When push comes to shove, what counts as a fight?

Biologists come up with new way to decide whether to lump together similar animal behaviors. It could help all animal behaviorists.

2021-01-26

(Press-News.org) Biologists often study animal sociality by collecting observations about several types of behavioral interactions. These interactions can be things like severe fights, minor fights, cooperative food sharing, or grooming each other.

But to analyze animal behavior, researchers need to make decisions about how to categorize these interactions and how to code these behaviors during data collection. Turns out, this question can be complicated.

Researchers at the University of Cincinnati dug into this tricky question while studying monk parakeets. In new research, published in the journal Current Zoology, the team asked: How do you properly categorize two seemingly similar behaviors? The study was led by UC postdoctoral researcher Annemarie van der Marel who worked with UC PhD students Sanjay Prasher, Claire O'Connell, and Chelsea Carminito and UC Assistant Professor Elizabeth Hobson.

"Biologists have to deal with this question: are the behaviors that we categorize as unique actually perceived as unique by the animals?" Hobson said. "How do the animals classify those behaviors?"

Biases can easily lead researchers astray in making these judgement calls. "If you look at chimpanzees, smiling is an aggressive behavior. But in humans, smiling is friendly," said van der Marel. "The behaviors look similar to us but the nuances of how the behaviors are used are very different."

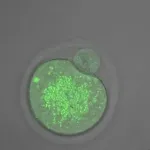

Monk parakeets are highly social parrots that live in large colonies where they often interact with other individuals. The parakeets spend a large proportion of the day fighting, especially top-ranked birds, which makes it easy to distinguish them from birds ranked lower in the dominance hierarchy, said O'Connell. The birds demonstrate aggression in many ways. They bite, of course. But monk parakeets also like to take another parrot's perch through menace or sheer force.

UC biologists observed two types of this "king of the hill" behavior: "displacements", where one bird lunges at another bird and can bite to force that bird away, and "crowding", where a threatened bird moves before an aggressor is within biting range. The team coded these behaviors as distinct because they appeared to differ in the level of aggression, with displacements appearing as a more severe form of aggression with a higher potential for injury.

The parakeets also used these behaviors somewhat differently, with displacements occurring much more often than the crowding.

The question is: were these behaviors essentially used in the same ways by the birds, so that they could be treated as the same types of events in later analyses?

Pooling two behaviors has major research benefits such as creating a richer dataset for future analyses. But pooling also carries a risk -- by generalizing, scientists could be losing nuances of behaviors that convey important information when considered alone, Hobson said.

To get to the bottom of this question, the team turned to computational analysis. They created a new computer model that compared the real aggression patterns to ones that were randomized. This approach allowed the team to test whether treating the two behaviors as interchangeable caused any changes in the social structure. "On top of being a great lab bonding experience, it was an exciting opportunity to learn how to use simulations to help answer research questions" Prasher said.

In the UC study, their computational analysis supported pooling the two behaviors. For the UC team, these results will help them plan their future analyses as they work to understand the complex social lives of these parakeets. More broadly, van der Marel said the new framework can also help other animal-behavior researchers make informed and data-driven decisions about when to pool together behaviors and when to separate them.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-26

University of Alberta researchers have taken another step forward in developing an artificial intelligence tool to predict schizophrenia by analyzing brain scans.

In recently published research, the tool was used to analyze functional magnetic resonance images of 57 healthy first-degree relatives (siblings or children) of schizophrenia patients. It accurately identified the 14 individuals who scored highest on a self-reported schizotypal personality trait scale.

Schizophrenia, which affects 300,000 Canadians, can cause delusions, hallucinations, disorganized ...

2021-01-26

SAN ANTONIO and BOSTON - Study findings released Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) hold both good news and bad news about transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), which are harbingers of subsequent strokes.

Sudha Seshadri, MD, professor of neurology at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and director of the university's Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer's and Neurodegenerative Diseases, is senior author of the study and senior investigator of the Framingham Heart Study, from which the findings are derived. She said the extensive follow-up of Framingham participants over more than six decades enabled the study to present a more-complete picture of the risk of stroke to patients after a TIA.

The study points to the need for ...

2021-01-26

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Research led by The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and College of Medicine identified a new compound that might serve as a basis for developing a new class of drugs for diabetes.

Study findings are published online in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

The adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (Ampk) is a crucial enzyme involved in sensing the body's energy stores in cells. Impaired energy metabolism is seen in obesity, which is a risk factor for diabetes. Some medications used to treat diabetes, such as metformin, work by increasing the activity of Ampk.

"In ...

2021-01-26

African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) is a disease transmitted by tsetse flies and is fatal to humans and other animals; however, there is currently no vaccine, this disease is mainly controlled by reducing insect populations and patient treatment. A study published in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Alvaro Acosta-Serrano at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and an international team of researchers suggests that the approved drug nitisinone could be repurposed to kill tsetse flies without harming important pollinator insects.

Currently, the most effective method of controlling the transmission of African trypanosomiasis is by employing insecticide-based vector control campaigns (traps, targets, ...

2021-01-26

The COHERENT particle physics experiment at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory has firmly established the existence of a new kind of neutrino interaction. Because neutrinos are electrically neutral and interact only weakly with matter, the quest to observe this interaction drove advances in detector technology and has added new information to theories aiming to explain mysteries of the cosmos.

"The neutrino is thought to be at the heart of many open questions about the nature of the universe," said Indiana University physics professor Rex Tayloe. He led the installation, operation and data analysis of a cryogenic liquid argon ...

2021-01-26

A Brazilian study published in the journal Molecular Human Reproduction helps understand why obese mothers tend to have children with a propensity to develop metabolic disease during their lifetime, as suggested by previous research.

According to the authors, "transgenerational transmission of metabolic diseases" may be associated with Mfn2 deficiency in the mother's oocytes (immature eggs). Mfn2 refers to mitofusin-2, a protein involved in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. It is normally found in the outer membrane of mitochondria, ...

2021-01-26

Incidence rates of skin cancer (cutaneous malignant melanoma) have increased more than 550% in males and 250% in females since the early 1980s in England - according to a new study by Brighton and Sussex Medical School (BSMS).

Published in the new Lancet journal, The Lancet Regional Health - Europe, the study analysed data on more than 265,000 individuals diagnosed with skin cancer in England over the 38-year period, 1981-2018.

Skin cancer is the fifth most common cancer in the UK, with about 16,200 new cases each year.

Excessive exposure to UV radiation from the sun (or sunlight) is the main environmental risk factor for developing skin cancer. It is estimated that about 86% of all skin cancers in the UK are ...

2021-01-26

Since the founding of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, member states have regularly agreed on global strategies to bring the increasingly rapid loss of biodiversity to a halt. In 2002, the heads of state adopted the so-called 2010 biodiversity targets. Eight years later, little progress had been made and 20 new, even more ambitious goals were set for the next ten years. Last year, it became clear that this target had been missed, too. The loss of biodiversity continues unabated.

This year, new targets are being negotiated again - this time for 2030. The decisions are to be made at the Conference of the Parties (COP15) in Kunming, China. To ...

2021-01-26

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- The actions that older adults take on Facebook may be more important to their user experience and well-being than their overall use of the site, according to researchers.

In a study conducted by a team that included researchers from Penn State, older adults experienced different levels of competence, relatedness and autonomy on Facebook based on the types of their activities on the site.

Specifically, older adults who posted more pictures to Facebook felt more competent, which led to significantly higher levels of well-being in general, ...

2021-01-26

Researchers from North Carolina State University have created a trifunctional contraceptive gel that contains spermicidal, anti-viral and libido-enhancing agents in one formulation. When tested in a rat model, the gel both enhanced male libido and prevented pregnancy in 100% of cases, as compared to an average 87% effective rate with a commercially available contraceptive gel.

"We are using three pharmacological agents in a new formulation," says Ke Cheng, Randall B. Terry, Jr. Distinguished Professor in Regenerative Medicine at NC State's College of Veterinary Medicine, professor in the NC State/UNC Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering and corresponding author of a paper describing the work. "Our hope ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] When push comes to shove, what counts as a fight?

Biologists come up with new way to decide whether to lump together similar animal behaviors. It could help all animal behaviorists.