(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Images of a protein involved in creating a potent antibiotic reveal the unusual first steps of the antibiotic's synthesis. The improved understanding of the chemistry behind this process, detailed in a new study led by Penn State chemists, could allow researchers to adapt this and similar compounds for use in human medicine.

"The antibiotic thiostrepton is very potent against Gram-positive pathogens and can even target certain breast cancer cells in culture," said Squire Booker, a biochemist at Penn State and investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. "While it has been used topically in veterinary medicine, so far it has been ineffective in humans because it is poorly absorbed. We studied the first steps in thiostrepton's biosynthesis in hopes of eventually being able to hijack certain processes and make analogs of the molecule that might have better medicinal properties. Importantly, this reaction is found in the biosynthesis of numerous other antibiotics, and so the work has the potential to be far reaching."

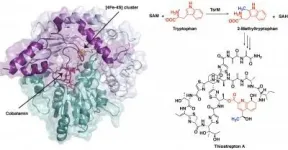

The first step in thiostrepton's synthesis involves a process called methylation. A molecular tag called methyl group, which is important in many biological processes, is added to a molecule of tryptophan, the reaction's substrate. One of the major systems for methylating compounds that are not particularly reactive, like tryptophan, involves a class of enzymes called radical SAM proteins.

"Radical SAM proteins usually use an iron-sulfur cluster to cleave a molecule called S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM), producing a "free radical" or an unpaired electron that helps move the reaction forward," said Hayley Knox, a graduate student in chemistry at Penn State and first author of the paper. "The one exception that we know about so far is the protein involved in the biosynthesis of thiostrepton, called TsrM. We wanted to understand why TsrM doesn't do radical chemistry, so we used an imaging technique called X-ray crystallography to investigate its structure at several stages throughout its reaction."

In all radical SAM proteins characterized to date, SAM binds directly to the iron-sulfur cluster, which helps to fragment the molecule to produce the free radical. However, the researchers found that the site where SAM would typically bind is blocked in TsrM.

"This is completely different from any other radical SAM protein," said Booker. "Instead, the portion of SAM that binds to the cluster associates with the tryptophan substrate and plays a key role in the reaction, in what is called substrate-assisted catalysis."

The researchers present their results in an article appearing Jan. 18 in the journal Nature Chemistry.

In solving the structure, the researchers were able to infer the chemical steps during the first part of thiostrepton's biosynthesis, when tryptophan is methylated. In short, the methyl group from SAM transfers to a part of TsrM called cobalamin. Then, with the help of an additional SAM molecule, the methyl group transfers to tryptophan, regenerating free cobalamin and producing the methylated substrate, which is required for the next steps in synthesizing the antibiotic.

"Cobalamin is the strongest nucleophile in nature, which means it is highly reactive," said Knox. "But the substrate tryptophan is weakly nucleophilic, so a big question is how cobalamin could ever be displaced. We found that an arginine residue sits under the cobalamin and destabilizes the methyl-cobalamin, allowing tryptophan to displace cobalamin and become methylated."

Next the researchers plan to study other cobalamin-dependent radical SAM proteins to see if they operate in similar ways. Ultimately, they hope to find or create analogs of thiostrepton that can be used in human medicine.

"TsrM is clearly unique in terms of known cobalamin-dependent radical SAM proteins and radical SAM proteins in general," said Booker. "But there are hundreds of thousands of unique sequences of radical SAM enzymes, and we still don't know what most of them do. As we continue to study these proteins, we may be in store for many more surprises."

INFORMATION:

Squire Booker is an Evan Pugh University Professor of Chemistry and of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Holder of the Eberly Distinguished Family Chair in Science at Penn State. In addition to Booker and Knox, the research team at Penn State includes graduate students at the time of the research Anthony Blaszczyk and Erica Schwalm; postdoctoral researcher Arnab Mukherjee; and Assistant Research Professor of Chemistry Bo Wang. The team also includes Percival Yang-Ting Chen and Catherine Drennan at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and former Penn State graduate student Tyler Grove, now an assistant professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Penn State Eberly College of Science, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

HOUSTON — In an effort to address a major challenge when analyzing large single-cell RNA-sequencing datasets, researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have developed a new computational technique to accurately differentiate between data from cancer cells and the variety of normal cells found within tumor samples. The work was published today in Nature Biotechnology.

The new tool, dubbed CopyKAT (copy number karyotyping of aneuploid tumors), allows researchers to more easily examine the complex data obtained from large single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments, which deliver gene expression data from ...

Mount Sinai researchers have published one of the first studies using a machine learning technique called "federated learning" to examine electronic health records to better predict how COVID-19 patients will progress. The study was published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research - Medical Informatics on January 18.

The researchers said the emerging technique holds promise to create more robust machine learning models that extend beyond a single health system without compromising patient privacy. These models, in turn, can help triage patients and improve the quality of their care.

Federated ...

A research team from the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) has developed a process for the electrolytic treatment of wastewater that degrades microplastics at the source. The results of this research have been published in the Environmental Pollution journal.

Wastewater can carry high concentrations of microplastics into the environment. These small particles of less than 5 mm can come from our clothes, usually as microfibers. Professor Patrick Drogui, who led the study, points out there are currently no established degradation methods to handle this contaminant during wastewater ...

Philadelphia, January 18, 2021 - A new study comparing the incidence of sudden deaths occurring outside the hospital across New York City's highly diverse neighborhoods with the percentage of positive SARS-CoV-19 tests found that increased sudden deaths during the pandemic correlate to the extent of virus infection in a neighborhood. The analysis appears in Heart Rhythm, the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, the Cardiac Electrophysiology Society, and the Pediatric & Congenital Electrophysiology Society, published by Elsevier.

"Our research shows the highly diverse regional distribution of out-of-hospital sudden death during ...

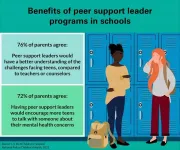

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- An estimated one in five teenagers has symptoms of a mental health disorder such as depression or anxiety, and suicide is the second leading cause of death among teens.

But the first person a teen confides in may not always be an adult - they may prefer to talk to another teen.

And three-quarters of parents in a new national poll think peers better understand teen challenges, compared to teachers or counselors in the school. The majority also agree that peer support leaders at school would encourage more teens to talk with someone about their mental health problems, according to the C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health at Michigan Medicine.

"Peers may provide valuable support for ...

New research examining more than 800,000 traffic stops in Vermont over the course of five years substantiates the term "driving while Black and Brown."

Compared to white drivers, Black and Latinx drivers in Vermont are more likely to be stopped, ticketed, arrested, and searched. But they are less likely to be found with contraband than white drivers. The report finds evidence not only of racial disparities but also racial bias in policing. What's more, a number of these gaps widened over the years examined in the report. With such comprehensive data encompassing the state of Vermont, the authors also found that Vermont police stop cars at a rate ...

A student infected with COVID-19 returning home from university for Christmas would, on average, have infected just less than one other household member with the virus, according to a new model devised by mathematicians at Cardiff University and published in END ...

Variation in consumption of market-acquired foods outside of the traditional diet -- but not in total calories burned daily -- is reliably related to indigenous Amazonian children's body fat, according to a Baylor University study that offers insight into the global obesity epidemic.

"The importance of a poor diet versus low energy expenditure on the development of childhood obesity remains unclear," said Samuel Urlacher, Ph.D., assistant professor of anthropology at Baylor University, CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholar and lead author of the study. "Using gold-standard measures of energy expenditure, we show that relatively lean, rural forager-horticulturalist children in the Amazon spend approximately the same total number of calories each day as their much ...

Spiritualist mediums might be more prone to immersive mental activities and unusual auditory experiences early in life, according to new research.

This might explain why some people and not others eventually adopt spiritualist beliefs and engage in the practice of 'hearing the dead', the study led by Durham University found.

Mediums who "hear" spirits are said to be experiencing clairaudient communications, rather than clairvoyant ("seeing") or clairsentient ("feeling" or "sensing") communications.

The researchers conducted a survey of 65 clairaudient spiritualist mediums from the Spiritualists' National Union and 143 members of the general population in the ...

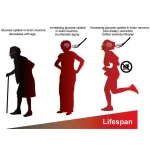

Tokyo, Japan - Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have discovered that fruit flies with genetic modifications to enhance glucose uptake have significantly longer lifespans. Looking at the brain cells of aging flies, they found that better glucose uptake compensates for age-related deterioration in motor functions, and led to longer life. The effect was more pronounced when coupled with dietary restrictions. This suggests healthier eating plus improved glucose uptake in the brain might lead to enhanced lifespans.

The brain is a particularly power-hungry part of our bodies, consuming 20% of the oxygen we take in and 25% of the glucose. That's why it's so important that it can stay powered, ...