(Press-News.org) Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute, the UCL Cancer Institute, and the Cancer Research UK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence have identified genetic changes in tumours which could be used to predict if immunotherapy drugs would be effective in individual patients.

Immunotherapies have led to huge progress treating certain types of cancer, but only a subset of patients respond, and hence a challenge for doctors and researchers is understanding why they work in some people and not others, and predicting who will respond well to treatment.

In their paper, published in Cell today (27 January), the scientists looked for genetic and gene expression changes in tumours in over 1,000 patients being treated with checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy which stops cancer cells from switching off the body's immune response*.

They found that the total number of genetic mutations which are present in every cancer cell in a patient was the best predictor for tumour response to immunotherapy. The more mutations present in every tumour cell, the more likely they were to work. In addition, expression of gene CXCL9 was found to be a critical driver of an effective anti-tumour immune response.

The researchers also looked at the cases where checkpoint inhibitors had not been effective. For example, having more copies of a gene called CCND1 was linked to tumours being resistant to checkpoint inhibitors. More research is needed, but the scientists suggest that patients with this mutation in their tumours may benefit more from alternative drug treatment options.

Kevin Litchfield, co-lead author, visiting scientist at the Crick and group leader of the Tumour Immunogenomics and Immunosurveillance lab at UCL says: "This is the largest study of its kind, analysing genetic and gene expression data from across seven types of cancer and over a thousand people.

"It has enabled us to pinpoint the specific genetic factors which determine tumour response to immunotherapy, and combine them into a predictive test to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from therapy. Furthermore, it has improved our biological understanding of how immunotherapy works, which is vital for the design and development of new improved immunotherapeutic drugs."

The researchers are now working with clinical partners in Denmark to see if their test correctly identifies the patients who will or will not respond to checkpoint inhibitors and if this is more accurate than tests currently available.

Charles Swanton, chief clinician at Cancer Research UK and group leader at the Crick and UCL says and a lead author of the study: "Checkpoint inhibitors are really valuable in treating a number of cancers, including skin and lung cancers. But sadly, they do not always work and they can also sometimes cause severe side effects.

"If doctors have an accurate test, that tells them whether these drugs are likely to be effective in each individual patient, they will be able to make more informed treatment decisions. Crucially, they will be able to more quickly look for other options for patients who these drugs are unlikely to help."

Michelle Mitchell, chief executive of Cancer Research UK, says: "One of the main roadblocks preventing us from unleashing the full potential of immunotherapies is that we don't fully understand how these drugs work, or why this type of treatment doesn't benefit everyone. And we still can't fully predict who will respond to these expensive treatments.

"This new research has furthered our understanding around these issues, revealing new drug development tactics and approaches to treatment. It's fantastic to think of a future where we give patients a simple test before they start their immunotherapy to find out if this is the right course of treatment for them. This not only will spare patients from taking needless treatment and enduring serious side effects that might come with it, but it could also save the NHS treatment costs."

The work was partly funded by Cancer Research UK, the Royal Society, the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council and Rosetrees Trust, among others.

INFORMATION:

For further information, contact: press@crick.ac.uk or +44 (0)20 3796 5252

Notes to Editors

Litchfield, K. et al. (2021). Meta-analysis of tumor and T cell intrinsic mechanisms of sensitization to checkpoint inhibition. Cell. DOI number: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.002

* 1,008 patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors were included in the study. The seven tumour type groups are: metastatic urothelial cancer, malignant melanoma, head and neck cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer and breast cancer.

The Francis Crick Institute is a biomedical discovery institute dedicated to understanding the fundamental biology underlying health and disease. Its work is helping to understand why disease develops and to translate discoveries into new ways to prevent, diagnose and treat illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

An independent organisation, its founding partners are the Medical Research Council (MRC), Cancer Research UK, Wellcome, UCL (University College London), Imperial College London and King's College London.

The Crick was formed in 2015, and in 2016 it moved into a brand new state-of-the-art building in central London which brings together 1500 scientists and support staff working collaboratively across disciplines, making it the biggest biomedical research facility under a single roof in Europe.

http://crick.ac.uk/

Health authorities should develop targeted health messages for vaping product and e-liquid packaging to encourage smokers to switch from cigarettes to e-cigarettes and to prevent non-smokers from taking up vaping, a researcher at the University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand says.

Professor Janet Hoek, a Co-Director of the University's ASPIRE 2025 Research Centre has led new research analysing the impact of on-package messaging on e-liquids.

The research team found messages presenting electronic nicotine delivery systems as a lower risk alternative to smoking could encourage about a third of smokers to trial them. On the other hand, messages about the ...

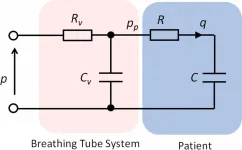

As Covid-19 continues to put pressure on healthcare providers around the world, engineers at the University of Bath have published a mathematical model that could help clinicians to safely allow two people to share a single ventilator.

Members of Bath's Centre for Therapeutic Innovation and Centre for Power Transmission and Motion Control have published a first-of-its-kind research paper on dual-patient ventilation (DPV), following work which began during the first wave of the virus in March 2020.

Professor Richie Gill, Co-Vice Chair of the Centre ...

Scientists have calculated the mass range for Dark Matter - and it's tighter than the science world thought.

Their findings - due to be published in Physics Letters B in March - radically narrow the range of potential masses for Dark Matter particles, and help to focus the search for future Dark Matter-hunters. The University of Sussex researchers used the established fact that gravity acts on Dark Matter just as it acts on the visible universe to work out the lower and upper limits of Dark Matter's mass.

The results show that Dark Matter cannot be either 'ultra-light' or 'super-heavy', as some have theorised, unless an as-yet undiscovered force also acts upon it.

The team used the assumption that the only force acting on Dark Matter is gravity, ...

Although the reputation of Champagne is well established, the history of Champagne wines and vineyards is poorly documented. However, a research team led by scientists from the CNRS and the Université de Montpellier at the Institut des sciences de l'évolution de Montpellier* has just lifted the veil on this history by analysing the archaeological grape seeds from excavations carried out in Troyes and Reims. Dated to between the 1st and 15th centuries AD, the seeds shed light on the evolution of Champagne wine growing, prior to the invention of the famous Champagne, for the first time. According to the researchers, "wild"** ...

Even after accounting for differences in income, education, caregiver support, special education services and parental reports of misbehavior and family conflict, elementary school-age Black children are 3.5 times more likely to be suspended or placed in detention than their white peers, a new study finds.

The results were unsettling even to the researchers themselves, who were familiar with previous research into racial disparities in school discipline. Previous studies primarily used school records, but this study was able to use a nationwide self-reported dataset, with data collected as part of a long-term investigation into how the ...

A newly discovered trace fossil of an ancient burrow has been named after University of Alberta paleontologist Murray Gingras. The fossil, discovered by a former graduate student, has an important role to play in gauging how salty ancient bodies of water were, putting together a clearer picture of our planet's past.

"One could not find a more passionate and influential teacher of science in the classroom, in the field or at a conference," said Ryan King, lead author of the study and now an adjunct professor at Western Colorado University.

"Naming the fossil after Gingras was a straightforward decision since his research focuses ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: Benthic plastic litter is a main source of pollutants in oceans, but how it disperses is largely unknown. This study by Guangfa Zhong and Xiaotong Peng, published today in Geology, presents novel findings on the distribution patterns and dispersion mechanisms of deep-sea plastic waste in a submarined canyon located in the northwestern South China Sea.

Evidence collected from a series of manned submersible dives indicate that the plastic litter items transported and deposited in the canyon are most likely controlled by turbidity currents. Here the plastic litter items are highly heterogeneously distributed: Up to 89% of them occur in a few scours of the canyon.

The plastic items are mostly accumulated in longitudinal litter piles of 2-61 m long, 0.5-8 m wide, ...

JANUARY 26, 2021, NEW YORK - A study led by Ludwig Chicago Co-director Ralph Weichselbaum and Yang-Xin Fu of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center has shown how bacteria in the gut can dull the efficacy of radiotherapy, a treatment received by about half of all cancer patients. Their findings appear in the current issue of the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

"Our study identifies two families of gut bacteria that interfere with radiotherapy in mice and describes the mechanism by which a metabolite they produce--a short chain fatty acid called butyrate--undermines the therapy," said Weichselbaum.

A wide variety of commensal bacteria inhabit ...

Birds play an underrecognized role in spreading tickborne disease due to their capacity for long-distance travel and tendency to split their time in different parts of the world - patterns that are shifting due to climate change. Knowing which bird species are able to infect ticks with pathogens can help scientists predict where tickborne diseases might emerge and pose a health risk to people.

A new study published in the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography used machine learning to identify bird species with the potential to transmit the Lyme disease bacterium (Borrelia burgdorferi) to feeding ticks. The team developed a model that identified birds known to spread Lyme disease with 80% accuracy and flagged 21 new species that should be prioritized for surveillance.

Lead author Daniel ...

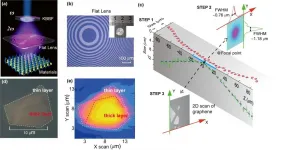

The rapid development of two-dimensional quantum materials, such as twisted bilayer graphene, monolayer copper superconductors, and quantum spin Hall materials, has demonstrated both important scientific implications and promising application potential. To characterize the electronic structure of these materials/devices, angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) is commonly used to measure the energy and momentum of electrons photoemitted from samples illuminated by X-ray or vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) light sources. Although the X-ray-based spatially resolved ARPES has the highest spatial resolution (~100 nm) benefitting from the relatively short wavelength, its energy resolution is typically mediocre (>10 meV), ...