INFORMATION:

Scientists reveal mechanism that causes irritable bowel syndrome

2021-01-13

(Press-News.org) KU Leuven researchers have identified the biological mechanism that explains why some people experience abdominal pain when they eat certain foods. The finding paves the way for more efficient treatment of irritable bowel syndrome and other food intolerances. The study, carried out in mice and humans, was published in Nature.

Up to 20% of the world's population suffers from the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which causes stomach pain or severe discomfort after eating. This affects their quality of life. Gluten-free and other diets can provide some relief, but why this works is a mystery, since the patients are not allergic to the foods in question, nor do they have known conditions such as coeliac disease.

"Very often these patients are not taken seriously by physicians, and the lack of an allergic response is used as an argument that this is all in the mind, and that they don't have a problem with their gut physiology," says Professor Guy Boeckxstaens, a gastroenterologist at KU Leuven and lead author of the new research. "With these new insights, we provide further evidence that we are dealing with a real disease."

Histamine

His team's laboratory and clinical studies reveal a mechanism that connects certain foods with activation of the cells that release histamine (called mast cells), and subsequent pain and discomfort. Earlier work by Professor Boeckxstaens and his colleagues showed that blocking histamine, an important component of the immune system, improves the condition of people with IBS.

In a healthy intestine, the immune system does not react to foods, so the first step was to find out what might cause this tolerance to break down. Since people with IBS often report that their symptoms began after a gastrointestinal infection, such as food poisoning, the researchers started with the idea that an infection while a particular food is present in the gut might sensitise the immune system to that food.

They infected mice with a stomach bug, and at the same time fed them ovalbumin, a protein found in egg white that is commonly used in experiments as a model food antigen. An antigen is any molecule that provokes an immune response. Once the infection cleared, the mice were given ovalbumin again, to see if their immune systems had become sensitised to it. The results were affirmative: the ovalbumin on its own provoked mast cell activation, histamine release, and digestive intolerance with increased abdominal pain. This was not the case in mice that had not been infected with the bug and received ovalbumin.

A spectrum of food-related immune diseases

The researchers were then able to unpick the series of events in the immune response that connected the ingestion of ovalbumin to activation of the mast cells. Significantly, this immune response only occurred in the part of the intestine infected by the disruptive bacteria. It did not produce more general symptoms of a food allergy.

Professor Boeckxstaens speculates that this points to a spectrum of food-related immune diseases. "At one end of the spectrum, the immune response to a food antigen is very local, as in IBS. At the other end of the spectrum is food allergy, comprising a generalised condition of severe mast cell activation, with an impact on breathing, blood pressure, and so on."

The researchers then went on to see if people with IBS reacted in the same way. When food antigens associated with IBS (gluten, wheat, soy and cow milk) were injected into the intestine wall of 12 IBS patients, they produced localised immune reactions similar to that seen in the mice. No reaction was seen in healthy volunteers.

The relatively small number of people involved means this finding needs further confirmation, but it appears significant when considered alongside the earlier clinical trial showing improvement during treatment of IBS patients with anti-histaminics. "This is further proof that the mechanism we have unravelled has clinical relevance," Professor Boeckxstaens says.

A larger clinical trial of the antihistamine treatment is currently under way. "But knowing the mechanism that leads to mast cell activation is crucial, and will lead to novel therapies for these patients," he goes on. "Mast cells release many more compounds and mediators than just histamine, so if you can block the activation of these cells, I believe you will have a much more efficient therapy."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

High insulin levels during childhood a risk for mental health problems in adulthood, study suggests

2021-01-13

Researchers have shown that the link between physical and mental illness is closer than previously thought. Certain changes in physical health, which are detectable in childhood, are linked with the development of mental illness in adulthood.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge, used a sample of over 10,000 people to study how insulin levels and body mass index (BMI) in childhood may be linked with depression and psychosis in young adulthood.

They found that persistently high insulin levels from mid-childhood were linked with a higher chance of developing psychosis in adulthood. In addition, they found that an increase in BMI around the onset of puberty, was linked with a higher chance of developing depression in adulthood, ...

Shine on: Avalanching nanoparticles break barriers to imaging cells in real time

2021-01-13

Since the earliest microscopes, scientists have been on a quest to build instruments with finer and finer resolution to image a cell's proteins - the tiny machines that keep cells, and us, running. But to succeed, they need to overcome the diffraction limit, a fundamental property of light that long prevented optical microscopes from bringing into focus anything smaller than half the wavelength of visible light (around 200 nanometers or billionths of a meter) - far too big to explore many of the inner-workings of a cell.

For over a century, scientists have experimented with different approaches - from intensive calculations to special lasers and microscopes - to resolve cellular features at ever smaller scales. And ...

Northern lakes at risk of losing ice cover permanently, impacting drinking water

2021-01-13

TORONTO, Jan. 13, 2021 - Close to 5,700 lakes in the Northern Hemisphere may permanently lose ice cover this century, 179 of them in the next decade, at current greenhouse gas emissions, despite a possible polar vortex this year, researchers at York University have found.

Those lakes include large bays in some of the deepest of the Great Lakes, such as Lake Superior and Lake Michigan, which could permanently become ice free by 2055 if nothing is done to curb greenhouse gas emissions or by 2085 with moderate changes.

Many of these lakes that are ...

Medication shows promise for weight loss in patients with obesity, diabetes

2021-01-13

SILVER SPRING, Md.--A new study confirms that treatment with Bimagrumab, an antibody that blocks activin type II receptors and stimulates skeletal muscle growth, is safe and effective for treating excess adiposity and metabolic disturbances of adult patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes.

"These exciting results suggest that there may be a novel mechanism for achieving weight loss with a profound loss of body fat and an increase in lean mass, along with other metabolic benefits," said Steve Heymsfield, MD, FTOS, past president of The Obesity Society and corresponding author of the study. Heymsfield is professor and director of the Metabolism and Body Composition Laboratory at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La.

A ...

KU studies show breakfast can improve basketball shooting performance

2021-01-13

LAWRENCE -- Parents around the world have long told us that breakfast is the most important meal of the day. Soon, basketball coaches may join them.

Researchers at the University of Kansas have published a study showing that eating breakfast can improve a basketball player's shooting performance, sometimes by significant margins. The study, along with one showing that lower body strength and power can predict professional basketball potential, is part of a larger body of work to better understand the science of what makes an elite athlete.

Breakfast and better basketball shooting

Dimitrije Cabarkapa left his native Novi Sad, Serbia, to play basketball at James Madison University. Never a fan of 6 a.m. workouts, he was discussing ...

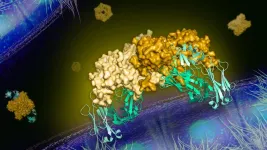

Scientists find antibody that blocks dengue virus

2021-01-13

A team of researchers led by the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Michigan has discovered an antibody that blocks the spread within the body of the dengue virus, a mosquito-borne pathogen that infects between 50 and 100 million people a year. The virus causes what is known as dengue fever, symptoms of which include fever, vomiting and muscle aches, and can lead to more serious illnesses, and even death.

"Protein structures determined at the APS have played a critical role in the development of drugs and vaccines for several diseases, and these new results are key to the development of a potentially effective treatment against flaviviruses." -- Bob Fischetti, group leader with Argonne's X-ray Sciences Division and life sciences ...

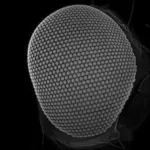

A fly's eye view of evolution

2021-01-13

The fascinating compound eyes of insects consist of hundreds of individual eyes known as "facets". In the course of evolution, an enormous variety of eye sizes and shapes has emerged, often representing adaptations to different environmental conditions. Scientists, led by an Emmy Noether research group at the University of Göttingen, together with scientists from the Andalusian Centre for Developmental Biology (CABD) in Seville, have now shown that these differences can be caused by very different changes in the genome of fruit flies. The study was published ...

Flashing plastic ash completes recycling

2021-01-13

HOUSTON - (Jan. 13, 2021) - Pyrolyzed plastic ash is worthless, but perhaps not for long.

Rice University scientists have turned their attention to Joule heating of the material, a byproduct of plastic recycling processes. A strong jolt of energy flashes it into graphene.

The technique by the lab of Rice chemist James Tour produces turbostratic graphene flakes that can be directly added to other substances like films of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) that better resist water in packaging and cement paste and concrete, dramatically increasing their compressive strength. ...

Pollinators not getting the 'buzz' they need in news coverage

2021-01-13

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- A dramatic decline in bees and other pollinating insects presents a threat to the global food supply, yet it's getting little attention in mainstream news.

That's the conclusion of a study from researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, published this week in a special issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study was based on a search of nearly 25 million news items from six prominent U.S. and global news sources, among them The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Associated Press.

The study found "vanishingly low levels of attention to pollinator population topics" over several decades, even compared with ...

Wetland methane cycling increased during ancient global warming event

2021-01-13

Wetlands are the dominant natural source of atmospheric methane, a potent greenhouse gas which is second only to carbon dioxide in its importance to climate change. Anthropogenic climate change is expected to enhance methane emissions from wetlands, resulting in further warming. However, wetland methane feedbacks were not fully assessed in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report, posing a challenge to meeting the global greenhouse gas mitigation goals set under the Paris Agreement.

To understand how wetland methane cycling may evolve and drive climate feedbacks in the future, scientists are increasingly looking to Earth's past.

"Ice core records indicate ...