(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Culture, civic-mindedness and privacy concerns influence how willing people are to share personal location information to help stem the transmission of COVID-19 in their communities, a new study finds. Such sharing includes giving public health authorities access to their geographic information via data gathered from phone calls, mobile apps, credit card purchases, wristband trackers or other technologies.

Reported in the International Journal of Geo-Information, the study will help public health officials better tailor their COVID-19 mitigation strategies to specific cultural contexts, the researchers said.

The scientists assessed survey responses from 306 people living in the United States and South Korea. Participants were recruited through social media and were younger and more highly educated than the general population of those countries. Conducted in late June and early July, the surveys asked participants to rate their privacy concerns, perceptions of social benefit and acceptance of a variety of COVID-19 mitigation efforts that involve collecting geographic data from individuals.

"For each method, we wanted to see how these factors influenced people's willingness to share their data," said Junghwan Kim, a graduate student in geography and geographic information science at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who led the research with Mei-Po Kwan, a geography professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong and Kim's doctoral adviser at the U. of I.

Understanding the factors that influence these decisions is key to designing effective public health campaigns, Kim said. What works in one society may not be viable in a different part of the world.

Participants answered questions about conventional contact tracing, where public health officials call those who test positive for the virus to interview them about where they've been and whom they've potentially exposed. Such methods are time-consuming and inefficient, however, so the researchers also asked participants to rate their attitudes toward public health efforts that collect geolocation information from their phones, track their credit card purchases, ask them to wear a wristband or require that they carry a "travel certificate" demonstrating that they have tested negative for COVID-19.

The surveys also asked subjects to rate how they felt about the public disclosure of location, gender and age information of those who tested positive for the virus, or for the sharing of the public locations they had visited without disclosure of their gender and age.

The team found that people were more concerned about - and less likely to accept - methods that collected more sensitive and private information.

"Not surprisingly, we saw that there is a trade-off relationship between privacy concerns and social benefits," Kim said. "So, there is more acceptance when a person's privacy concern is low and the perceived social benefits are high. We also found that people in South Korea have a significantly higher acceptance of most mitigation efforts than those in the U.S."

This higher acceptance may have to do with South Korea's previous experience with the Middle East respiratory syndrome, which is caused by a much deadlier coronavirus than the one that causes COVID-19, Kwan said. But it likely also is a reflection of South Korea's culture.

"Compared with people in the U.S., South Koreans have a stronger collectivist - rather than individualist - culture," she said. "They also have lower privacy concerns and perceive greater social benefits for COVID-19-mitigation measures."

"The results have important public health policy implications," the researchers wrote. For example, the use of phone-based or wristband GPS tracking "would not be effective in the U.S. and other countries where people's acceptance of these methods is very low." Other approaches, such as random phone calls to monitor people's compliance with quarantine orders or the use of travel certificates that verify a person's COVID-19-negative status, would likely work better in such societies.

INFORMATION:

The National Science Foundation supported this research.

Editor's notes:

To reach Junghwan Kim, email jk11@illinois.edu.

To reach Mei-Po Kwan, email mpk654@gmail.com or mkwan@illinois.edu.

The paper "An examination of people's privacy concerns, perceptions of social benefits, and acceptance of COVID-19 mitigation measures that harness location information: A comparative study of the U.S. and South Korea" is available online and from the U. of I. News Bureau.

Climate change mitigation is about more than just CO2. So-called "short-lived climate-forcing pollutants" such as soot, methane, and tropospheric ozone all have harmful effects. Climate policy should be guided by a clearer understanding of their differentiated impacts.

It is common practice in climate policy to bundle the climate warming pollutants together and express their total effects in terms of "CO2 equivalence". This 'equivalence' is based on a comparison of climate effects on a 100-year timescale. This approach is problematic, as IASS scientist Kathleen ...

In a new article published in the scientific journal Communications Chemistry, a research group at Uppsala University show, using computer simulations, that ions do not always behave as expected. In their research on molten salts, they were able to see that, in some cases, the ions in the salt mixture they were studying affect one another so much that they may even move in the "wrong" direction - that is, towards an electrode with the same charge.

Research on the next-generation batteries is under way in numerous academic disciplines. Researchers at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Uppsala University have developed and studied a model for alkali halides, of which ordinary table salt (sodium chloride) is the best-known example. If these ...

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute, the UCL Cancer Institute, and the Cancer Research UK Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence have identified genetic changes in tumours which could be used to predict if immunotherapy drugs would be effective in individual patients.

Immunotherapies have led to huge progress treating certain types of cancer, but only a subset of patients respond, and hence a challenge for doctors and researchers is understanding why they work in some people and not others, and predicting who will respond well to treatment.

In their paper, published in Cell today (27 January), the scientists looked for genetic and gene expression changes in tumours in over 1,000 patients being treated with checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy which stops cancer cells ...

Health authorities should develop targeted health messages for vaping product and e-liquid packaging to encourage smokers to switch from cigarettes to e-cigarettes and to prevent non-smokers from taking up vaping, a researcher at the University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand says.

Professor Janet Hoek, a Co-Director of the University's ASPIRE 2025 Research Centre has led new research analysing the impact of on-package messaging on e-liquids.

The research team found messages presenting electronic nicotine delivery systems as a lower risk alternative to smoking could encourage about a third of smokers to trial them. On the other hand, messages about the ...

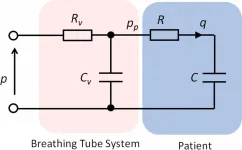

As Covid-19 continues to put pressure on healthcare providers around the world, engineers at the University of Bath have published a mathematical model that could help clinicians to safely allow two people to share a single ventilator.

Members of Bath's Centre for Therapeutic Innovation and Centre for Power Transmission and Motion Control have published a first-of-its-kind research paper on dual-patient ventilation (DPV), following work which began during the first wave of the virus in March 2020.

Professor Richie Gill, Co-Vice Chair of the Centre ...

Scientists have calculated the mass range for Dark Matter - and it's tighter than the science world thought.

Their findings - due to be published in Physics Letters B in March - radically narrow the range of potential masses for Dark Matter particles, and help to focus the search for future Dark Matter-hunters. The University of Sussex researchers used the established fact that gravity acts on Dark Matter just as it acts on the visible universe to work out the lower and upper limits of Dark Matter's mass.

The results show that Dark Matter cannot be either 'ultra-light' or 'super-heavy', as some have theorised, unless an as-yet undiscovered force also acts upon it.

The team used the assumption that the only force acting on Dark Matter is gravity, ...

Although the reputation of Champagne is well established, the history of Champagne wines and vineyards is poorly documented. However, a research team led by scientists from the CNRS and the Université de Montpellier at the Institut des sciences de l'évolution de Montpellier* has just lifted the veil on this history by analysing the archaeological grape seeds from excavations carried out in Troyes and Reims. Dated to between the 1st and 15th centuries AD, the seeds shed light on the evolution of Champagne wine growing, prior to the invention of the famous Champagne, for the first time. According to the researchers, "wild"** ...

Even after accounting for differences in income, education, caregiver support, special education services and parental reports of misbehavior and family conflict, elementary school-age Black children are 3.5 times more likely to be suspended or placed in detention than their white peers, a new study finds.

The results were unsettling even to the researchers themselves, who were familiar with previous research into racial disparities in school discipline. Previous studies primarily used school records, but this study was able to use a nationwide self-reported dataset, with data collected as part of a long-term investigation into how the ...

A newly discovered trace fossil of an ancient burrow has been named after University of Alberta paleontologist Murray Gingras. The fossil, discovered by a former graduate student, has an important role to play in gauging how salty ancient bodies of water were, putting together a clearer picture of our planet's past.

"One could not find a more passionate and influential teacher of science in the classroom, in the field or at a conference," said Ryan King, lead author of the study and now an adjunct professor at Western Colorado University.

"Naming the fossil after Gingras was a straightforward decision since his research focuses ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: Benthic plastic litter is a main source of pollutants in oceans, but how it disperses is largely unknown. This study by Guangfa Zhong and Xiaotong Peng, published today in Geology, presents novel findings on the distribution patterns and dispersion mechanisms of deep-sea plastic waste in a submarined canyon located in the northwestern South China Sea.

Evidence collected from a series of manned submersible dives indicate that the plastic litter items transported and deposited in the canyon are most likely controlled by turbidity currents. Here the plastic litter items are highly heterogeneously distributed: Up to 89% of them occur in a few scours of the canyon.

The plastic items are mostly accumulated in longitudinal litter piles of 2-61 m long, 0.5-8 m wide, ...