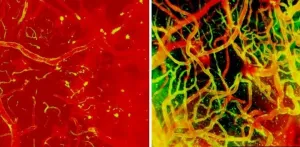

(Press-News.org) Researchers from the National Institutes of Health have discovered Jekyll and Hyde immune cells in the brain that ultimately help with brain repair but early after injury can lead to fatal swelling, suggesting that timing may be critical when administering treatment. These dual-purpose cells, which are called myelomonocytic cells and which are carried to the brain by the blood, are just one type of brain immune cell that NIH researchers tracked, watching in real-time as the brain repaired itself after injury. The study, published in Nature Neuroscience, was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Intramural Research Program at NIH.

"Fixing the brain after injury is a highly orchestrated, coordinated process, and giving a treatment at the wrong time could end up doing more harm than good," said Dorian McGavern, Ph.D., NINDS scientist and senior author of the study.

Cerebrovascular injury, or damage to brain blood vessels, can occur following several conditions including traumatic brain injury or stroke. Dr. McGavern, along with Larry Latour, M.D., NINDS scientist, and their colleagues, observed that a subset of stroke patients developed bleeding and swelling in the brain after surgical removal of the blood vessel clot responsible for the stroke. The swelling, also known as edema, results in poor outcomes and can even be fatal as brain structures become compressed and further damaged.

To understand how vessel injury can lead to swelling and to identify potential treatment strategies, Dr. McGavern and his team developed an animal model of cerebrovascular injury and used state-of-the-art microscopic imaging to watch how the brain responded to the damage in real-time.

Immediately after injury, brain immune cells known as microglia quickly mobilize to stop blood vessels from leaking. These "first responders" of the immune system extend out and wrap their arms around broken blood vessels. Dr. McGavern's group discovered that removing microglia causes irreparable bleeding and damage in the brain.

A few hours later, the damaged brain is invaded by circulating peripheral monocytes and neutrophils (or, myelomonocytic cells). As myelomonocytic cells move from the blood into the brain, they each open a small hole in the vasculature, causing a mist of fluid to enter the brain. When thousands of these cells rush into the brain simultaneously, a lot of fluid comes in all at once and results in swelling.

"The myelomonocytic cells at this stage of repair mean well, and do want to help, but they enter the brain with too much enthusiasm. This can lead to devastating tissue damage and swelling, especially if it occurs around the brain stem, which controls vital functions such as breathing," said Dr. McGavern.

After this initial surge, the monocytic subset of immune cells enter the brain at a slower, less damaging rate and get to work repairing the vessels. Monocytes work together with repair-associated microglia to rebuild the damaged vascular network, which is reconnected within 10 days of injury. The monocytes are required for this important repair process.

In the next set of experiments, Dr. McGavern and his colleagues tried to reduce secondary swelling and tissue damage by using a combination of therapeutic antibodies that stop myelomonocytic cells from entering the brain. The antibodies blocked two different adhesion molecules that myelomonocytic cells use to attach to inflamed blood vessels. These were effective at reducing brain swelling and improving outcomes when administered within six hours of injury.

Interestingly, the therapeutic antibodies did not work if given after six hours or if they were given for too long. In fact, treating mice over a series of days with these antibodies inhibited the proper repair of damaged blood vessels, leading to neuronal death and brain scarring.

"Timing is of the essence when trying to prevent fatal edema. You want to prevent the acute brain swelling and damage, but you do not want to block the monocytes from their beneficial repair work," said Dr. McGavern.

Plans are currently underway for clinical trials to see if administering treatments at specific timepoints will reduce edema and brain damage in a subset of stroke patients. Future research studies will examine additional aspects of the cerebrovascular repair process, with the hope of identifying other therapeutic interventions to promote reparative immune functions.

INFORMATION:

This study was supported by the NINDS Intramural Research Program.

Reference:

Mastorakos P. et al. Temporally Distinct Myeloid Cell Reponses Mediate Damage and Repair After Cerebrovascular Injury. Nature Neuroscience. January 18 2021.

For more information, please visit:

ninds.nih.gov

https://dir.ninds.nih.gov/

The NINDS is the nation's leading funder of research on the brain and nervous system. The mission of NINDS is to seek fundamental knowledge about the brain and nervous system and to use that knowledge to reduce the burden of neurological disease.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

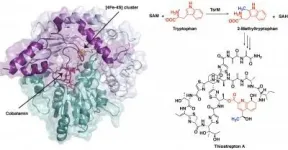

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Images of a protein involved in creating a potent antibiotic reveal the unusual first steps of the antibiotic's synthesis. The improved understanding of the chemistry behind this process, detailed in a new study led by Penn State chemists, could allow researchers to adapt this and similar compounds for use in human medicine.

"The antibiotic thiostrepton is very potent against Gram-positive pathogens and can even target certain breast cancer cells in culture," said Squire Booker, a biochemist at Penn State and investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. "While it has been used ...

HOUSTON — In an effort to address a major challenge when analyzing large single-cell RNA-sequencing datasets, researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have developed a new computational technique to accurately differentiate between data from cancer cells and the variety of normal cells found within tumor samples. The work was published today in Nature Biotechnology.

The new tool, dubbed CopyKAT (copy number karyotyping of aneuploid tumors), allows researchers to more easily examine the complex data obtained from large single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments, which deliver gene expression data from ...

Mount Sinai researchers have published one of the first studies using a machine learning technique called "federated learning" to examine electronic health records to better predict how COVID-19 patients will progress. The study was published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research - Medical Informatics on January 18.

The researchers said the emerging technique holds promise to create more robust machine learning models that extend beyond a single health system without compromising patient privacy. These models, in turn, can help triage patients and improve the quality of their care.

Federated ...

A research team from the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) has developed a process for the electrolytic treatment of wastewater that degrades microplastics at the source. The results of this research have been published in the Environmental Pollution journal.

Wastewater can carry high concentrations of microplastics into the environment. These small particles of less than 5 mm can come from our clothes, usually as microfibers. Professor Patrick Drogui, who led the study, points out there are currently no established degradation methods to handle this contaminant during wastewater ...

Philadelphia, January 18, 2021 - A new study comparing the incidence of sudden deaths occurring outside the hospital across New York City's highly diverse neighborhoods with the percentage of positive SARS-CoV-19 tests found that increased sudden deaths during the pandemic correlate to the extent of virus infection in a neighborhood. The analysis appears in Heart Rhythm, the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, the Cardiac Electrophysiology Society, and the Pediatric & Congenital Electrophysiology Society, published by Elsevier.

"Our research shows the highly diverse regional distribution of out-of-hospital sudden death during ...

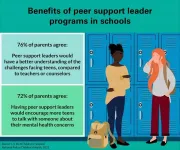

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- An estimated one in five teenagers has symptoms of a mental health disorder such as depression or anxiety, and suicide is the second leading cause of death among teens.

But the first person a teen confides in may not always be an adult - they may prefer to talk to another teen.

And three-quarters of parents in a new national poll think peers better understand teen challenges, compared to teachers or counselors in the school. The majority also agree that peer support leaders at school would encourage more teens to talk with someone about their mental health problems, according to the C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health at Michigan Medicine.

"Peers may provide valuable support for ...

New research examining more than 800,000 traffic stops in Vermont over the course of five years substantiates the term "driving while Black and Brown."

Compared to white drivers, Black and Latinx drivers in Vermont are more likely to be stopped, ticketed, arrested, and searched. But they are less likely to be found with contraband than white drivers. The report finds evidence not only of racial disparities but also racial bias in policing. What's more, a number of these gaps widened over the years examined in the report. With such comprehensive data encompassing the state of Vermont, the authors also found that Vermont police stop cars at a rate ...

A student infected with COVID-19 returning home from university for Christmas would, on average, have infected just less than one other household member with the virus, according to a new model devised by mathematicians at Cardiff University and published in END ...

Variation in consumption of market-acquired foods outside of the traditional diet -- but not in total calories burned daily -- is reliably related to indigenous Amazonian children's body fat, according to a Baylor University study that offers insight into the global obesity epidemic.

"The importance of a poor diet versus low energy expenditure on the development of childhood obesity remains unclear," said Samuel Urlacher, Ph.D., assistant professor of anthropology at Baylor University, CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholar and lead author of the study. "Using gold-standard measures of energy expenditure, we show that relatively lean, rural forager-horticulturalist children in the Amazon spend approximately the same total number of calories each day as their much ...

Spiritualist mediums might be more prone to immersive mental activities and unusual auditory experiences early in life, according to new research.

This might explain why some people and not others eventually adopt spiritualist beliefs and engage in the practice of 'hearing the dead', the study led by Durham University found.

Mediums who "hear" spirits are said to be experiencing clairaudient communications, rather than clairvoyant ("seeing") or clairsentient ("feeling" or "sensing") communications.

The researchers conducted a survey of 65 clairaudient spiritualist mediums from the Spiritualists' National Union and 143 members of the general population in the ...