(Press-News.org) A high proportion of survivors of Ebola experienced a resurgence in antibody levels nearly a year after recovery, a new University of Liverpool study has found.

Published today in Nature, the finding hints that hidden reservoirs of virus could exist long after symptoms ease and has implications for monitoring programmes and vaccine strategies.

When a person is infected with Ebola virus, their body produces antibodies to fight the disease. Antibody concentrations peak and then decline slowly over time, providing the body with some degree of immune protection over the infection. However, little is known about the antibody response over prolonged time periods.

Researchers from the University's Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences tracked antibodies in a cohort of survivors of Ebola virus disease from the 2014-2016 Sierra Leone outbreak for up to 500 days after recovery from their infection. As expected, antibody levels dropped away slowly after the acute phase of recovery, but then unexpectedly increased rapidly once more around 200 days later, only to decline thereafter. This particular pattern was observed in over half of participants with longitudinal data.

Although there was no detectable Ebola virus in the participants' plasma taken around the time of asymptomatic antibody resurgence, the study indicates that the Ebola virus may be able to persist inside the bodies of many recovered patients for long periods of time. 'Hiding' inside immunologically privileged sites, such as the eyes, central nervous system or testes, the virus may then start to replicate spontaneously, prompting the renewed antibody response.

With this in mind, the researchers suggest that long-term monitoring of survivors is warranted, and that repeat immunisation with vaccines should be considered to boost and maintain protective antibody responses in survivors.

The work was led by Dr Georgios Pollakis, Professor Bill Paxton and Professor Calum Semple at the University of Liverpool and Dr Janet Scott, now at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research.

Research collaborators included experts from Public Health England, the National Safe Blood Service and the 34-Military Hospital, in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Corresponding author and study lead Dr Georgios Pollakis, Senior Lecturer at the University of Liverpool, said: "Our finding that many survivors experienced a resurgence in antibodies, which could not be explained by re-infection or vaccination, was surprising and demonstrates a need for continued monitoring of these patients."

Lead Investigator Professor William Paxton, Professor of Virology at the University of Liverpool, added: "Viruses throw up many surprises, but this high frequency of antibody re-stimulation was not something we expected to find, and indicates that vaccination of Ebola survivors should be considered to keep immunity high and suppress further viral activity. Furthermore, the findings will also help us to better understand the immune system."

Trial Clinical Lead Dr Janet Scott, Clinical Lecturer in Infectious Diseases at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, said: "Evidence of Ebola virus antigen driving an immune response hundreds of days after apparent recovery from Ebola virus disease offers a mechanism that could be driving Post Ebola Syndrome. The clinical science community should now increase efforts to better understand, treat and support Ebola survivors."

Chief Investigator Professor Calum Semple, Professor of Outbreak Medicine at the University of Liverpool commented: "This phenomenon is likely to have occurred in all populations of people who have survived Ebola virus infection in past years. Our description of this biological phenomenon should not be taken to indicate yet more problems for Ebola disease survivors, rather a better understanding of their problems. It is very important to emphasise that no Ebola virus transmission events were observed in this cohort."

The Liverpool team is now using a similar research approach to track antibodies in COVID-19 survivors.

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the University of Liverpool, Wellcome Trust, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Public Health England, and the NHS Blood and Transplant.

Researchers have discovered a novel and druggable insulin inhibitory receptor, named inceptor. The latest study from Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen, the Technical University of Munich and the German Center for Diabetes Research is a significant milestone for diabetes research as the scientific community celebrates 100 years of insulin and 50 years of insulin receptor discovery. The blocking of inceptor function leads to an increased sensitisation of the insulin signaling pathway in pancreatic beta cells. This might allow protection and regeneration of beta cells for diabetes remission.

Diabetes mellitus is a complex disease characterized by the loss or dysfunction of insulin-producing beta cells in the islets of Langerhans, ...

Linking molecular components through amide bonds is one of the most important reactions in research and the chemical industry. In the journal Angewandte Chemie, scientists have now introduced a new type of reaction for making amide bonds. Called an ASHA ligation, this reaction is fast, efficient, works under mild aqueous conditions, and is broadly applicable.

Amide bonds are the bond between a carbonyl carbon (C=O) and an organic nitrogen atom. It is amide bonds that link individual amino acids together into proteins and bind monomers into polyamide plastics like perlon ...

Researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) and the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston have discovered what may be the Achilles' heel of the coronavirus, a finding that may help close the door on COVID-19 and possibly head off future pandemics.

The coronavirus is an RNA virus that has, in its enzymatic toolkit, a "proofreading" exoribonuclease, called nsp14-ExoN, which can correct errors in the RNA sequence that occur during replication, when copies of the virus are generated.

Using cutting-edge technologies and novel bioinformatics approaches, the researchers discovered that this ExoN also regulates the rate of recombination, the ability of the coronavirus ...

Reaching zero net emissions of carbon dioxide from energy and industry by 2050 can be accomplished by rebuilding U.S. energy infrastructure to run primarily on renewable energy, at a net cost of about $1 per person per day, according to new research published by the Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), the University of San Francisco (USF), and the consulting firm Evolved Energy Research.

The researchers created a detailed model of the entire U.S. energy and industrial system to produce the first detailed, peer-reviewed study of how to achieve carbon-neutrality by 2050. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world must reach zero net CO2 ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Culture, civic-mindedness and privacy concerns influence how willing people are to share personal location information to help stem the transmission of COVID-19 in their communities, a new study finds. Such sharing includes giving public health authorities access to their geographic information via data gathered from phone calls, mobile apps, credit card purchases, wristband trackers or other technologies.

Reported in the International Journal of Geo-Information, the study will help public health officials better tailor their COVID-19 mitigation strategies to specific cultural contexts, the ...

Climate change mitigation is about more than just CO2. So-called "short-lived climate-forcing pollutants" such as soot, methane, and tropospheric ozone all have harmful effects. Climate policy should be guided by a clearer understanding of their differentiated impacts.

It is common practice in climate policy to bundle the climate warming pollutants together and express their total effects in terms of "CO2 equivalence". This 'equivalence' is based on a comparison of climate effects on a 100-year timescale. This approach is problematic, as IASS scientist Kathleen ...

In a new article published in the scientific journal Communications Chemistry, a research group at Uppsala University show, using computer simulations, that ions do not always behave as expected. In their research on molten salts, they were able to see that, in some cases, the ions in the salt mixture they were studying affect one another so much that they may even move in the "wrong" direction - that is, towards an electrode with the same charge.

Research on the next-generation batteries is under way in numerous academic disciplines. Researchers at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Uppsala University have developed and studied a model for alkali halides, of which ordinary table salt (sodium chloride) is the best-known example. If these ...

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute, the UCL Cancer Institute, and the Cancer Research UK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence have identified genetic changes in tumours which could be used to predict if immunotherapy drugs would be effective in individual patients.

Immunotherapies have led to huge progress treating certain types of cancer, but only a subset of patients respond, and hence a challenge for doctors and researchers is understanding why they work in some people and not others, and predicting who will respond well to treatment.

In their paper, published in Cell today (27 January), the scientists looked for genetic and gene expression changes in tumours in over 1,000 patients being treated with checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy which stops cancer cells ...

Health authorities should develop targeted health messages for vaping product and e-liquid packaging to encourage smokers to switch from cigarettes to e-cigarettes and to prevent non-smokers from taking up vaping, a researcher at the University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand says.

Professor Janet Hoek, a Co-Director of the University's ASPIRE 2025 Research Centre has led new research analysing the impact of on-package messaging on e-liquids.

The research team found messages presenting electronic nicotine delivery systems as a lower risk alternative to smoking could encourage about a third of smokers to trial them. On the other hand, messages about the ...

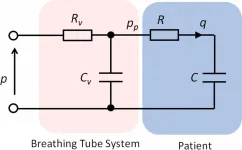

As Covid-19 continues to put pressure on healthcare providers around the world, engineers at the University of Bath have published a mathematical model that could help clinicians to safely allow two people to share a single ventilator.

Members of Bath's Centre for Therapeutic Innovation and Centre for Power Transmission and Motion Control have published a first-of-its-kind research paper on dual-patient ventilation (DPV), following work which began during the first wave of the virus in March 2020.

Professor Richie Gill, Co-Vice Chair of the Centre ...