European eels - one gene pool fits all

2021-01-21

(Press-News.org) European eels spawn in the subtropical Sargasso Sea but spend most of their adult life in a range of fresh- and brackish waters, across Europe and Northern Africa. How eels adapt to such diverse environments has long puzzled biologists. Using whole-genome analysis, a team of scientists led from Uppsala University provides conclusive evidence that all European eels belong to a single panmictic population irrespective of where they spend their adult life, an extraordinary finding for a species living under such variable environmental conditions. The study is published in PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

How species adapt to the environment is of fundamental importance in biology. Genetic changes that facilitate survival in individuals occupying new or variable environments provides the foundation for evolutionary change. These changes can be revealed as differences in the frequency of gene variants between subgroups within species. Alternatively, individuals may respond to changing environments through physiological change without genetic change, a process known as phenotypic plasticity. For example, eels adjust their osmoregulation when migrating from marine waters to freshwater.

"Eels have a truly fascinating life history and go through several stages of metamorphosis", explains Dr. Håkan Wickström, from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and one of the co-authors. "Spawning takes place in the Sargasso Sea, then offspring drift as leptocephali larvae until they reach the European or African continent where they metamorphose into glass eels. Glass eels become yellow eels after entering into brackish or freshwater and later develop into reproductively mature silver eels before returning to the Sargasso Sea for spawning, completing a second crossing of the Atlantic. After that they all die."

"To the best of our knowledge all eels spawn in the Sargasso Sea, but that did not exclude the possible existence of subpopulations", explains Dr. Mats Pettersson, Uppsala University, one of the shared first authors. "For instance, northern eels may spawn in a different region, or at a different depth, or during a different period than southern eels, or they may simply have the ability to recognise conspecifics from the same climatic region. In this study, we wanted to provide the ultimate answer to the important question whether European eels belong to a single panmictic population or not. We have done that after sequencing the entire genomes of eels collected across Europe and North Africa."

"When comparing the DNA sequences of eels from different parts of Europe and North-Africa we do not find any significant differences in the frequency of gene variants", states Mats Pettersson. "We therefore conclude that European eels belong to a single panmictic population and that their ability to inhabit such a wide range of environments must be due to phenotypic plasticity."

"Eels are an enigmatic species that have long captured the imagination of society. Modern genomic analysis allows us to track the evolutionary history of eels, and it is rather impressive that adult eels can inhabit such a range of environments without becoming isolated into genetic subpopulations. It is amazing to think that even with millions of genetic variants we cannot distinguish an eel in a lake in Sweden from an eel in a North-African river. This provides just another clue in a long history of uncovering the life history of this fascinating species", said Dr. Erik Enbody, Uppsala University, and shared first author. "An important implication of these findings is that preventing eel population declines requires international cooperation, as this species constitutes a single breeding population".

In many other marine fish species, subpopulations living in different environments undergo genetic changes associated with local adaptation to that environment. Recent research from the same group in December on the Atlantic herring revealed extensive local adaptation related to, for instance, salinity and water temperature at spawning. European eels are exposed to a much broader range of environmental conditions than the Atlantic herring, but do not have the associated genetic changes. How is this lack of genetic adaptation in eels possible?

"Our hypothesis is that this striking difference between Atlantic herring and Europeans eels is explained by the fact that all eels are spawning under near identical conditions in the Sargasso Sea. Atlantic herring, on the other hand, are spawning in different geographic areas under diverse environmental conditions, with regard to salinity, temperature and season. These conditions require local genetic adaptations because fertilization and early larval development is the most sensitive period during the life of a fish", explains Professor Leif Andersson, Uppsala University and Texas A&M University, who led the study.

"An important topic for future studies is to explore how eels are able to cope with such diverse environmental conditions. It is likely that eels for millions of years have had a life history where spawning takes place under very similar conditions whereas most part of the lifecycle takes place under diverse environmental conditions. Mechanisms for handling this challenge may thus have evolved by natural selection", Leif Andersson ends.

INFORMATION:

Erik D. Enbody et al. (2021) Ecological adaptation in European eels is based on phenotypic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2022620118

Further information, please contact:

Professor Leif Andersson, Professor at Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology at Uppsala University; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Texas A&M University,

Tel: +46 18-471 49 04, cellphone +46 70 425 0233,

email: leif.andersson@imbim.uu.se

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-21

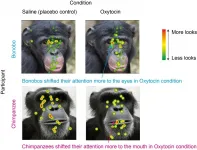

Japan -- Despite being our two closest relatives -- separated by just two million years of evolution from one another and six million from us -- chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans have numerous important differences, such as in lethal aggression demonstrated by chimpanzee males and the high social status of bonobo females.

Now a research study suggests that the hormone oxytocin may have played a central role in this evolutionary divergence.

"Oxytocin is a hormone neuropeptide found in mammals," explains author James Brooks, "but despite its ancient origins, its role can vary even among closely-related species." Among these roles are a wide array of social behaviors, some of which have recently been associated with certain species-typical behaviors in great apes.

Based on these behavioral ...

2021-01-21

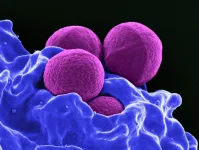

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) ranks among the globally most important causes of infections in humans and is considered a dreaded hospital pathogen. Active and passive immunisation against multi-resistant strains is seen as a potentially valuable alternative to antibiotic therapy. However, all vaccine candidates so far have been clinically unsuccessful. With an epitope-based immunisation, scientists at Cologne University Hospital and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) have now described a new vaccination strategy against S. aureus in the Nature Partner Journal NPJ VACCINES.

S. aureus causes life-threatening conditions such as deep wound infections, sepsis, endocarditis, ...

2021-01-21

PITTSBURGH--A smile that lifts the cheeks and crinkles the eyes is thought by many to be truly genuine. But new research at Carnegie Mellon University casts doubt on whether this joyful facial expression necessarily tells others how a person really feels inside.

In fact, these "smiling eye" smiles, called Duchenne smiles, seem to be related to smile intensity, rather than acting as an indicator of whether a person is happy or not, said Jeffrey Girard, a former post-doctoral researcher at CMU's Language Technologies Institute.

"I do think it's possible that we might ...

2021-01-21

An international research team has developed a fast and affordable quantum random number generator. The device created by scientists from NUST MISIS, Russian Quantum Center, University of Oxford, Goldsmiths, University of London and Freie Universität Berlin produces randomness at a rate of 8.05 gigabits per second, which makes it the fastest random number generator of its kind. The study published in Physical Review X is a promising starting point for the development of commercial random number generators for cryptography and complex systems modeling.

INFORMATION: ...

2021-01-21

ATHENS, Ohio (Jan. 20, 2021) - While the world awaits broad distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, researchers at Ohio University just published highly significant and timely results in the search for another way to stop the virus -- by disrupting its RNA and its ability to reproduce.

Dr. Jennifer Hines, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, along with graduate and undergraduate students in her lab, published the first structural biology analysis of a section of the COVID-19 viral RNA called the stem-loop II motif. This is a non-coding section of the RNA, which means that it is not translated into a protein, but it is likely key to the ...

2021-01-21

LEXINGTON, Ky. (January 20, 2021) - More than 5.7 million Americans live with Alzheimer's disease and that number is projected to triple by 2050. Despite the growing number there is not a cure. Florin Despa a professor with the University of Kentucky's department of pharmacology and nutritional sciences says, "The mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases are largely unknown and effective therapies are lacking." That is why numerous studies and trials are ongoing around the world including at the University of Kentucky. One of those studies by University of Kentucky researchers was recently published in Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. It is the ...

2021-01-21

Older adults are managing the stress of the coronavirus pandemic better than younger adults, reporting less depression and anxiety despite also experiencing greater general concern about COVID-19, according to a study recently published by researchers at the UConn School of Nursing.

Their somewhat paradoxical findings, published last month in the journal Aging and Mental Health, suggest that although greater psychological distress has been reported during the pandemic, older age may offer a buffer against negative feelings brought on by the virus's impact.

"When you think about older adulthood, oftentimes, there are downsides. For example, with regard to physical well-being, we don't recover as well from injury or ...

2021-01-21

Not long after the sun goes down, pairs of burying beetles, or Nicrophorus orbicollis, begin looking for corpses.

For these beetles, this is not some macabre activity; it's house-hunting, and they are in search of the perfect corpse to start a family in. They can sense a good find from miles away, because carrion serves as a food source for countless members of nature's clean-up crew. But because these beetles want to live in these corpses, they don't want to share their discovery. As a result, burying beetles have clever ways of claiming their decaying prize all for themselves. In new research published in The American Naturalist, researchers from UConn and The University of Bayreuth have found these beetles recruit microbes to help throw rivals off the scent.

Immediately following ...

2021-01-21

The NFL playoffs are underway, and fans are finding ways to simulate tailgating during the COVID-19 pandemic. Football watch parties are synonymous with eating fatty foods and drinking alcohol. Have you ever wondered what all of that eating and drinking does to your body?

Researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine simulated a tailgating situation with a small group of overweight but healthy men and examined the impact of the eating and drinking on their livers using blood tests and a liver scan. They discovered remarkably differing responses in the subjects.

"Surprisingly, we found that in overweight men, after an afternoon of eating and drinking, how their bodies reacted to food and drink was not uniform," said Elizabeth Parks, PhD, professor of nutrition and ...

2021-01-21

University of Arizona researchers read between the lines of tree rings to reconstruct exactly what happened in Alaska the year that the Laki Volcano erupted half a world away in Iceland. What they learned can help fine-tune future climate predictions.

In June 1783, Laki spewed more sulfur into the atmosphere than any other Northern Hemisphere eruption in the last 1,000 years. The Inuit in North America tell stories about the year that summer never arrived. Benjamin Franklin, who was in France at the time, noted the "fog" that descended over much of Europe in the aftermath, and correctly reasoned that it led to an unusually cold winter on the continent.

Previous analyses of annual tree rings have shown that the entire 1783 growing season for the spruce ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] European eels - one gene pool fits all