Neuronal recycling: This is how our brain allows us to read

There is no area in the brain that evolved specifically to subserve reading. However, behind this incredibly sophisticated task, there is a more general and evolutionarily remote mechanism.

2021-01-21

(Press-News.org) Letters, syllables, words and sentences--spatially arranged sets of symbols that acquire meaning when we read them. But is there an area and cognitive mechanism in our brain that is specifically devoted to reading? Probably not; written language is too much of a recent invention for the brain to have developed structures specifically dedicated to it.

According to this novel paper published in Current Biology, underlying reading there is evolutionarily ancient function that is more generally used to process many other visual stimuli. To prove it, SISSA researchers subjected volunteers to a series of experiments in which they were shown different symbols and images. Some were very similar to words, others were very much unlike reading material, like nonsensical three-dimensional tripods, or entirely abstract visual gratings; the results showed no difference between the way participants learned to recognise novel stimuli across these three domains. According to the scholars, these data suggest that we process letters and words similarly to how to process any visual stimulus to navigate the world through our visual experiences: we recognise the basic features of a stimulus - shape, size, structure and, yes, even letters and words - and we capture their statistics: how many times they occur, how often they present themselves together, how well one predicts the presence of the other. Thanks to this system, based on the statistical frequency of specific symbols (or combinations thereof), we can recognise orthography, understand it and therefore immerse ourselves in the pleasure of reading.

Reading is a cultural invention, not an evolutionary acquisition

"Written language was invented about 5000 years ago, there was no enough time in evolutionary terms to develop an ad hoc system", explain Yamil Vidal and Davide Crepaldi, lead author and coordinator of the research, respectively, which was also carried out by Eva Viviani, a PhD graduate from SISSA and now post-doc at the university of Oxford, and Davide Zoccolan, coordinator of the Visual Neuroscience Lab, at SISSA, too.

"And yet, a part of our cortex would appear to be specialised in reading in adults: when we have a text in front of us, a specific part of the cortex, the left fusiform gyrus, is activated to carry out this specific task. This same area is implicated in the visual recognition of objects, and faces in particular". On the other hand, explain the scientists, "there are animals such as baboons that can learn to visually recognise words, which suggests that behind this process there is a processing system that is not specific for language, and that get "recycled" for reading as we humans become literate".

Pseudocharacters, 3D objects and abstract shapes to prove the theory

How to shed light on this question? "We started from an assumption: if this theory is true, some effects that occur when we are confronted with orthographic signs should also be found when we are subjected to non-orthographic stimuli. And this is exactly what this study shows". In the research, volunteers were subjected to four different tests. In the first two, they were shown short "words" composed of few pseudocharacters, similar to numbers or letters, but with no real meaning. The scholars explain that this was done to prevent the participants, all adults, from being influenced in their performance by their prior knowledge. "We found that the participants learned to recognise groups of letters - words, in this invented language -- on the basis of the frequency of co-occurrence between their parts: words that were made up of more frequent pairs of pseudocharacters were identified more easily". In the third experiment, they were shown 3D objects that were characterised by triplet of terminal shapes--very much like the invented words were characterised by triplets of letters. In experiment 4, the images were even more abstract and dissimilar from letters. In all the experiments, the response was the same, giving full support to their theory.

From human beings to artificial intelligence: the unsupervised learning

"What emerged from this investigation", explain the authors, "not only supports our hypothesis but also tells us something more about the way we learn. It suggests that a fundamental part of it is the appreciation of statistical regularities in the visual stimuli that surround us". We observe what is around us and, without any awareness, we decompose it into elements and see their statistics; by so doing, we give everything an identity. In jargon, we call it "unsupervised learning". The more often these elements compose themselves in a precise organisation, the better we will be at giving that structure a meaning, be it a group of letters or an animal, a plant or an object. And this, say the scientists, occurs not only in children, but also in adults. "There is, in short, an adaptive development to stimuli which regularly occur. And this is important not only to understand how our brain functions, but also to enhance artificial intelligence systems that base their "learning" on these same statistical principles".

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-21

Research led by the universities of Kent and Oxford has found that fans of the least successful Premier League football teams have a stronger bond with fellow fans and are more 'fused' with their club than supporters of the most successful teams.

The study, which was carried out in 2014, found that fans of Crystal Palace, Hull, Norwich, Sunderland, and West Bromwich Albion were found to have higher loyalty towards one another and even expressed greater willingness to sacrifice their own lives to save the lives of other fans of their club. This willingness was much higher than that of Manchester United, Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool or Manchester City fans. A decade of club statistics from 2003-2013 was used to identify the ...

2021-01-21

Schools are closing again in response to surging levels of COVID-19 infection, but staging randomised trials when students eventually return could help to clarify uncertainties around when we should send children back to the classroom, according to a new study.

Experts say that school reopening policies currently lack a rigorous evidence base - leading to wide variation in policies around the world, but staging cluster randomized trials (CRT) would create a body of evidence to help policy makers take the right decisions.

The pandemic's rapid ...

2021-01-21

Despite being the subject of increasing interest for a whole century, how preeclampsia develops has been unclear - until now.

Researchers believe that they have now found a primary cause of preeclampsia.

"We've found a missing piece to the puzzle. Cholesterol crystals are the key and we're the first to bring this to light," says researcher Gabriela Silva.

Silva works at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) Centre of Molecular Inflammation Research (CEMIR), a Centre of Excellence, where she is part of a research group for inflammation in pregnancy led by Professor Ann-Charlotte Iversen.

The findings are good news for the approximately three per cent of pregnant ...

2021-01-21

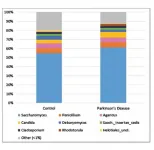

Amsterdam, NL, January 21, 2021 - The bacterial gut microbiome is strongly associated with Parkinson's disease (PD), but no studies had previously investigated he role of fungi in the gut. In this novel study published in the Journal of Parkinson's Disease, a team of investigators at the University of British Columbia examined whether the fungal constituents of the gut microbiome are associated with PD. Their research indicated that gut fungi are not a contributing factor, thereby refuting the need for any potential anti-fungal treatments of the gut in PD patients.

"Several studies conducted since 2014 have characterized changes in the gut microbiome," explained lead investigator Silke Appel-Cresswell, MD, Pacific Parkinson's Research Centre and Djavad ...

2021-01-21

The cause of the inflammatory lung disease sarcoidosis is unknown. In a new study, researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have investigated whether a type of immune cell called a monocyte could be a key player in sarcoidosis pathogenesis and explain why some patients develop more severe and chronic disease than others. The study, which is published in The European Respiratory Journal, opens new possibilities for future diagnostic and therapeutic methods.

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease that in 90 percent of cases affects the lungs, but can also attack the heart, skin and lymph system. The cause of the disease is not yet established, and there is currently ...

2021-01-21

Scientists have developed a pioneering new technique that could revolutionise the accuracy, precision and clarity of super-resolution imaging systems.

A team of scientists, led by Dr Christian Soeller from the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, which champions interdisciplinary research and is a hub for new high-resolution measurement techniques, has developed a new way to improve the very fine, molecular imaging of biological samples.

The new method builds upon the success of an existing super-resolution imaging technique called DNA-PAINT ...

2021-01-21

Scientists have been pondering if the microbiome of plants is due to nature or nurture. Research at Stockholm University, published in Environmental Microbiology, showed that oak acorns contain a large diversity of microbes, and that oak seedlings inherit their microbiome from these acorns.

"The idea that seeds can be the link between the microbes in the mother tree and its offspring has frequently been discussed, but this is the first time someone proves the transmission route from the seed to the leaves and roots of emerging plants", says Ahmed Abdelfattah, researcher at the Department of Ecology Environment and Plant ...

2021-01-21

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- In 2018, passengers onboard a flight to Australia experienced a terrifying 10-second nosedive when a vortex trailing their plane crossed into the wake of another flight. The collision of these vortices, the airline suspected, created violent turbulence that led to a free fall.

To help design aircraft that can better maneuver in extreme situations, Purdue University researchers have developed a modeling approach that simulates the entire process of a vortex collision at a reduced computational time. This physics knowledge could then be incorporated into engineering design codes so that the aircraft ...

2021-01-21

(Boston)--While aging is an unavoidable biological process with many influencing factors that results in visible changes to the hair, there is limited literature examining the characteristics of hair aging across the races. Now a new study describes the unique characteristics of hair aging among different ethnicities that the authors hope will aid in a culturally sensitive approach when making recommendations to prevent hair damage during one's life-time.

Among the findings: hair-graying onset varies with race, with the average age for Caucasians being mid-30s, that for Asians being late 30s, and ...

2021-01-21

LAWRENCE -- The COVID-19 pandemic has created new perils and challenges for people experiencing substance use disorders and addictive behaviors. Social distancing and isolation can trigger loneliness, anxiety and depression. These circumstances have put some "recreational users" at risk for developing addictions and caused some in recovery from addictions to relapse.

At the same time, the pandemic has made it nearly impossible for mutual-help (e.g., AA, NA) recovery groups to gather in person, forcing a scramble to provide remote support through platforms like Zoom.

Now, researchers at the Cofrin Logan Center for Addiction Research and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Neuronal recycling: This is how our brain allows us to read

There is no area in the brain that evolved specifically to subserve reading. However, behind this incredibly sophisticated task, there is a more general and evolutionarily remote mechanism.