(Press-News.org) Boulder, Colo., USA: For most of Earth's history, life was limited to the microscopic realm, with bacteria occupying nearly every possible niche. Life is generally thought to have evolved in some of the most extreme environments, like hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean or hot springs that still simmer in Yellowstone. Much of what we know about the evolution of life comes from the rock record, which preserves rare fossils of bacteria from billions of years ago. But that record is steeped in controversy, with each new discovery (rightfully) critiqued, questioned, and analyzed from every angle. Even then, uncertainty in whether a purported fossil is a trace of life can persist, and the field is plagued by "false positives" of early life. To understand evolution on our planet--and to help find signs of life on others--scientists have to be able to tell the difference.

New experiments by geobiologists Julie Cosmidis, Christine Nims, and their colleagues, published today in Geology, could help settle arguments over which microfossils are signs of early life and which are not. They have shown that fossilized spheres and filaments--two common bacterial shapes--made of organic carbon (typically associated with life) can form abiotically (in the absence of living organisms) and might even be easier to preserve than bacteria.

"One big problem is that the fossils are a very simple morphology, and there are lots of non-biological processes that can reproduce them," Cosmidis says. "If you find a full skeleton of a dinosaur, it's a very complex structure that's impossible for a chemical process to reproduce." It's much harder to have that certainty with fossilized microbes.

Their work was spurred by an accidental discovery a few years back, with which both Cosmidis and Nims were involved while working in Alexis Templeton's lab. While mixing organic carbon and sulfide, they noticed that spheres and filaments were forming and assumed they were the result of bacterial activity. But on closer inspection, Cosmidis quickly realized they were formed abiotically. "Very early, we noticed that these things looked a lot like bacteria, both chemically and morphologically," she says.

"They start just looking like a residue at the bottom of the experimental vessel," researcher Christine Nims says, "but under the microscope, you could see these beautiful structures that looked microbial. And they formed in these very sterile conditions, so these stunning features essentially came out of nothing. It was really exciting work."

"We thought, 'What if they could form in a natural environment? What if they could be preserved in rocks?'" Cosmidis says. "We had to try that, to see if they can be fossilized."

Nims set about running the new experiments, testing to see if these abiotic structures, which they called biomorphs, could be fossilized, like a bacterium would be. By adding biomorphs to a silica solution, they aimed to recreate the formation of chert, a silica-rich rock that commonly preserves early microfossils. For weeks, she would carefully track the small-scale 'fossilization' progress under a microscope. They found not only that they could be fossilized, but also that these abiotic shapes were much easier to preserve than bacterial remains. The abiotic 'fossils,' structures composed of organic carbon and sulfur, were more resilient and less likely to flatten out than their fragile biological counterparts.

"Microbes don't have bones," Cosmidis explains. "They don't have skins or skeletons. They're just squishy organic matter. So to preserve them, you have to have very specific conditions"--like low rates of photosynthesis and rapid sediment deposition--"so it's kind of rare when that happens."

On one level, their discovery complicates things: knowing that these shapes can be formed without life and preserved more easily than bacteria casts doubt, generally, on our record of early life. But for a while, geobiologists have known better than to rely solely on morphology to analyze potential microfossils. They bring in chemistry, too.

The "organic envelopes" Nims created in the lab were formed in a high-sulfur environment, replicating conditions on early Earth (and hot springs today). Pyrite, or "fool's gold," is an iron-sulfide mineral that would likely have formed in such conditions, so its presence could be used as a beacon for potentially problematic microfossils. "If you look at ancient rocks that contain what we think are microfossils, they very often also contain pyrite," Cosmidis says. "For me, that should be a red flag: 'Let's be more careful here.' It's not like we are doomed to never be able to tell what the real microfossils are. We just have to get better at it."

INFORMATION:

FEATURED ARTICLE

Organic biomorphs may be better preserved than microorganisms in early Earth sediments

Christine Nims; Julia Lafond; Julien Alleon; Alexis S. Templeton; Julie Cosmidis

Author contact:

Julie Cosmidis,

julie.cosmidis@earth.ox.ac.uk

Paper URL:

https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article/doi/10.1130/G48152.1/594307/Organic-biomorphs-may-be-better-preserved-than

GEOLOGY articles are online at http://geology.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent. Representatives of the media may obtain complimentary articles by contacting Kea Giles at the e-mail address above. Please discuss articles of interest with the authors before publishing stories on their work, and please make reference to GEOLOGY in articles published. Non-media requests for articles may be directed to GSA Sales and Service, gsaservice@geosociety.org.

https://www.geosociety.org

Scientists are opening new windows into understanding more about the constantly shifting evolutionary arms race between viruses and the hosts they seek to infect. Host organisms and pathogens are in a perennial chess match to exploit each other's weaknesses.

Such research holds tantalizing clues for human health since the immune system is on constant alert to deploy counter measures against new viral attacks. But unleashing too much of a defensive response can lead to self-inflicted tissue damage and disease.

A new study published in the journal eLife by biologists at the University ...

Scientists have created a new way to detect the proteins that make up the pandemic coronavirus, as well as antibodies against it. They designed protein-based biosensors that glow when mixed with components of the virus or specific COVID-19 antibodies. This breakthrough could enable faster and more widespread testing in the near future. The research appears in Nature.

To diagnose coronavirus infection today, most medical laboratories rely on a technique called RT-PCR, which amplifies genetic material from the virus so that it can be seen. This technique requires specialized staff and equipment. It also consumes lab supplies ...

Housing instability and homelessness are widely understood to have an impact on health, and certain housing problems have been linked to specific childhood health conditions, such as mold with asthma. But it has not been clear how overall housing quality may affect children--especially those who are at risk from other social determinants of health such as food insecurity or poverty.

A new nationally representative study in the Journal of Child Health Care, led by researchers at Nationwide Children's Hospital, has found poor-quality housing is independently associated with poorer pediatric health, ...

As states and municipalities begin to roll out mass vaccination campaigns, some people have dared to ask: When will it be safe to resume "normal" activities again? For those in most parts of the United States, the risk of COVID-19 infection remains extremely high.

People now have access to better real-time information about infection rates and transmission at the county or city level, but they still need a framework to help them decide what is safe to do. Social distancing and shutting businesses have reduced the number of cases, but there is mounting pressure to reopen businesses and classrooms.

Life is likely to continue in this limbo for some time. A new model co-authored by ...

A University of Otago study explored factors which influence Americans' levels of concern over climate change, providing discussion on how those factors could impact mitigation efforts.

A key thread of the research examined the ability of people to visualize the future. Results showed that while 74 per cent of respondents were concerned about climate change, only 29 per cent discussed lower carbon options when asked to describe travel in the year 2050.

"This suggests actively envisioning a sustainable future was less prevalent than climate change concern. So while the majority were concerned, ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- People who do not accept inequality are more likely to negatively evaluate companies that have committed wrongdoings than people who do accept inequality, and this response varies by culture, according to researchers at Penn State. The team also found that companies can improve their standing with consumers when they offer sincere apologies and remedies for the harm they caused to victims.

"Some prominent examples of company moral transgressions include Nike's and Apple's questionable labor practices in developing countries, BP's oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico and Volkswagen's emissions scandal," said Felix Xu, graduate student in marketing at Penn State.

In their paper, which published on Jan. 22 in the Journal of Consumer Research, the team ...

Thermoelectric materials, which can generate an electric voltage in the presence of a temperature difference, are currently an area of intense research; thermoelectric energy harvesting technology is among our best shots at greatly reducing the use of fossil fuels and helping prevent a worldwide energy crisis. However, there are various types of thermoelectric mechanisms, some of which are less understood despite recent efforts. A recent study from scientists in Korea aims to fill one such gap in knowledge. Read on to understand how!

One of these mechanisms mentioned earlier is the spin Seebeck effect (SSE), which was discovered in 2008 by a research team led by Professor Eiji Saitoh from Tokyo University, Japan. The SSE is a phenomenon in which ...

DALLAS - Jan. 28, 2021 - Simulation can be a viable way to quickly evaluate and refine new medical guidelines and educate hospital staff in new procedures, a recent study from UT Southwestern's Department of Pediatrics shows. The findings, published recently in the journal Pediatric Quality and Safety and originally shaped around new COVID-19-related pediatric resuscitation procedures at UTSW and Children's Health, could eventually be used to help implement other types of guidelines at medical centers nationwide.

For decades, U.S. hospitals have used the same standard procedures ...

"King Solomon made for himself the carriage; he made it of wood from Lebanon. Its posts he made of silver, its base of gold. Its seat was upholstered with purple, its interior inlaid with love." (Song of Songs 3:9-10)

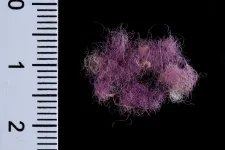

For the first time, rare evidence has been found of fabric dyed with royal purple dating from the time of King David and King Solomon.

While examining the colored textiles from Timna Valley - an ancient copper production district in southern Israel - in a study that has lasted several years, the researchers were surprised to find remnants of woven fabric, a tassel and fibers of wool dyed with royal purple. Direct radiocarbon ...

(For Immediate Release--Singapore--January 28, 2021)-- In the phase II CodeBreak 100 trial, sotorasib provided durable clinical benefit with a favorable safety profile in patients with pretreated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and who harbor KRAS p.G12C mutations, validating CodeBreak 100's phase I results, according to research presented today at the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Outcome in patients with advanced NSCLC on second- or third-line therapies is poor, with a response rate of less than 20% and median progression-free survival of fewer than four months. Approximately 13% of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harbor KRAS p.G12C mutations.

Sotorasib is a first-in-class small molecule that specifically ...