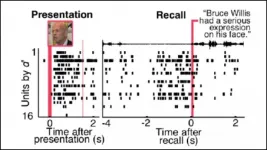

The body's defense system generally does not recognize cancer cells as dangerous. To correct this sometimes fatal error, researchers are investigating a clever new idea, one that involves taking a handful of immune cells from cancer patients and "upgrading" them in the laboratory so that they recognize certain surface proteins in the malignant cells. The researchers then multiply the immune cells and inject them back into the patients' blood - setting them off on a journey through the body to detect and attack all cancer cells in a targeted way.

In fact, the first treatments based on this idea have already been approved: So-called CAR T cells have been used in Europe since 2018, particularly in patients with B-cell lymphomas for whom conventional cancer therapies have not worked.

T cells are like the immune system's police force. The abbreviation CAR stands for "chimeric antigen receptor" - meaning that the cellular police force is equipped with a new, laboratory-designed special antenna that targets a surface protein on the cancer cells. Thanks to this antenna, a small number of T cells can round up a large number of cancer cells and destroy them. Ideally, the CAR T cells patrol the body for weeks, months or even years and thus prevent tumor relapse.

A kind of signpost for B cells

Until now, the antenna on the CAR T cells was primarily directed against the protein CD19, which B cells - a type of immune cells - carry on their surface. Yet this form of therapy is by no means effective in all patients. A team led by Dr. Uta Hoepken, head of the Microenvironmental Regulation in Autoimmunity and Cancer Lab at the Max Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC), has now developed a new twist on this therapy that sensitizes the T cells in the laboratory to a different identifying feature: the B-cell homing protein CXCR5.

"CXCR5 was first described at the MDC more than 20 years ago, and I have been studying this protein myself for almost as long," says Hoepken. "I am therefore very pleased that we have now succeeded in using CXCR5 to effectively combat non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, such as follicular and mantle cell lymphoma as well as chronic lymphocytic leukemias, in the laboratory." This protein is a receptor that helps mature B cells move from the bone marrow - where they are produced - to immune system organs such as the lymph nodes and spleen. "Without the receptor, the B cells would not find their way to their target site, the B-cell follicles of these lymphoid organs," Hoepken explains.

A well-suited target

"All mature B cells, including malignant ones, carry this receptor on their surface. So it seemed to us to be well suited to detect B-cell tumors - thereby enabling CAR-T cells directed against CXCR5 to attack the cancer," says Janina Pfeilschifter, a PhD student in Hoepken's team. She and Dr. Mario Bunse from the same research group are the lead authors of the paper, which appeared in the journal Nature Communications. "In our study, we have shown through experiments with human cancer cells and two mouse models that this immunotherapy is most likely safe and very effective," says Pfeilschifter.

The new approach may be particularly well suited for patients with a follicular lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). "Both types of cancer involve not only B cells but also follicular T helper cells, which also carry CXCR5 on their surface," Bunse explains. The special antenna for the identifying feature, the CXCR5-CAR, was generated by Dr. Julia Bluhm during her time as a PhD student in the MDC's Translational Tumorimmunology Lab, which is headed by physician Dr. Armin Rehm. He and Hoepken are the corresponding authors of the study.

First successes in the petri dish

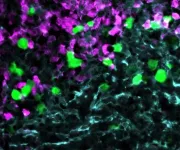

Pfeilschifter and Bunse first showed that various human cells, for example, from blood vessels, the gut and the brain, do not carry the CXCR5 receptor on their surface and are therefore not attacked in the petri dish by T cells equipped with CXCR5-CAR. "This is important to prevent unexpected organ damage from occurring during therapy," Pfeilschifter explains. In contrast, experiments with human tumor cell lines showed that malignant B cells from very different forms of B-non-Hodgkin's lymphoma all display the receptor.

Professor Joerg Westermann, from the Division of Hematology, Oncology and Tumor Immunology in the Medical Department of Charite - Universitaetsmedizin Berlin at the Campus Virchow Clinic, also provided the team with tumor cells from patients with CLL or B-non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. "There, too, we were able to detect CXCR5 on all B-lymphoma cells and follicular T helper cells," Pfeilschifter says. When she and Bunse placed the tumor cells in the petri dish together with the CXCR5-targeted CAR T cells, almost all of the malignant B and T helper cells disappeared from the tissue sample after 48 hours.

Mice with leukemia were cured

The researchers also tested the new procedure on two mouse models. "The CAR T cells are infused into the blood of cancer patients," Hoepken says. "So animal research is needed to show that the cells home to the niches where the cancer resides, multiply there and then do their job effectively."

One model consisted of animals with a severely suppressed immune system, which could therefore be treated with human CAR T cells without causing rejection reactions. "We also developed a pure mouse model for CLL specifically for the current study," Bunse reports. "We administered mouse CAR T cells against CXCR5 to these animals by infusion and were able to eliminate mature B cells and T helper cells, including malignant ones, from the B-cell follicles of the lymphoid organs."

The researchers discovered no serious side effects in the mice. "We know from experience with cancer patients that CAR T-cell therapy increases the risk of infection for a few months," Rehm says. But in practice this side effect is almost always easily managed.

A clinical trial is in the works

"No laboratory can tackle such a study on its own," Hoepken emphasizes. "It has only come about thanks to a successful collaboration between many colleagues at the MDC and Charite." For her, the study is the first step toward creating a "living drug" - similar to other cellular immunotherapies being developed at MDC. "We are already cooperating with two cancer specialists at Charite and are currently working with them to prepare a phase 1/2 clinical trial," adds Hoepken's colleague Rehm. Both hope that the first patients will begin to benefit from their new CAR-T cell therapy in the near future.

INFORMATION:

The German Jose Carreras Leukemia Foundation has funded the research with around 240,000 euros over a period of three years. The non-profit organization supports forward-looking research projects and infrastructure projects that investigate the causes of leukemia and improve treatment, as well as social projects.

Literature

Mario Bunse, Janina Pfeilschifter et al. (2021): "CXCR5 CAR-T cells simultaneously target B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and tumor-supportive follicular T helper cells". Nature Communications, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-20488-3.

The Max Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

The Max Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) was founded in Berlin in 1992. It is named for the German-American physicist Max Delbrueck, who was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. The MDC's mission is to study molecular mechanisms in order to understand the origins of disease and thus be able to diagnose, prevent and fight it better and more effectively. In these efforts the MDC cooperates with the Charite - Universitaetsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH ) as well as with national partners such as the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and numerous international research institutions. More than 1,600 staff and guests from nearly 60 countries work at the MDC, just under 1,300 of them in scientific research. The MDC is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (90 percent) and the State of Berlin (10 percent), and is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers. http://www.mdc-berlin.de