(Press-News.org) Systems for capturing and converting carbon dioxide from power plant emissions could be important tools for curbing climate change, but most are relatively inefficient and expensive. Now, researchers at MIT have developed a method that could significantly boost the performance of systems that use catalytic surfaces to enhance the rates of carbon-sequestering electrochemical reactions.

Such catalytic systems are an attractive option for carbon capture because they can produce useful, valuable products, such as transportation fuels or chemical feedstocks. This output can help to subsidize the process, offsetting the costs of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

In these systems, typically a stream of gas containing carbon dioxide passes through water to deliver carbon dioxide for the electrochemical reaction. The movement through water is sluggish, which slows the rate of conversion of the carbon dioxide. The new design ensures that the carbon dioxide stream stays concentrated in the water right next to the catalyst surface. This concentration, the researchers have shown, can nearly double the performance of the system.

The results are described today in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science in a paper by MIT postdoc Sami Khan PhD '19, who is now an assistant professor at Simon Fraser University, along with MIT professors of mechanical engineering Kripa Varanasi and Yang Shao-Horn, and recent graduate Jonathan Hwang PhD '19.

"Carbon dioxide sequestration is the challenge of our times," Varanasi says. There are a number of approaches, including geological sequestration, ocean storage, mineralization, and chemical conversion. When it comes to making useful, saleable products out of this greenhouse gas, electrochemical conversion is particularly promising, but it still needs improvements to become economically viable. "The goal of our work was to understand what's the big bottleneck in this process, and to improve or mitigate that bottleneck," he says.

The bottleneck turned out to involve the delivery of the carbon dioxide to the catalytic surface that promotes the desired chemical transformations, the researchers found. In these electrochemical systems, the stream of carbon dioxide-containing gases is mixed with water, either under pressure or by bubbling it through a container outfitted with electrodes of a catalyst material such as copper. A voltage is then applied to promote chemical reactions producing carbon compounds that can be transformed into fuels or other products.

There are two challenges in such systems: The reaction can proceed so fast that it uses up the supply of carbon dioxide reaching the catalyst more quickly than it can be replenished; and if that happens, a competing reaction -- the splitting of water into hydrogen and oxygen -- can take over and sap much of the energy being put into the reaction.

Previous efforts to optimize these reactions by texturing the catalyst surfaces to increase the surface area for reactions had failed to deliver on their expectations, because the carbon dioxide supply to the surface couldn't keep up with the increased reaction rate, thereby switching to hydrogen production over time.

The researchers addressed these problems through the use of a gas-attracting surface placed in close proximity to the catalyst material. This material is a specially textured "gasphilic," superhydrophobic material that repels water but allows a smooth layer of gas called a plastron to stay close along its surface. It keeps the incoming flow of carbon dioxide right up against the catalyst so that the desired carbon dioxide conversion reactions can be maximized. By using dye-based pH indicators, the researchers were able to visualize carbon dioxide concentration gradients in the test cell and show that the enhanced concentration of carbon dioxide emanates from the plastron.

In a series of lab experiments using this setup, the rate of the carbon conversion reaction nearly doubled. It was also sustained over time, whereas in previous experiments the reaction quickly faded out. The system produced high rates of ethylene, propanol, and ethanol -- a potential automotive fuel. Meanwhile, the competing hydrogen evolution was sharply curtailed. Although the new work makes it possible to fine-tune the system to produce the desired mix of product, in some applications, optimizing for hydrogen production as a fuel might be the desired result, which can also be done.

"The important metric is selectivity," Khan says, referring to the ability to generate valuable compounds that will be produced by a given mix of materials, textures, and voltages, and to adjust the configuration according to the desired output.

By concentrating the carbon dioxide next to the catalyst surface, the new system also produced two new potentially useful carbon compounds, acetone, and acetate, that had not previously been detected in any such electrochemical systems at appreciable rates.

In this initial laboratory work, a single strip of the hydrophobic, gas-attracting material was placed next to a single copper electrode, but in future work a practical device might be made using a dense set of interleaved pairs of plates, Varanasi suggests.

Compared to previous work on electrochemical carbon reduction with nanostructure catalysts, Varanasi says, "we significantly outperform them all, because even though it's the same catalyst, it's how we are delivering the carbon dioxide that changes the game."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the Italian energy firm Eni S.p.A through the MIT Energy Initiative, and a NSERC PGS-D postgraduate scholarship from Canada.

Written by David L. Chandler, MIT News Office

Additional background

Paper: "Catalyst-Proximal Plastrons Enhance Activity and Selectivity of Carbon Dioxide Electroreduction."

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports-physical-science/fulltext/S2666-3864(20)30348-9

For many years, clinicians have been hesitant to diagnose adolescents with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), believing it was a mental health "death sentence" for a patient because there was no clear treatment. Carla Sharp, professor of psychology and director of the Developmental Psychopathology Lab at the University of Houston, begs to differ.

And her new research, published in Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology backs her up.

"Like adult BPD, adolescent BPD appears to be not as intractable and treatment resistant as previously thought," reports Sharp. "That means we should not shy away from identifying BPD in adolescents and we shouldn't ...

Halogen atoms (Cl and Br) strongly influence the atmospheric chemical composition. Since 1970s, scientists discovered that these atoms were responsible for depletion of ozone in the stratosphere and ground-level ozone of the Arctic. In the past decade, there is emerging recognition that halogen atoms also play important roles in tropospheric chemistry and air quality. However, the knowledge of halogen atoms in continental regions is still incomplete.

"In the troposphere, halogen atoms can kick start hydrocarbon oxidation that makes ozone, modify the oxidative capacity, perturb ...

A survey of dog owners from across the U.S. shows that when it comes to seeking veterinary care for dogs, barriers to access - including a lack of trust - have more effect on the decision-making process than differences in race, gender or socioeconomic status. The results could aid veterinarians in developing outreach strategies for underserved communities.

"I was interested in how different demographic groups viewed health care and how those views might affect relationships between veterinarians and their clients," says Rachel Park, a Ph.D. student at North Carolina State University and first author of a paper describing the work. "The existing literature wasn't national in scope and hadn't accounted for multiple identities held, such as one's socioeconomic status or ...

In the past 20 years, humans have suffered several serious epidemics from emerging viruses, such as SARS, swine flu, Ebola, MERS and (most recently) SARS-CoV-2. During each epidemic, an accurate, rapid, and accessible molecular diagnostic test is highly essential for the control and prevention of viral diseases. In particular, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is spreading rapidly in most countries, resulting in a severe global pandemic, which has a profound impact on the world economy and people's normal life. Accurate and rapid diagnosis of COVID-19 has been the most crucial measure for controlling the ...

FINDINGS

A study led by researchers at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center found shortening a traditional 45-day course of radiation to a five-day course delivered in larger doses is safe and as effective as conventional radiation for men with high-risk forms of prostate cancer.

The findings show the five-day regimen of stereotactic body radiotherapy, a form of external beam radiation therapy that uses a higher dose of radiation, had a four-year cure rate of 82%. Severe side effects were also rare. Around 2% experienced urinary issues and less than 1% had bowel side effects.

BACKGROUND

Building on previous UCLA research that provided significant evidence that a shortened regimen of radiation could be ...

(Boston)--Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with a higher risk of complications including ischemic stroke, cognitive decline, heart failure, myocardial infarction and death. AF frequently is undetected until complications such as stroke or heart failure occur.

While the public and clinicians have an intense interest in detecting AF earlier, the most appropriate strategies to detect undiagnosed AF and medical prognosis and therapeutic implications of AF detected by screening are uncertain.

A new report led by Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) researcher Emelia J. Benjamin, MD, ScM, builds upon a recently conducted National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's virtual workshop that focused on identifying key research priorities related to AF screening.

Global experts reviewed ...

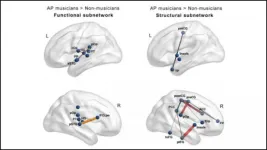

The brains of musicians have stronger structural and functional connections compared to those of non-musicians, regardless of innate pitch ability, according to new research from JNeurosci.

Years of musical training shape the brain in dramatic ways. A minority of musicians -- with Mozart and Michael Jackson in their ranks -- also possess absolute pitch, the ability to identify a tone without a reference. But, it remains unclear how this ability impacts the brain.

In the biggest sample to date, Leipold et al. compared the brains of professional musicians, some with absolute pitch and some without, to non-musicians. To the team's surprise, there were no strong differences ...

An extensive review of cephalopod fauna from the Northwest African Atlantic coast was performed by researchers from the University of Vigo (Spain) and the Spanish Institute of Oceanography ( END ...

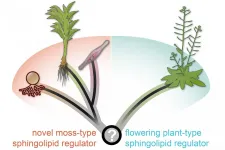

A team led by plant biologists at the Universities of Freiburg and Göttingen in Germany has shown for the first time that mosses have a mechanism to protect them against cold that was previously known only in flowering plants. Professor Ralf Reski at the Cluster of Excellence Centre for Integrative Biological Signalling Studies (CIBSS) at the University of Freiburg and Professor Ivo Feussner at the Center for Molecular Biosciences (GZMB) at the University of Göttingen have also demonstrated that this mechanism has an evolutionarily independent origin - mosses and flowering ...

Every living organism has DNA, and every living organism engages in DNA replication, the process by which DNA makes an exact copy of itself during cell division. While it's a tried-and-true process, problems can arise.

Break-induced replication (BIR) is a way to solve those problems. In humans, it is employed chiefly to repair breaks in DNA that cannot be fixed otherwise. Yet BIR itself, through its repairs to DNA and how it conducts those repairs, can introduce or cause genomic rearrangements and mutations contributing to cancer development.

"It's kind of a double-edged sword," says Anna Malkova, professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Iowa, who has studied ...