More than just CO2: It's time to tackle short-lived climate-forcing pollutants

2021-01-27

(Press-News.org) Climate change mitigation is about more than just CO2. So-called "short-lived climate-forcing pollutants" such as soot, methane, and tropospheric ozone all have harmful effects. Climate policy should be guided by a clearer understanding of their differentiated impacts.

It is common practice in climate policy to bundle the climate warming pollutants together and express their total effects in terms of "CO2 equivalence". This 'equivalence' is based on a comparison of climate effects on a 100-year timescale. This approach is problematic, as IASS scientist Kathleen Mar explains in a new research paper: "The fact is that climate forcers simply aren't 'equivalent' - their effects on climate and ecosystems are distinct. Short-lived climate forcers have the largest impact on near-term climate whereas CO2 has the largest impact on long-term climate." The use of a 100-year time horizon as the primary basis for evaluating climate effects understates the impacts of short-lived climate-forcing pollutants (SLCPs) and thus undervalues the positive near-term effects that can be achieved by reducing SLCP emissions.

Reducing SLCP emissions benefits climate, human health, and food security

One of the more pernicious qualities of CO2 is that it accumulates in the atmosphere - once it is emitted, it takes a long time for it to be removed. SLCPs, on the other hand, remain in the atmosphere for significantly shorter periods. The atmosphere and climate system react much more quickly to reductions in the emission of these pollutants. This should be a boon for policymakers, Mar argues: "Reducing SLCP emissions would slow near-term climate warming, reduce air pollution, and improve crop yields - all positive benefits that citizens could experience today and in the near future." Studies indicate that a rapid reduction in SLCP emissions could slow the rate of climate change, reducing the risk of triggering dangerous and potentially irreversible climate tipping points and allowing more time for climate adaptation.

Measures to reduce SLCP emissions could be implemented using existing technologies and practices, such as the collection of landfill gas to generate energy. Changes in other sectors will be needed to achieve further reductions. Methane and soot emissions from the agriculture and waste management sectors, for example, have important climate as well as health impacts. Similarly, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are significantly more potent climate forcers than CO2, are still widely used as coolants.

Designing effective climate change mitigation: don't overlook SLCPs

Mar argues that clear communication on the different time horizons relevant for CO2 and SLCP mitigation would help guide climate policy discussions towards more effective outcomes: "To mitigate the most harmful consequences of climate change as a whole, we need to minimize both near-term and long-term climate impacts - and that means reducing SLCPs in parallel to CO2. However, the positive benefits of SLCP mitigation are simply not captured when using the 100-year time horizon as the single benchmark for assessing climate impacts."

Recognizing the broader benefits of SLCP reductions, several countries have stepped up and made SLCP mitigation a central element of their national climate strategies. Chile, Mexico, and Nigeria all include SLCPs in their national commitments under the Paris Agreement. If this type of holistic approach can be expanded and translated into on-the-ground emissions reductions at a global scale, then it will certainly be a win, not only for climate, but for air quality, health, and sustainable development.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-27

In a new article published in the scientific journal Communications Chemistry, a research group at Uppsala University show, using computer simulations, that ions do not always behave as expected. In their research on molten salts, they were able to see that, in some cases, the ions in the salt mixture they were studying affect one another so much that they may even move in the "wrong" direction - that is, towards an electrode with the same charge.

Research on the next-generation batteries is under way in numerous academic disciplines. Researchers at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Uppsala University have developed and studied a model for alkali halides, of which ordinary table salt (sodium chloride) is the best-known example. If these ...

2021-01-27

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute, the UCL Cancer Institute, and the Cancer Research UK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence have identified genetic changes in tumours which could be used to predict if immunotherapy drugs would be effective in individual patients.

Immunotherapies have led to huge progress treating certain types of cancer, but only a subset of patients respond, and hence a challenge for doctors and researchers is understanding why they work in some people and not others, and predicting who will respond well to treatment.

In their paper, published in Cell today (27 January), the scientists looked for genetic and gene expression changes in tumours in over 1,000 patients being treated with checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy which stops cancer cells ...

2021-01-27

Health authorities should develop targeted health messages for vaping product and e-liquid packaging to encourage smokers to switch from cigarettes to e-cigarettes and to prevent non-smokers from taking up vaping, a researcher at the University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand says.

Professor Janet Hoek, a Co-Director of the University's ASPIRE 2025 Research Centre has led new research analysing the impact of on-package messaging on e-liquids.

The research team found messages presenting electronic nicotine delivery systems as a lower risk alternative to smoking could encourage about a third of smokers to trial them. On the other hand, messages about the ...

2021-01-27

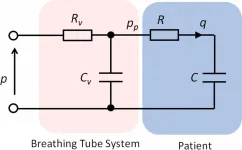

As Covid-19 continues to put pressure on healthcare providers around the world, engineers at the University of Bath have published a mathematical model that could help clinicians to safely allow two people to share a single ventilator.

Members of Bath's Centre for Therapeutic Innovation and Centre for Power Transmission and Motion Control have published a first-of-its-kind research paper on dual-patient ventilation (DPV), following work which began during the first wave of the virus in March 2020.

Professor Richie Gill, Co-Vice Chair of the Centre ...

2021-01-27

Scientists have calculated the mass range for Dark Matter - and it's tighter than the science world thought.

Their findings - due to be published in Physics Letters B in March - radically narrow the range of potential masses for Dark Matter particles, and help to focus the search for future Dark Matter-hunters. The University of Sussex researchers used the established fact that gravity acts on Dark Matter just as it acts on the visible universe to work out the lower and upper limits of Dark Matter's mass.

The results show that Dark Matter cannot be either 'ultra-light' or 'super-heavy', as some have theorised, unless an as-yet undiscovered force also acts upon it.

The team used the assumption that the only force acting on Dark Matter is gravity, ...

2021-01-27

Although the reputation of Champagne is well established, the history of Champagne wines and vineyards is poorly documented. However, a research team led by scientists from the CNRS and the Université de Montpellier at the Institut des sciences de l'évolution de Montpellier* has just lifted the veil on this history by analysing the archaeological grape seeds from excavations carried out in Troyes and Reims. Dated to between the 1st and 15th centuries AD, the seeds shed light on the evolution of Champagne wine growing, prior to the invention of the famous Champagne, for the first time. According to the researchers, "wild"** ...

2021-01-27

Even after accounting for differences in income, education, caregiver support, special education services and parental reports of misbehavior and family conflict, elementary school-age Black children are 3.5 times more likely to be suspended or placed in detention than their white peers, a new study finds.

The results were unsettling even to the researchers themselves, who were familiar with previous research into racial disparities in school discipline. Previous studies primarily used school records, but this study was able to use a nationwide self-reported dataset, with data collected as part of a long-term investigation into how the ...

2021-01-27

A newly discovered trace fossil of an ancient burrow has been named after University of Alberta paleontologist Murray Gingras. The fossil, discovered by a former graduate student, has an important role to play in gauging how salty ancient bodies of water were, putting together a clearer picture of our planet's past.

"One could not find a more passionate and influential teacher of science in the classroom, in the field or at a conference," said Ryan King, lead author of the study and now an adjunct professor at Western Colorado University.

"Naming the fossil after Gingras was a straightforward decision since his research focuses ...

2021-01-27

Boulder, Colo., USA: Benthic plastic litter is a main source of pollutants in oceans, but how it disperses is largely unknown. This study by Guangfa Zhong and Xiaotong Peng, published today in Geology, presents novel findings on the distribution patterns and dispersion mechanisms of deep-sea plastic waste in a submarined canyon located in the northwestern South China Sea.

Evidence collected from a series of manned submersible dives indicate that the plastic litter items transported and deposited in the canyon are most likely controlled by turbidity currents. Here the plastic litter items are highly heterogeneously distributed: Up to 89% of them occur in a few scours of the canyon.

The plastic items are mostly accumulated in longitudinal litter piles of 2-61 m long, 0.5-8 m wide, ...

2021-01-27

JANUARY 26, 2021, NEW YORK - A study led by Ludwig Chicago Co-director Ralph Weichselbaum and Yang-Xin Fu of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center has shown how bacteria in the gut can dull the efficacy of radiotherapy, a treatment received by about half of all cancer patients. Their findings appear in the current issue of the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

"Our study identifies two families of gut bacteria that interfere with radiotherapy in mice and describes the mechanism by which a metabolite they produce--a short chain fatty acid called butyrate--undermines the therapy," said Weichselbaum.

A wide variety of commensal bacteria inhabit ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] More than just CO2: It's time to tackle short-lived climate-forcing pollutants