, suddenly the calculus would change. You could cut the cost of butanol in half, because the cost is tied up in the use of this cofactor."

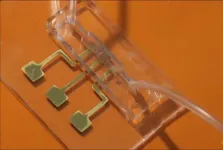

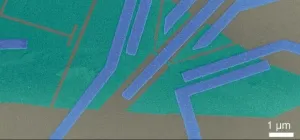

To create these reduced cofactors in the lab, the researchers built an electrode by layering nickel and copper, two inexpensive elements. That electrode allowed them to recreate NADH and NADPH from their corresponding oxidized forms. In the lab, the researchers were able to use NADPH as a cofactor in producing an alcohol from another molecule, a test they did intentionally to show that ¬the electrode they built could help convert biomass - plant cells - to biofuels. This work was performed by Jonathan Kadowaki and Travis Jones, two mechanical and aerospace engineering graduate students in the Subramaniam lab, and Anindita Sengupta, a postdoctoral researcher in the Gopalan lab.

But because NADH and NADPH are at the heart of so many energy conversion processes inside cells, this discovery could aid other synthetic applications.

Subramaniam's previous work showed that electromagnetic fields can slow the spread of some breast cancers. He retired from Ohio State on Dec. 31.

This finding is connected, he said: It might be possible for scientists to more easily and affordably control the flow of electrons in some cancer cells, potentially slowing their growth and ability to metastasize.

Subramaniam also has spent much of his later scientific career exploring if scientists could create a synthetic plant, something that would use the energy of the sun to convert carbon dioxide into oxygen. On a large enough scale, he thought, such a creation could potentially reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and help address climate change.

"I've always been interested in that question of, 'Can we make a synthetic plant? Can we make something that can solve this global warming problem with carbon dioxide?'" Subramaniam said. "If it's impractical to do it with plants because we keep destroying them via deforestation, are there other inorganic ways of doing this?"

This discovery could be a step toward that goal: Plants use NADPH to turn carbon dioxide into sugars, which eventually become oxygen through photosynthesis. Making NADPH more accessible and more affordable could make it possible to produce an artificial photosynthesis reaction.

But its most likely and most immediate application is for biofuels.

That the researchers came together for this scientific inquiry was rare: Biochemists and engineers don't often conduct joint laboratory research.

Gopalan and Subramaniam met at a brainstorming session hosted by Ohio State's Center for Applied Plant Sciences (CAPS), where they were told to think about "big sky ideas" that might help solve some of society's biggest problems. Subramaniam told Gopalan about his work with electrodes and cells, "and the next thing we knew, we were discussing this project," Gopalan said. "We certainly would not have talked to each other if it were not for the CAPS workshop."

INFORMATION:

CONTACT: Venkat Gopalan, gopalan.5@osu.edu

Written by Laura Arenschield, arenschield.2@osu.edu

The mitochondrial ATP synthase is energy-converting macromolecular machine that uses the electrochemical potential across the bioenergetic membrane called cristae. This potential is maintained via a membrane curvature that is induced by ATP synthase assembled in dimers. The dimers shaping the bioenergetic membrane were thought to be universal across the eukaryotic organisms. Two newly published cryo-EM studies by Kock-Flygaard et al and Mühleip et al from Alexey Amunts lab, identify different types of ATP synthase organization.

The structure of the ATP synthase from ciliates revealed a dimer, which unlike in all the previously investigated complexes, the two ...

New Curtin University research has found a dramatic increase in people's trust in government in Australia and New Zealand as a result of the COVID pandemic.

Published in the Australian Journal of Public Administration, the team surveyed people in Australia and New Zealand in July 2020 and found confidence in public health scientists to also be high and for this trust to be manifested in higher usage of government COVID phone apps.

Lead researcher Professor Shaun Goldfinch, ANZSOG WA Government Chair in Public Administration and Policy based at the John Curtin Institute of Public Policy at Curtin said the management of the pandemic by authorities led to a dramatic increase in trust in government.

"Using an online panel, we surveyed a representative sample of 500 people each in Australia ...

An important and still unanswered question is how new genes that cause antibiotic resistance arise. In a new study, Swedish and American researchers have shown how new genes that produce resistance can arise from completely random DNA sequences. The results have been published in the journal PLOS Genetics.

Antibiotic resistance is a major global problem and the spread of resistant bacteria causes disease and death, and constitutes a major cost to society. The most common way for bacteria to develop resistance is by taking up various types of resistance genes from other bacteria. These genes encode proteins (peptides) that can lead to resistance by: (i) deactivating the antibiotic, (ii) reducing its concentration, or (iii) altering ...

PITTSBURGH--Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University report findings on an advanced nanomaterial-based biosensing platform that detects, within seconds, antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to testing, the platform will help to quantify patient immunological response to the new vaccines with precision.

The results were published this week in the journal Advanced Materials. Carnegie Mellon's collaborators included the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) and the UPMC.

The testing platform identifies the presence of two of the virus' antibodies, spike S1 protein and receptor binding domain (RBD), in a ...

Leg amputees are often not satisfied with their prosthesis, even though the sophisticated prostheses are becoming available. One important reason for this is that they perceive the weight of the prosthesis as too high, despite the fact that prosthetic legs are usually less than half the weight of a natural limb. Researchers led by Stanisa Raspopovic, a professor at the Department of Health Sciences and Technology, have now been able to show that connecting the prostheses to the nervous system helps amputees to perceive the prosthesis weight as lower, which ...

Stay awake too long, and thinking straight can become extremely difficult. Thankfully, a few winks of sleep is often enough to get our brains functioning up to speed again. But just when and why did animals start to require sleep? And is having a brain even a prerequisite?

In a study that could help to understand the evolutional origin of sleep in animals, an international team of researchers has shown that tiny, water-dwelling hydras not only show signs of a sleep-like state despite lacking central nervous systems but also respond to molecules associated ...

Since 2006, a fungal disease called white-nose syndrome has caused sharp declines in bat populations across the eastern United States. The fungus that causes the disease, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, thrives in subterranean habitats where bats hibernate over the winter months.

Bats roosting in the warmest sites have been hit particularly hard, since more fungus grows on their skin, and they are more likely to die from white-nose syndrome, according to a new study by researchers at Virginia Tech.

But instead of avoiding these warm and deadly sites, bats continue to use them year after year. The reason? Bats are mistakenly preferring sites where fungal growth is ...

An invisible flow of groundwater seeps into the ocean along coastlines all over the world. Scientists have tended to disregard its contributions to ocean chemistry, focusing on the far greater volumes of water and dissolved material entering the sea from rivers and streams, but a new study finds groundwater discharge plays a more significant role than had been thought.

The new findings, published January 8 in Nature Communications, have implications for global models of biogeochemical cycles and for the interpretation of isotope records of Earth's climate history.

"It's really hard to characterize groundwater discharge, so it has been a source of uncertainty in the modeling of global cycles," said first author Kimberley Mayfield, who led the study as ...

Pleiotropy analysis, which provides insight on how individual genes result in multiple characteristics, has become increasingly valuable as medicine continues to lean into mining genetics to inform disease treatments. Privacy stipulations, though, make it difficult to perform comprehensive pleiotropy analysis because individual patient data often can't be easily and regularly shared between sites. However, a statistical method called Sum-Share, developed at Penn Medicine, can pull summary information from many different sites to generate significant insights. In a test of the method, published in Nature Communications, Sum-Share's developers were able to detect more than 1,700 DNA-level variations that ...

A joint group of scientists from Finland, Russia, China and the USA have demonstrated that temperature difference can be used to entangle pairs of electrons in superconducting structures. The experimental discovery, published in Nature Communications, promises powerful applications in quantum devices, bringing us one step closer towards applications of the second quantum revolution.

The team, led by Professor Pertti Hakonen from Aalto University, has shown that the thermoelectric effect provides a new method for producing entangled electrons in a new device. "Quantum entanglement is the cornerstone of the novel quantum technologies. This concept, however, has puzzled many physicists over the years, including Albert Einstein who worried a lot about the ...