New study: Malaria tricks the brain's defence system

2021-01-26

(Press-News.org) Every year, more than 400,000 people die from malaria, the majority are children under the age of five years old, who die from a disease which affects more than 200 million people a year.

The most serious form of the disease is cerebral malaria which may cause severe neurological consequences and, in the worst-case scenario, result in death. The precise mechanism behind cerebral malaria has remained a mystery - until now, says a research group from the Department of Immunology and Microbiology at the University of Copenhagen.

'In our study, we show that a certain type of the malaria parasite can cross the blood-brain barrier by utilising a mechanism that is also used by immune cells in special cases. It is a major breakthrough in the understanding of cerebral malaria, and it partly explains the disease process seen in brain infections', says Professor Anja Ramstedt Jensen who, together with her colleague, Assistant Professor Yvonne Adams, has headed the study.

Malaria mimics immune cells

The blood-brain barrier is the guarding barrier between the brain´s blood vessels and the cells and other components that make up brain tissue. The barrier ensures that only certain molecules are allowed to pass through to the brain cells. It prevents harmful substances and microorganisms from crossing, but, in some cases, it allows the white blood cells which are an important part of our immune system to pass through.

'The malaria parasite takes up residence in red blood cells. However, since red blood cells cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, it has so far been our understanding that malaria parasites could not enter into brain tissue. Now we can show that the parasite is able to mimic the mechanism that the immune system's white blood cells use to cross the barrier, and we now know that this helps to explain the disease mechanism behind cerebral malaria', says Anja Ramstedt Jensen.

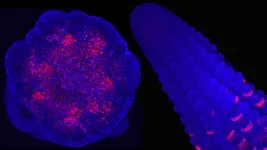

To investigate the mechanism behind cerebral malaria, the researchers have created a 3D model of the blood-brain barrier consisting of, among other things, brain cells which they have grown in cell culture. The method has so far been used in other contexts to study which drugs and peptides can cross the blood-brain barrier. But this is the first time the method has been used to study infections.

'This is completely new knowledge within malaria research. Previously, we have only been able to study how red blood cells with the malaria parasite bind to brain cells, but not whether they can penetrate brain cells', says Assistant Professor Yvonne Adams.

Based on this new method, the researchers are now in the process of further studying the molecular details that explain how malaria parasites penetrate the so-called endothelial cells, which are the cells in the blood-brain barrier that allow or reject access of molecules to our brain tissue.

'In addition, we are expanding our studies and the application of the method to other diseases such as Lyme disease, Borrelia, which is the most common cause of bacterial brain infection in Denmark and, among other things, causes meningitis and other forms of inflammation in the central nervous system', says Anja Ramstedt Jensen.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-26

Mangrove ecosystems are at particular risk of being polluted by plastic carried from rivers to the sea. Fifty-four per cent of mangrove habitat is within 20 km of a river that discharges more than a tonne of plastic waste a year into the ocean, according to a new paper published in the journal Science of the Total Environment. Mangroves in southeast Asia are especially threatened by river-borne plastic pollution, the researchers found.

The paper, written by scientists at GRID-Arendal and the University of Bergen, is the first global assessment of coastal environments' exposure to river-borne plastic pollution. The majority of plastic waste carried to sea by rivers ends up trapped along coastlines, but some types ...

2021-01-26

FORT LAUDERDALE/DAVIE, Fla. - Global warming or climate change. It doesn't matter what you call it. What matters is that right now it is having a direct and dramatic effect on marine environments across our planet.

"More immediately pressing than future climate change is the increasing frequency and severity of extreme 'underwater heatwaves' that we are already seeing around the world today," Lauren Nadler, Ph.D., who is an assistant professor in Nova Southeastern University's (NSU) Halmos College of Arts and Sciences . "This phenomenon is what we wanted to both simulate and understand."

Nadler is a co-author of a new study on this topic, which you can find published online ...

2021-01-26

Scientists have designed a single-dose universal vaccine that could protect against the many forms of leptospirosis bacteria, according to a study published today in eLife.

An effective vaccine would help prevent the life-threatening conditions caused by leptospirosis, such as Weil's disease and lung haemorrhage, which are fatal in 10% and 50% of cases, respectively.

Leptospirosis is caused by a diverse group of spirochetes called leptospires. A broad range of mammals, including rats, harbour the bacteria in their kidneys and release them into the environment through their urine. Humans and animals can then get infected after coming into contact with contaminated water or soil. In addition to having a major impact on the health of vulnerable human populations, ...

2021-01-26

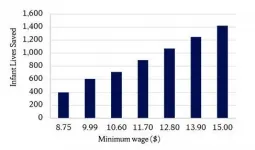

Syracuse, N.Y. - As President Joe Biden seeks to raise the federal minimum wage, a new study published recently by researchers from Syracuse University shows that a higher minimum wage will reduce infant deaths.

In the study, "Effects of US state preemption laws on infant mortality," Syracuse University professors found that each additional dollar of minimum wage reduces infant deaths by up to 1.8 percent annually in large U.S. cities. The study was published recently by Preventive Medicine.

The federal minimum wage has not been increased since 2009, and Biden's $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan to aid those hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic calls for Congress to raise the minimum wage from $7.25 ...

2021-01-26

CAMBRIDGE, MD (January 26, 2021)--The Chesapeake Bay has a long history of nutrient pollution resulting in degraded water quality. However, scientists from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science are reporting some improvements in the Choptank River on Maryland's Eastern Shore.

The Choptank is a tributary of Chesapeake Bay, and its watershed lies primarily in the state of Maryland, with a portion in Delaware. There are strong similarities between the Choptank basin and the Chesapeake as a whole, which enables the Choptank to be used as a model for progress in the Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay is an estuary which has undergone considerable ...

2021-01-26

Researchers from McGill University have discovered, for the first time, one of the possible mechanisms that contributes to the ability of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) to increase social interaction. The findings, which could help unlock potential therapeutic applications in treating certain psychiatric diseases, including anxiety and alcohol use disorders, are published in the journal PNAS.

Psychedelic drugs, including LSD, were popular in the 1970s and have been gaining popularity over the past decade, with reports of young professionals claiming to regularly take small non-hallucinogenic micro-doses of ...

2021-01-26

Black holes are considered amongst the most mysterious objects in the universe. Part of their intrigue arises from the fact that they are actually amongst the simplest solutions to Einstein's field equations of general relativity. In fact, black holes can be fully characterized by only three physical quantities: their mass, spin and charge. Since they have no additional "hairy" attributes to distinguish them, black holes are said to have "no hair": Black holes of the same mass, spin, and charge are exactly identical to each other.

Dr. Lior Burko of Theiss Research in collaboration with Professor Gaurav Khanna of the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and the University ...

2021-01-26

Landslides caused by the collapse of unstable volcanoes are one of the major dangers of volcanic eruptions. A method to detect long-term movements of these mountains using satellite images could help identify previously overlooked instability at some volcanoes, according to Penn State scientists.

"Whenever there is a large volcanic eruption, there is a chance that if a flank of the volcano is unstable there could be a collapse," said Judit Gonzalez-Santana, a doctoral student in the Department of Geosciences. "To better explore this hazard, we applied an increasingly popular and more sensitive time-series method to look at these movements, or surface ...

2021-01-26

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- The Medicaid expansion facilitated by the Affordable Care Act led to increases in the identification of undiagnosed HIV infections and in the use of HIV prevention services such as preexposure prophylaxis drugs, says new research co-written by a team of University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign experts who study the intersection of health care and public policy.

The research by Dolores Albarracín, a professor of psychology and of business administration at Illinois, and Bita Fayaz Farkhad, an economist and a postdoctoral researcher in psychology at Illinois, ...

2021-01-26

Corn hasn't always been the sweet, juicy delight that we know today. And, without adapting to a rapidly changing climate, it is at risk of losing its place as a food staple. Putting together a plant is a genetic puzzle, with hundreds of genes working together as it grows. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor David Jackson worked with Associate Professor Jesse Gillis to study genes involved in corn development. Their teams analyzed thousands of individual cells that make up the developing corn ear. They created the first anatomical map that shows where and when important ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New study: Malaria tricks the brain's defence system