Human activity caused the long-term growth of greenhouse gas methane

Emissions from the oil and gas sectors, coal mining and ruminant farming drive methane growth over the past three decades

2021-01-29

(Press-News.org) Methane (CH4) is the second most important greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide (CO2). Its concentration in the atmosphere has increased more than twice since the preindustrial era due to enhanced emissions from human activities. While the global warming potential of CH4 is 86 times as large as that of CO2 over 20 years, it stays in the atmosphere for about 10 years, much shorter than more than centuries of CO2. It is therefore expected that emission controlling of CH4 can benefit for relatively short time period toward the Paris Agreement target to limit the global warming well below 2 degrees.

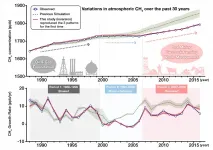

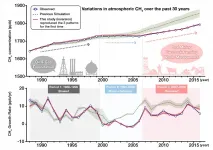

A study by an international team, published in Journal of Meteorological Society of Japan, provides a robust set of explanations about the processes and emission sectors that led to the hitherto unexplained behaviors of CH4 in the atmosphere. The growth rate (annual increase) of CH4 in the atmosphere varied dramatically over the past 30 years with three distinct phases, namely, the slowed (1988-1998), quasi-stationary (1999-2006) and renewed (2007-2016) growth periods (Fig. 1). No scientific consensus is however reached on the causes of such CH4 growth rate variability. The team, led by Naveen Chandra of National Institute for Environmental Studies, combined analyses of emission inventories, inverse modeling with an atmospheric chemistry-transport model, the global surface/aircraft/satellite observations to address the important problem.

They show that reductions in emissions from Europe and Russia since 1988, particularly from oil-gas exploitation and enteric fermentation, led to the slowed CH4 growth rates in the 1990s (Fig. 2), where reduced emissions from natural wetlands due the effects of Mount Pinatubo eruption and frequent El Niño also played roles. This period was followed by the quasi-stationary state of CH4 growth in the early 2000s. CH4 resumed growth from 2007, which were attributed to increases in emissions from coal mining mainly in China and intensification of livestock (ruminant) farming and waste management in Tropical South America, North-central Africa, South and Southeast Asia. While the emission increase from coal mining in China has stalled in the post-2010 period, the emissions from oil and gas sector from North America has increased (Fig. 2). There is no evidence of emission enhancement due to climate warming, including the boreal regions, during our analysis period.

These findings highlight key sectors (energy, livestock and waste) for effective emission reduction strategies toward climate change mitigation. Tracking the location and source type is critically important for developing mitigation strategies and the implementation the Paris Agreement. The study also underlines need of more atmospheric observations with space and time density higher than the present.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-29

New research from the University of Sheffield has found being overweight is an additional burden on brain health and it may exacerbate Alzheimer's disease.

The pioneering multimodal neuroimaging study revealed obesity may contribute toward neural tissue vulnerability, whilst maintaining a healthy weight in mild Alzheimer's disease dementia could help to preserve brain structure.

The findings, published in The Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports, also highlight the impact being overweight in mid-life could have on brain health in older age.

Lead author of the study, Professor Annalena Venneri from the University of Sheffield's Neuroscience Institute and NIHR Sheffield Biomedical Research Centre, ...

2021-01-29

Four million UK patients could benefit annually from genetic testing before being prescribed common medicines, according to new research from the University of East Anglia (UEA) in collaboration with Boots UK and Leiden University (Netherlands).

Researchers looked through 2019 NHS dispensing data across the UK to see how many patients are started on new prescriptions each year that could be potentially optimised by genetic testing.

They studied 56 medicines, including antidepressants, antibiotics, stomach ulcer treatments and painkillers where there are known drug-gene interactions.

And they found that in more than one in five occasions (21.1 ...

2021-01-29

An interdisciplinary team of the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) used an innovative imaging technique for a better understanding of motor deficits in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). The researchers were able to follow the escape behaviour of normal and disease zebrafish models, in 3D. Their results have recently been published in Optica, the flagship journal of the Optical Society (OSA).

Professor Jinyang Liang, expert in ultra-fast imaging and biophotonics, joined an effort with Professor Kessen Patten, specialist in genetics and neurodegenerative diseases. The two groups were able to track the position of ...

2021-01-29

New research from the University of Iowa and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center demonstrates that offspring can be protected from the effects of prenatal stress by administering a neuroprotective compound during pregnancy.

Working in a mouse model, Rachel Schroeder, a student in the UI Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Neuroscience, drew a connection between the work of her two mentors, Hanna Stevens, MD, PhD, UI associate professor of psychiatry and Ida P. Haller Chair of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Andrew A. Pieper, MD, PhD, a former UI faculty member, now Morley-Mather Chair of Neuropsychiatry at Case Western Reserve ...

2021-01-29

-- Experts call for policy reform to improve ethnic equity of socioeconomic opportunity, service provision, and health outcomes. They also call for long-term studies to investigate how structural and institutional racism generate these ethnic inequalities in health.

In 15 out of 17 minority ethnic groups, health-related quality of life in older age (over 55 year-olds) was worse on average for either men, women, or both, than for White British people according to an observational study published in The Lancet Public Health journal.

In five of those groups - Bangladeshi, Pakistani, ...

2021-01-29

Peer-reviewed / Simulation or Modelling / People

A new modelling study has estimated that from 2000 to 2030 vaccination against 10 major pathogens - including measles, rotavirus, HPV and hepatitis B - will have prevented 69 million deaths in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The study estimated that, as a result of vaccination programmes, those born in 2019 will experience 72% lower mortality from the 10 diseases over their lifetime than if there was no immunisation.

The greatest impact of vaccination was estimated to occur in children under five - mortality from the 10 diseases in ...

2021-01-28

Cities are not all the same, or at least their evolution isn't, according to new research from the University of Colorado Boulder.

These findings, out this week in Nature Communications Earth and Environment and Earth System Science Data, buck the historical view that most cities in the United States developed in similar ways. Using a century's worth of urban spatial data, the researchers found a long history of urban size (how big a place is) "decoupling" from urban form (the shape and structure of a city), leading to cities not all evolving the same--or even close.

The researchers hope that by providing this look at the past with this unique data set, they'll be able to glimpse the future, including the impact of population growth on cities or ...

2021-01-28

Boulder, Colo., USA: For most of Earth's history, life was limited to the microscopic realm, with bacteria occupying nearly every possible niche. Life is generally thought to have evolved in some of the most extreme environments, like hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean or hot springs that still simmer in Yellowstone. Much of what we know about the evolution of life comes from the rock record, which preserves rare fossils of bacteria from billions of years ago. But that record is steeped in controversy, with each new discovery (rightfully) critiqued, questioned, and analyzed from every angle. Even then, uncertainty ...

2021-01-28

Scientists are opening new windows into understanding more about the constantly shifting evolutionary arms race between viruses and the hosts they seek to infect. Host organisms and pathogens are in a perennial chess match to exploit each other's weaknesses.

Such research holds tantalizing clues for human health since the immune system is on constant alert to deploy counter measures against new viral attacks. But unleashing too much of a defensive response can lead to self-inflicted tissue damage and disease.

A new study published in the journal eLife by biologists at the University ...

2021-01-28

Scientists have created a new way to detect the proteins that make up the pandemic coronavirus, as well as antibodies against it. They designed protein-based biosensors that glow when mixed with components of the virus or specific COVID-19 antibodies. This breakthrough could enable faster and more widespread testing in the near future. The research appears in Nature.

To diagnose coronavirus infection today, most medical laboratories rely on a technique called RT-PCR, which amplifies genetic material from the virus so that it can be seen. This technique requires specialized staff and equipment. It also consumes lab supplies ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Human activity caused the long-term growth of greenhouse gas methane

Emissions from the oil and gas sectors, coal mining and ruminant farming drive methane growth over the past three decades