After hydrogen, helium is the second most abundant element in the universe. Around one-fourth of the atomic nuclei that formed in the first few minutes after the Big Bang were helium nuclei. These consist of four building blocks: two protons and two neutrons. For fundamental physics, it is crucial to know the properties of the helium nucleus, among other things to understand the processes in other atomic nuclei that are heavier than helium. "The helium nucleus is a very fundamental nucleus, which could be described as magical," says Aldo Antognini, a physicist at PSI and ETH Zurich. His colleague and co-author Randolf Pohl from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany adds: "Our previous knowledge about the helium nucleus comes from experiments with electrons. At PSI, however, we have for the first time developed a new type of measurement method that allows much better accuracy."

With this, the international research collaboration succeeded in determining the size of the helium nucleus around five times more precisely than was possible in previous measurements. The group is publishing its results today in the renowned scientific journal Nature. According to their findings, the so-called mean charge radius of the helium nucleus is 1.67824 femtometers (there are 1 quadrillion femtometers in 1 meter).

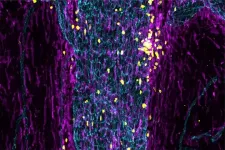

"The idea behind our experiments is simple," explains Antognini. Normally two negatively charged electrons orbit the positively charged helium nucleus. "We don't work with normal atoms, but with exotic atoms in which both electrons have been replaced by a single muon," says the physicist. The muon is considered to be the electron's heavier brother; it resembles it, but it's around 200 times heavier. A muon is much more strongly bound to the atomic nucleus than an electron and encircles it in much narrower orbits. Compared to electrons, a muon is much more likely to stay in the nucleus itself. "So with muonic helium, we can draw conclusions about the structure of the atomic nucleus and measure its properties," Antognini explains.

Slow muons, complicated laser system

The muons are produced at PSI using a particle accelerator. The specialty of the facility: generating muons with low energy. These particles are slow and can be stopped in the apparatus for experiments. This is the only way researchers can form the exotic atoms in which a muon throws an electron out of its orbit and replaces it. Fast muons, in contrast, would fly right through the apparatus. The PSI system delivers more low-energy muons than all other comparable systems worldwide. "That is why the experiment with muonic helium can only be carried out here," says Franz Kottmann, who for 40 years has been pressing ahead with the necessary preliminary studies and technical developments for this experiment.

The muons hit a small chamber filled with helium gas. If the conditions are right, muonic helium is created, where the muon is in an energy state in which it often stays in the atomic nucleus. "Now the second important component for the experiment comes into play: the laser system," Pohl explains. The complicated system shoots a laser pulse at the helium gas. If the laser light has the right frequency, it excites the muon and advances it to a higher energy state, in which its path is practically always outside the nucleus. When it falls from this to the ground state, it emits X-rays. Detectors register these X-ray signals.

In the experiment, the laser frequency is varied until a large number of X-ray signals arrive. Physicists then speak of the so-called resonance frequency. With its help, then, the difference between the two energetic states of the muon in the atom can be determined. According to theory, the measured energy difference depends on how large the atomic nucleus is. Hence, using the theoretical equation, the radius can be determined from the measured resonance. This data analysis was carried out in Randolf Pohl's group in Mainz.

Proton radius mystery is fading away

The researchers at PSI had already measured the radius of the proton in the same way in 2010. At that time, their value did not match that obtained by other measurement methods. There was talk of a proton radius puzzle, and some speculated that a new physics might lie behind it in the form of a previously unknown interaction between the muon and the proton. This time there is no contradiction between the new, more precise value and the measurements with other methods. "This makes the explanation of the results with physics beyond the standard model more improbable," says Kottmann. In addition, in recent years the value of the proton radius determined by means of other methods has been approaching the precise number from PSI. "The proton radius puzzle still exists, but it is slowly fading away," says Kottmann.

"Our measurement can be used in different ways," says Julian Krauth, first author of the study: "The radius of the helium nucleus is an important touchstone for nuclear physics." Atomic nuclei are held together by the so-called strong interaction, one of the four fundamental forces in physics. With the theory of strong interaction, known as quantum chromodynamics, physicists would like to be able to predict the radius of the helium nucleus and other light atomic nuclei with a few protons and neutrons. The extremely precisely measured value for the radius of the helium nucleus puts these predictions to the test. This also makes it possible to test new theoretical models of the nuclear structure and to understand atomic nuclei even better.

The measurements on muonic helium can also be compared with experiments using normal helium atoms and ions. In experiments on these, too, energy transitions can be triggered and measured with laser systems - here, though, with electrons instead of muons. Measurements on electronic helium are under way right now. By comparing the results of the two measurements, one can draw conclusions about fundamental natural constants such as the Rydberg constant, which plays an important role in quantum mechanics.

A collaboration with a long tradition

While the measurement of the proton radius was successful only after protracted experiments, the helium nucleus experiment worked right away. "We were lucky that everything went smoothly," says Antognini, "because with our laser system we are at the limit of the technology, and something could easily break down."

"It will be even more difficult with our new project," adds Karsten Schuhmann from ETH Zurich. "Here we are now addressing the magnetic radius of the proton. And for this the laser pulses have to be ten times more energetic!"

INFORMATION:

The current finding is the result of 20 years of proven collaboration among internationally renowned institutes including PSI, ETH Zurich, the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics in Garching near Munich, the Institut für Strahlwerkzeuge at the University of Stuttgart, and the PRISMA + Cluster of Excellence at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, as well the Kastler-Brossel Laboratory and CNRS in Paris, the Universities of Coimbra and Lisbon in Portugal, and the National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan. The work was funded by the European Research Council, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the German Research Foundation, among others.

Text: Barbara Vonarburg

Images are available to download at https://www.psi.ch/en/node/43551?access-token=ABkP3URn3xtSog6m

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2100 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 400 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research).

Further information

"Protons - smaller than we thought" - Text from 8 July 2010: http://psi.ch/2MHn

Contact

Dr. Aldo Antognini

Labor für Teilchenphysik

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

&

Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics

ETH Zurich, Otto-Stern-Weg 5, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 46 14, e-mail: aldo.antognini@psi.ch [German, English]

Dr. Franz Kottmann

Labor für Teilchenphysik

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

&

Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics

ETH Zurich, Otto-Stern-Weg 5, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 79273 16 39, e-mail: franz.kottmann@psi.ch [German, English]

Dr. Julian J. Krauth

LaserLaB, Faculty of Sciences

Quantum Metrology and Laser Applications

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

De Boelelaan 1081, 1081HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Telephone: +31 20 5987438, e-mail: j.krauth@vu.nl [German, English, Dutch]

Prof. Dr. Randolf Pohl

Institut für Physik

Johannes Gutenberg Universität, 55128 Mainz, Germany

Telephone: +49 171 41 70 752, e-mail: pohl@uni-mainz.de [German, English]

Original publication

The alpha particle charge radius from laser spectroscopy of the muonic helium-4 ion

Julian J. Krauth et al., Nature, 27.01.2021

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03183-1