(Press-News.org) People with schizophrenia, a mental disorder that affects mood and perception of reality, are almost three times more likely to die from the coronavirus than those without the psychiatric illness, a new study shows. Their higher risk, the investigators say, cannot be explained by other factors that often accompany serious mental health disorders, such as higher rates of heart disease, diabetes, and smoking.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the investigation showed that schizophrenia is by far the biggest risk factor (2.7 times increased odds of dying) after age (being 75 or older increased the odds of dying 35.7 times). Male sex, heart disease, and race ranked next after schizophrenia in order.

"Our findings illustrate that people with schizophrenia are extremely vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19," says study lead author Katlyn Nemani, MD. "With this newfound understanding, health care providers can better prioritize vaccine distribution, testing, and medical care for this group," adds Nemani, a research assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at NYU Langone Health.

The study also showed that people with other mental health problems such as mood or anxiety disorders were not at increased risk of death from coronavirus infection.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, experts have searched for risk factors that make people more likely to succumb to the disease to bolster protective measures and allocate limited resources to people with the greatest need. Although previous studies have linked psychiatric disorders in general to an increased risk of dying from the virus, the relationship between the coronavirus and schizophrenia specifically has remained unclear. A higher risk of mortality was expected among those with schizophrenia, but not at the magnitude the study found, the researchers say.

The new investigation is publishing Jan. 27 in the journal JAMA Psychiatry. Researchers believed that other issues such as heart disease, depression, and barriers in getting care were behind the low life expectancy seen in schizophrenia patients, who on average die 15 years earlier than those without the disorder. The results of the new study, however, suggest that there may be something about the biology of schizophrenia itself that is making those who have it more vulnerable to COVID-19 and other viral infections. One likely explanation is an immune system disturbance, possibly tied to the genetics of the disorder, says Nemani.

For the investigation, the research team analyzed 7,348 patient records of men and women treated for COVID-19 at the height of the pandemic in NYU Langone hospitals in New York City and Long Island between March 3 and May 31, 2020. Of these cases, they identified 14 percent who were diagnosed with schizophrenia, mood disorders, or anxiety. Then, the researchers calculated patient death rates within 45 days of testing positive for the virus.

They note that this large sample of patients who all were infected with the same virus provided a unique opportunity to study the underlying effects of schizophrenia on the body.

"Now that we have a better understanding of the disease, we can more deeply examine what, if any, immune system problems might contribute to the high death rates seen in these patients with schizophrenia," says study senior author Donald Goff, MD. Goff is the Marvin Stern Professor of Psychiatry at NYU Langone.

Goff, also the director of the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research at NYU Langone, says the study investigators plan to explore whether medications used to treat schizophrenia, such as antipsychotic drugs, may play a role as well.

He cautions that the study authors could only determine the risk for patients with schizophrenia who had access to testing and medical care. Further research is needed, he says, to clarify how dangerous the virus may be for those who lack these resources. Goff is also the vice chair for research in the Department of Psychiatry at NYU Langone.

Study funding was provided by NYU Langone.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Nemani and Goff, other NYU Langone researchers included Chenxiang Li, PhD; Esther Blessing, MD; PhD; Narges Razavian, PhD; Ji Chen, MS; and Eva Petkova, PhD. Another study investigator was Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, at Columbia University in New York.

Media Inquiries

Shira Polan

212-404-4279

shira.polan@nyulangone.org

The inner ear of a 400 million-year-old 'platypus fish' has yielded new insights into early vertebrate evolution, suggesting this ancient creature may be more closely related to modern-day sharks and bony fish than previously thought.

A team of scientists from the University of Birmingham in the UK, and institutions in China, Australia and Sweden, used 'virtual anatomy' techniques, including MicroCT scanning (using x-rays to look inside the fossil) and digital reconstruction to examine previously unseen areas within the braincase of these mysterious fossils.

They discovered the fish, called ...

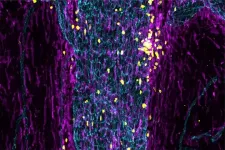

BOSTON -- For the first time, scientists have identified the individual neurons critical to human social reasoning, a cognitive process that requires us to acknowledge and predict others' hidden beliefs and thoughts. A team of neuroscientists at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) had a rare look at how individual neurons represent the beliefs of others by recording neuron activity in patients undergoing neurosurgery to alleviate symptoms of motor disorders such as Parkinson's disease. Their findings are published in Nature.

The researchers were studying a very complex social cognitive ...

What The Study Did: This study among patients in Italy suggests that despite virological recovery, a sizable proportion of patients with COVID-19 experienced respiratory, functional or psychological conditions months after hospital discharge.

Authors: Mattia Bellan, M.D., Ph.D., of Università del Piemonte Orientale in Novara, Italy, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36142)

Editor's ...

What The Study Did: In this observational study of about 7,300 adults with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in a New York health system, a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis was associated with an increased risk of death after adjusting for demographic and medical risk factors. Mood and anxiety disorders weren't associated with increased risk of mortality.

Authors: Donald C. Goff, M.D., of New York University Langone Medical Center in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4442)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the association between the pandemic and clinical research and development by studying the initiation of oncology clinical trials over time.

Authors: Elizabeth B. Lamont, M.D., M.S., M.MSc., of Acorn AI by Medidata, a Dassault Systèmes Company, in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36353)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...

New findings on the brain and inner ear cavity of a 400-million-year-old platypus-like fish cast light on the evolution of modern jawed vertebrates, according to a study led by Dr. ZHU Youan and Dr. LU Jing from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The study was published in Current Biology on Jan 27.

Back in 1960s, Paleontologist Dr. Gavin C. Young found several fossils of a long-beaked fish, a type of placoderm, in the Burrinjuck limestones in Australia. He named the fish Brindabellaspis stensioi, and other people jokingly dubbed it "platypus fish" because of its long ...

Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, autism, schizophrenia and many other neurological and psychiatric conditions have been linked to inflammation in the brain. There's growing evidence that immune cells and molecules play a key role in normal brain development and function as well. But at the core of the burgeoning field of neuroimmunology lies a mystery: How does the immune system even know what's happening in the brain? Generations of students have been taught that the brain is immunoprivileged, meaning the immune system largely steers clear of it.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis believe they have figured out how the immune system keeps tabs on what's going on in the brain. Immune ...

What makes cancer cells different from ordinary cells in our bodies? Can these differences be used to strike at them and paralyze their activity? This basic question has bothered cancer researchers since the mid-19th century. The search for unique characteristics of cancer cells is a building block of modern cancer research. A new study led by researchers from Tel Aviv University shows, for the first time, how an abnormal number of chromosomes (aneuploidy) -- a unique characteristic of cancer cells that researchers have known about for decades -- could become a weak ...

Biologists believe they are one step closer to a long-held goal of making a cheap, widely available plant a source for energy and fuel, meaning one of the next big weapons in the battle against climate change may be able to trace its roots to the side of a Texas highway.

Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin, HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and other institutions have published a complex genome analysis of switchgrass, a promising biofuel crop.

The team tied different genes to better performance in varying climates across North America, which now gives scientists a road map for breeding ...

A high proportion of survivors of Ebola experienced a resurgence in antibody levels nearly a year after recovery, a new University of Liverpool study has found.

Published today in Nature, the finding hints that hidden reservoirs of virus could exist long after symptoms ease and has implications for monitoring programmes and vaccine strategies.

When a person is infected with Ebola virus, their body produces antibodies to fight the disease. Antibody concentrations peak and then decline slowly over time, providing the body with some degree of immune protection ...